Report on the National Archives of Ireland Census Online

Project: Part 3, Aftermath

Background

This is the third and probably final one of a series

of voluntary reports on the National Archives of Ireland census online

project. Starting in 2005 and finishing in 2011, the National

Archives of Ireland, working with Library and Archives Canada and later

via subcontractors AEL Data of India, placed

online searchable and digitised images first of the Irish Census

of 1911 followed by that of 1901 (website www.census.nationalarchives.ie).

This is work which assuredly needed to be done, but it is questionable

if it was done in the right way by the right people and at minimum cost

to the public purse. As observations on the numbers of errors and

omissions in the online censuses grew, it was conceded by the National

Archives that there were

problems, but it was claimed that they were not severe and would be

attended to in due course. Although the service was free to access

online,

Arts Minister Jimmy Deenihan, responding to a question from Deputy

Catherine Murphy, informed the Dáil on 22 May 2012 that the

total cost to the state of the online census project was €4.6 million,

or €3.64 million net when the VAT tax at 21% paid back to the state was

deducted. Clearly responding to concerns about errors, Minister

Deenihan stated in relation to the 1911 Census that following

'independent statistical analysis, supplemented with scrutiny by a

genealogist expert in Irish names', the 'average level of accuracy was

found to be 99.21%' (Dáil Answers, http://debates.oireachtas.ie/dail/2012/05/22/00253.asp, accessed 14 June 2013).

Accuracy Levels

The writer noted that this claimed accuracy level

was at variance with the findings of the two previous reports in this

series, with sample error rates of 3-14% discovered. However, my

samples were

admittedly small, so a larger sample was clearly needed and in due

course was found. A Freedom of Information application for records

relating to the online

census project was made to the National Archives in 2009 but the

response was slow and partial, so that an appeal was made to the

Information

Commissioner. Among the last batches of records released in May 2012 on

foot of this expensive and time-consuming application and appeals

process was a set of 54 Excel files listing thousands of corrections to

the 1911

Census for areas of Dublin City and County only, which were

commissioned from

members of the Association of Professional Genealogists in Ireland. I

freely admit that due to the voluntary nature of the present

investigation and the demands of other work, it is only now possible to

report on analysis of this substantial body of corrections, which be it

noted would be publicly unknown had it not been for the FOI mechanism.

The

misreadings of surnames in this list were found to be of the usual

variety, clearly

indicating unfamiliarity with Irish names on the part of the

transcribers, examples including Bennbotton for Ramsbottom, Senehaw for

Lenehan, O’Longhlan for O’Loughlan, Meseal for Mescal, Haltin for

Halpin, Tarker for Tasker, Carsen for Cassen, Don? for Donohue,

Faunon for Hannon, Gorgory for Gregory, Tuile for Tuite, Bandergast for

Prendergast, Pardon for Purdon, Land for Lane, Havanagh for Kavanagh,

and - this one is a personal favourite obviously indicating a Canadian

hunch that the famed native American leader had Irish relatives -

Tecumseh for Tennant. Again, had the writer's advice been taken,

transcribers of Irish census data would have been tutored in the forms

of Irish surnames before they got to work, and he would have been

available to do this at budget cost and at a distance via Internet

connections rather than insisting on jetting out to Canada, for

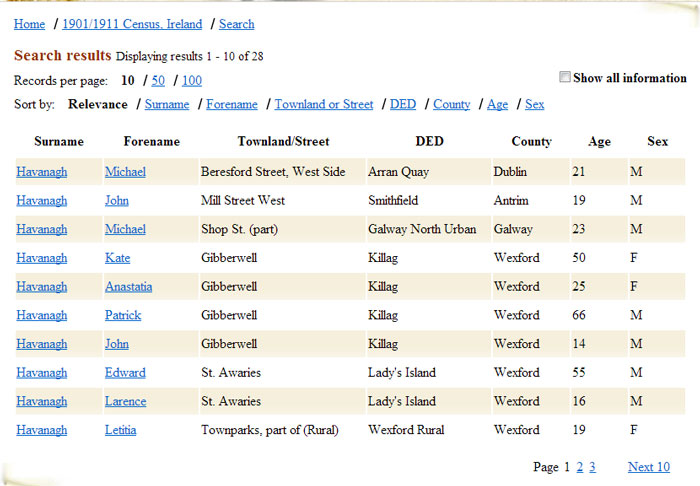

example. The following multiple misreadings of the surname Kavanagh as

'Havanagh' in the 1911 Census online could only have been perpetrated

by individuals with little knowledge of or training in the forms of

Irish surnames.

But what is most striking about the errors in these commissioned lists is their sheer volume, some 32,000 entries, the great bulk of them remaining uncorrected on the National Archives website. A number of errors relating to placenames are also included, which also require attention, but the writer is dealing mainly with surnames in the present series of reports. A large number of other uncorrected name errors submitted by users are stored in an area of the Archives website, and the excuse for failure to deal with this issue has been 'lack of funds', nothwithstanding the above mentioned millions of public money spent on the project. The National Archives has recently announced that it has started to correct these notified errors in the online censuses, claiming to have dealt with 12,600 submissions to date, but this is clearly only the tip of an iceberg (http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/about/user_corrections.html, accessed 14 June 2013). There follows a summary of the 1911 Dublin Census files analysed by the commissioned professional genealogists, giving approximate numbers of errors and indicating whether or not significant corrections have yet been made.

Summary of Dublin 1911 Census errors compiled for National Archives of Ireland by APGI (FOI release on appeal)

Nr Main DEDs, Approx total errors, Corrections made (Yes/No)

1 Clontarf, Drumondra 370 Yes

2 Glasnevin 290 Yes

3 Rathmines & Rathgar 360 Yes

4 Blackrock, Glasnevin, Howth 490 No

5 Rathmines & Rathgar 360 Yes

6 Drumcondra 400 Yes

7 Glasnevin 450 Yes

8 Rathmines & Rathgar 1070 No

9 Palmerstown, New Kilmainham 620 No

10 Balbriggan, Kingstown 260 No

11 Swords East 80 No

12 Trinity Ward 870 No

13 [Kingstown] 280 No

14 Inn’s Quay 660 No

15 Holywood 10 No

16 Ballybrack, Blackrock,

Blanchardstown, Clondalkin, Clonsilla,

Donnybrook 300 No

17 Dalkey 260 No

18 Dundrum 280 No

19 Finglas 100 No

20 Holmpatrick 30 No

21 Kingstown 1 200 No

22 North City 640 No

23 Pembroke East 710 No

24 Inn’s Quay, Kinsaley, Mansion

House 1050 No

25 Coolock 100 No

26 Clontarf

West 170 No

27 Coolock 60 No

28 Killiney 180 No

29 Castleknock 470 No

30 Rathcoole,

Rush, Terenure, North City 830 No

31 Inns

Quay, Newcastle 980 No

32 Rotunda 1100 No

33 Rathmines

& Rathgar East 1210 No

34 Usher’s

Quay 1500 No

35 Merchant’s

Quay 1740 No

36 Fitzwilliam 1190 No

37 Kingstown 570 No

38 Garristown 30 No

39 Glencullen 80 No

40 Lucan 190 No

41 Lusk 100 No

42 South

City, Skerries, Swords 310 No

43 Wood

Quay 1760 No

44 South

Dock 1150 No

45 Arran

Quay 890 No

46 Malahide,

Rathmichael, Royal Exchange 2540 No

47 Mountjoy 730 No

48 Pembroke

West 1500 No Hallormann Halloran

49 Saggart,

Tallagh (sic), Stillorgan 440 No

50 Mountjoy 530 No

51 Arran

Quay 270 No

52 Arran

Quay 490 No

53 Mountjoy 340 No

54 Arran

Quay 250 No

Grand total of errors 32,000 approx

On the basis of this particular commissioned survey alone, the statement that the accuracy rate of the National Archives online census project is 99.21% deserves little credence. The population of Ireland in 1911 was approximately 4.4 million, so an inaccuracy rate of 0.79% would give a total of approximately 35,000 errors for the thirty-two counties of Ireland, while the above figure of approximately 32,000 errors relates to Dublin City and County alone! Minister Deenihan undoubtedly passed on information on the accuracy rate of the census project to the Dáil in good faith, but it is clear that he has been provided with misinformation and the parliamentary record really should be corrected.

Library and Archives Canada

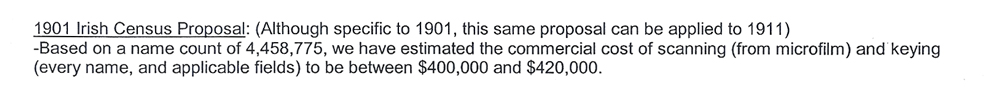

The choice of Library and Archives Canada as the National Archives of Ireland's digitisation partner might seem on the face of it to be a good one, given its resources and experience. However, for some time Library and Archives Canada has been the subject of criticism concerning the way it has been managed, culminating in the resignation of its head Daniel Caron in May 2013 following an expenses scandal (Ottawa Citizen, 15 May 2013, http://www.ottawacitizen.com/news/Library+head+Daniel+Caron+resigns+expenses+found/8391614/story.html, accessed 23 May 2013). Controversy has continued following the revelation that Library and Archives Canada 'has entered a hush-hush deal with a private high-tech consortium that would hand over exclusive rights to publicly owned books and artifacts for 10 years' (Ottawa Citizen, 12 June 2013, http://www.ottawacitizen.com/news/Library+Archives+Canada+private+deal+would+take+millions+documents+public+domain/8511544/story.html, accessed 15 June 2013). It has long puzzled the present writer that the 'considerable amount of digitised and contextual material from their collections' which Library and Archives Canada was supposed to provide as part of the census project (draft agreement December 2005, FOI release) is not in evidence on the National Archives site, which contains only a small amount of such background material provided by the Archives itself. It is also not clear why Library and Archives Canada was not contractually required to correct deficiencies in its work and how exactly the project was passed on for completion to AEL Data (who to be fair put more order on it). Before the census digitisation project was fully under way, in or about June 2005 the Comptroller and Auditor General asked a series of pertinent questions about the choice of Library and Archives Canada, to which the National Archives replied with assurances that this was the most cost-effective option and that alternatives had been considered (FOI release). The €3.64 million net cost of the census project, of which it is not clear what portion was paid to Library and Archives Canada, seems extraordinarily high to the present writer, who would have thought a figure in the region of €1 million and certainly not more than €2 million would have been more appropriate. It can now be revealed via another belated FOI release that a representative of a leading commercial genealogical service provider, whose name is withheld for reasons of commercial confidentialilty, furnished the National Archives with the following estimate of the costs of an Irish census project in March 2004:

At a US dollar-Euro exchange rate of 1.23 in March 2004, this would give a figure of €325,000-342,000 for the 1901 Census, while doubling these amounts to take account of the 1911 Census would produce an estimated grand total of €650,000-684,000. Add in a figure for compiling contextual material and creating an online infrastructure and you would be left with a total project cost in the region of €1-1.25 million. Remarkably, the particular firm just mentioned and, separately, the Mormon Church through the Genealogical Society of Utah both offered to digitise the censuses at no cost to the Irish state, but were aparently rebuffed. Finally, the actual images now online were scanned not from the original census returns but from microfilms prepared by the Mormons, which would have tended to reduce the cost of the exercise. How on earth could the National Archives of Ireland online census project have cost the state a massive €3.64 million net or nearly three times the above rational estimate?

Conclusion

One correspondent writing recently to a newspaper on the

subject of National Archives funding has asked pertinently, 'Should the

National Archives strive to correct the records already released to the

public, before embarking on further releases which may contain similar

inaccurate detail, to the frustration of all concerned?' (Letters, Irish Times, 23 May 2013, http://www.irishtimes.com/debate/letters/national-archives-funding-1.1403128,

accessed 23 May 2013). To a large extent this debate has now become

academic, in that the high expenditure days of the 'Celtic

Tiger' have now gone, although there is still a hankering in

certain quarters after expensive 'special projects' like the flawed

online census one under examination. As the writer advised should be

the case in earlier reports,

and as others too have recommended, projects to digitise public

records for genealogical and other purposes are now being led by

commercial and voluntary organistations, such as Findmypast, Ancestry

and FamilySearch, who interestingly sometimes now co-operate on

such projects. Examples of major projects concluded in recent times

under this model include Irish prison registers, petty sessions court

records, tithe books, landed estates court catalogues and will

calendars (see FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Findmypast.ie, http://www.findmypast.ie). Realistically, the 1901 and 1911 Censuses should be

redatabased by the aforementioned groups, as it would be just too expensive

to

correct all the errors in the National Archives version, errors which

if

outside advice had been heeded, would have been avoided in most cases.

The 1926 Census, whose release before the due date of 2027 is currently being called for but is by means guaranteed, should

in the first instance be processed and catalogued by National Archives

staff and then allowed

to be digitised by one or a combination of the voluntary and commercial groups.

Rather than seeking to waste more scarce public funds on projects

beyond its capabililties and indeed remit, the National Archives should

concentrate on using available resources to maintain services to the

public and to tend to the records in its care as best it can. The

Archives should bring cataloguing of records up to date and

adapt to the new era of digital archives, concentrating on licencing and overseeing as

opposed to directly managing digitisation projects, ensuring

that users have ready and free access to online digitised

records on its premises, eschewing exclusive or nontransparent deals

and extracting

the maximum royalty payments from commercial groups. It is now eight

years since the writer endeavoured to contribute positively to the

National Archives census online project, but at all stages he has been

treated with frank disregard and indeed contempt by senior personnel,

on which unfortunate note the present series of reports is brought to

a close.

Sean J Murphy MA

Centre for Irish Genealogical and Historical Studies

14 June 2013