The National |

||||||||||||||||

The following section is intended to provide some contextual information concerning refugees and asylum seekers in Ireland. Glossary of Key TermsRefugeeThe term 'Refugee' can be used in two senses in relation to Ireland. The first is the broad generic definition of someone who has left their country through persecution, or fear of persecution, which is given international recognition through the UN definition and the second is the use of 'refugee' to describe someone who has been given refugee status. Generic definitionThe commonly accepted definition of a refugee is contained in the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (as amended by the New York Protocol of 1967). This places an obligation on the States which have ratified the Convention (including Ireland) to determine the presence of a refugee and to provide the necessary and appropriate protection. Any person who, owing to a well founded fear of being persecuted on the grounds of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it Refugee StatusThe second use of the term refugee is in the context of 'refugee status' which is granted by the Irish government to those people who they consider fulfil the requirements of the definition of 1951 Convention, as interpreted by domestic legislation and procedures. Refugee Status grants all the benefits of citizenship except for the right to vote. 1 There are two main categories of refugees in Ireland, Programme Refugees and Convention Refugees. There is also a third, smaller category 'humanitarian leave to remain' which is granted in exceptional circumstances at the discretion of the Minister of Justice, Equality and Law Reform. For a summary of the legal framework concerning refugees and asylum seekers see Appendix 1 Programme RefugeeA programme (or quota) refugee is a person who has been invited to Ireland on foot of a government decision in response to humanitarian requests from bodies such as the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees). In recent years the majority of Bosnian and Vietnamese refugees have been granted refugee status as programme refugees. Convention RefugeesAn asylum seeker who has been granted refugee status is sometimes referred to as a 'convention refugee' (after the 1951 Geneva Convention). As with Programme Refugees, they are entitled to take up employment and to receive health, education, social welfare, housing and other public services on the same basis as Irish nationals. Asylum SeekerAn asylum seeker is someone who seeks to be recognised as a refugee under the terms of the 1951 Convention and has applied to be recognised as a convention refugee. Humanitarian Leave to remainLeave to Remain is granted at the discretion of the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform to allow on humanitarian grounds a person to remain in the State who does not fully meet the requirements of the 1951 Convention. Asylum seekers with Humanitarian Leave to Remain receive a residence permit which is renewable every year, pending an improvement in the situation in their country of origin. After 5 years they can apply for citizenship. Global and European ContextThe reasons for the existence of refugees and the increase in the number of refugees coming to Ireland seeking asylum in particular can only be understood in a global and European context WorldwideWorldwide, the United Nations estimates that there are approximately 26 million refugees in areas covered by the UN High Commission for Refugees and up to 50 million refugees in total. The breakdown is as follows

There are about 20 million people living outside their own countries and around 30 million who are internally displaced people within their own country. Most refugees are not in refugee camps and most often refugees try to make lives for themselves in neighbouring countries. Only 5% of the world's refugees are in Europe. The UN estimates the number of refugees has doubled since 1984 and that 80% are women and children. Refugees are escaping wars; political and social repression; poverty and environmental problems. EuropeAccording to the UN high Commission for Refugees, the last decade has witnessed a growing tendency for governments and judicial systems, including those in Europe, to interpret the criteria for refugee status in an increasingly restrictive manner. Part of the reason for this is the increase in political support for anti immigration tendencies and parties. The mid 1980's saw a growth in the support of far right tendencies in countries including France, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, and Switzerland. The agenda of these tendencies has focused in on issues such as migration, political asylum, and opposition to cultural diversity. While many of these parties are not actually in government, the growth in their support has influenced more mainstream political parties to advocate more restrictive criteria for those seeking asylum. Since 1987 the acceptance rate for asylum applications in the EU has fallen from 50% to 10% because of the application of more restrictive criteria. There are also concerns, particularly from non government organisations, about the development of a perceived 'Fortress Europe' and the development of a refusal to address the social, economic and political implications of what Jacques Santer describes as 'a sea of poverty' surrounding the European 'isle of richness'.  It is somewhat ironic that at the same time that internal borders and regulations are relaxing within the European Union, external borders have been tightened in recent years. Some examples of these restrictions include the following:

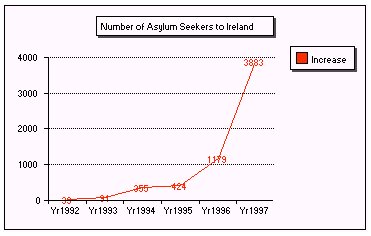

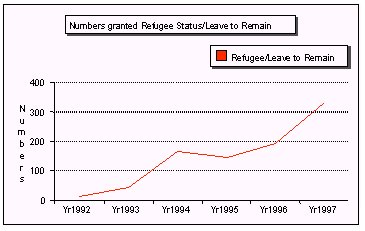

IrelandThe increase in the number of applications from asylum seekers for refugee status to Ireland are illustrated in the following graph and table.  Applications for Refugee Status to Ireland Compared with selected European Countries

These figures show a significant increase in the numbers of people seeking asylum in Ireland over a six year period. However these increases started from a very low base (39 people in 1992) and the total cumulative number (6000) of asylum seekers since 1992 represents only 0.15% of Ireland's population. There has been a number of assertions put forward to explain the increase in the numbers of asylum seekers to Ireland in recent years. One of the most repeated assertions is that the strength of the Irish economy pulling people to Ireland is the most important reason and therefore, by logical conclusion, most asylum seekers are in fact 'bogus' and are in reality economic migrants. On closer analysis, the type of evidence which has been used to support this assertion has been weak. The 'economic migrant' argument is usually supported by the coincidence of the increase in the numbers of asylum seekers with the recent improvement in Ireland's economy and the fact that some people are smuggled into Ireland in an organised way. However, the increase in the numbers of people seeking asylum in Ireland may be less to do with the 'Celtic Tiger' than the harmonising of restrictive practices which makes it increasingly difficult to apply for refugee status in other European countries, resulting in refugees seeking asylum in Ireland. In relation to the smuggling of people into the country; there is little evidence provided to date that this is a widespread practice. Secondly, the method of entry into a country does not determine whether someone is a asylum seeker or not. A further relevant point is that the principal countries of origin for asylum seekers to Ireland in 1997 were Rumania, Congo (the former Zaire), Nigeria, Algeria, Somalia, Angola and Russia. All of these countries have experienced severe political, social and economic upheavals or conflicts in recent years. The number of asylum seekers actually recognised as refugees or granted 'Leave to Remain' by the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform increased from 16 in 1992 to 332 in 1997. A considerable backlog of over 3000 people seeking asylum has now built up in the system and the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform has recently allocated greater resources to process applications more quickly.  Racism

In recent years there has been a growth in the numbers of Black, minority ethnic and non EU nationals living in areas such as Ennis and in particular inner city Dublin. This is consistent with the history of most ethnic groups in Ireland who have tended to live in particular areas including particular parts of a town or city. The reasons for this concentration in particular areas are multifaceted and are related to 'pull' factors such as closeness to transport terminals; the availability of accommodation; proximity to services; proximity to economic opportunities and the wish of living closely with other people of the same ethnic or national origin, including family and friends. It is also related to push factors, such as the inability to afford housing elsewhere, fear or the experience of isolation and racism and the unfamiliarity with other areas, or lack of a tradition of going to such areas. This is not a new phenomenon and would be familiar to many Irish emigrants to Britain and the United States. It is also not a new phenomenon in Ireland, for example, the Huguenots fleeing religious and civil persecution in France in the late 17th century gravitated towards the Liberties area of Dublin. The South Circular Road in Dublin has been traditionally associated with the Jewish and Muslim communities. Some existing communities have felt threatened by the apparent change in the ethnic profile of their area. This has resulted in an increased number of incidents of racially motivated violence and harassment. There are, however, many local community groups which are working closely with refugee and asylum seeker groups to address racism and to promote their inclusion and integration into the communities in which they live. Programme refugees have also experienced racism. In the survey carried out by the Refugee Resettlement Research Project on the needs of Programme Refugees, 32% of Vietnamese participants and 9.5% of Bosnian participants stated they had experienced some form of racism which ranged from verbal to physical attacks. Women refugee and asylum seekers"Reflecting on some of the huge losses incurred by refugee women alerts us to the need for the development of good and sensitive services to meet their needs" (Comlámh, 1997) To date much of the debate around asylum and racism has failed to focus on the experience of women, which often differs significantly from men. This will have clear implications for the key elements in an effective response to the needs of refugees and asylum seekers, including gender specific community development strategies. The UNHCR has produced Guidelines on the Protection of Refugee Women (1991) and gender guidelines have been introduced into asylum procedures in Australia; Canada and the United States. The Irish 1996 Refugee Act recognises the specificity of the experience of women by including 'gender' as a defining characteristic of persons persecuted as a result of their membership of a particular social group. The reasons for women seeking asylum and their experience in the countries to which they have fled to can vary considerably. Reasons for seeking asylum

The articulation of the need to develop gender specific policies towards asylum seekers is at a very early stage. There has to date been no systematic strategies undertaken to identify what these needs are in an Irish context. The production of leaflets in country of origin languages and the availability of interpreters in hospitals and medical centres and the organisation of information events through refugee groups have been put forward as an initial response to meeting some of these needs. It is likely that the key elements of an effective approach to meeting the needs of women asylum seekers will involve a two pronged approach of developing both gender specific strategies and developing a gender dimension to mainstream actions. RomaUnless they have a clean start. A new start. Unless of course, the Irish people import rumours and prejudice. Unless we greet them with the familiar, homegrown innuendo that we show towards the Irish Travelling community' (Sunday Times, August 8, 1998) In August 1998 much attention focused on a small number of Romanians, including Roma (Romanian Gypsies) who arrived in Wexford. This prompted an angry editorial in the 'Wexford People' which among other points, contended that the 'latest influx of asylum seekers has brought public services to breaking point and there is evidence of growing racial tensions'. These contentions were later denied by the Gardai Superintendent in Wexford and the Press Officer from the Health Board - which has responsibility for administering social welfare supports to asylum seekers. Articles in other newspapers and recent research reports provide a very different picture to that provided by the Wexford Leader and identify the reasons why the Roma have sought asylum in countries such as Ireland including:

As well as facing the range of difficulties and barriers experienced by most asylum seekers to Ireland, including language; access to education and health care; securing adequate accommodation; the Roma have added barriers to overcome. In particular they potentially face the burden of a compounded form of exclusion - as refugees and as gypsies/Travellers.

Page Contents: Main Page |

About Us |

News |

Travellers |

Refugees |

Government | ||||||||||||||||

The type of racism most often commented upon are incidents of harassment, racially motived attacks or the expression of racist hatred on the street, through graffiti or in late night radio phone-in programmes. Labelling and scapegoating of groups are also common expressions of racism. In relation to refugees and asylum seekers the most recurring labelling includes the exaggeration of the overall numbers ('floods', 'tides' etc); the stereotyping of refugees as 'scroungers' who are unwilling to work or labelling of refugees as people likely to be involved in criminal activity and the linked assertion that most are 'bogus' and are in reality economic migrants.

The type of racism most often commented upon are incidents of harassment, racially motived attacks or the expression of racist hatred on the street, through graffiti or in late night radio phone-in programmes. Labelling and scapegoating of groups are also common expressions of racism. In relation to refugees and asylum seekers the most recurring labelling includes the exaggeration of the overall numbers ('floods', 'tides' etc); the stereotyping of refugees as 'scroungers' who are unwilling to work or labelling of refugees as people likely to be involved in criminal activity and the linked assertion that most are 'bogus' and are in reality economic migrants.