| Irish Chiefs Back to Homepage |

MacCarthy Versus Horak 1997-98

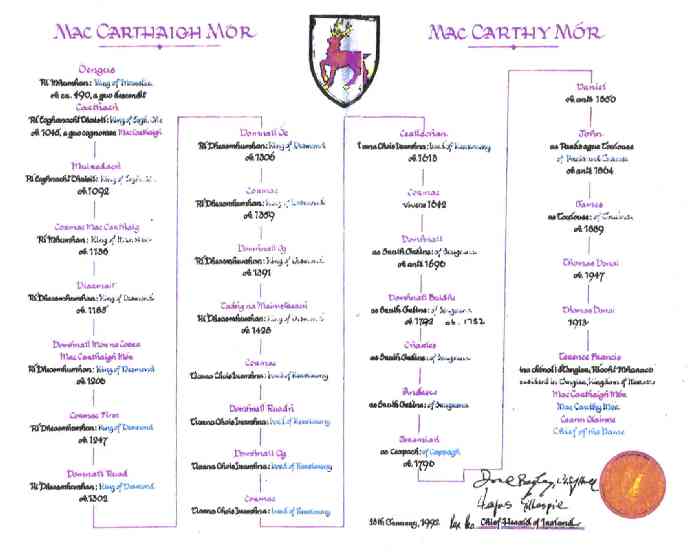

Certificate

recognising Terence MacCarthy as a Gaelic chief, signed by the

then Chief Herald of Ireland

and his acting deputy, issued 1992, entered in evidence in MacCarthy versus

Horak 1997-98

and nullified 1999

Background

Ten years ago there commenced the

remarkable court case MacCarthy versus Horak, a key episode in the Mac

Carthy Mór affair. It will be recalled that since the 1980s

Terence MacCarthy of Belfast had lain claim to the chiefship of the

MacCarthys of Munster, and in 1992 was recognised as Mac Carthy

Mór via a certificate bearing the signatures of both the then

Chief Herald of Ireland and his then acting deputy (see illustration

above). Yet despite this approval by Irish state officials there

were increasing questions

concerning MacCarthy's title and royal ancestry, and by 1997 a rival

claimant had

appeared, in the person of Barry Trant McCarthy of Wiltshire. For

reasons which will be explained, Terence MacCarthy chose Casale

Monferrato, a moderately sized city or town in Piedmont, north-west

Italy, as the place in which to have recourse to law in an effort to

allay emerging doubts about his status and to silence detractors.

The decision to take a legal case

was stated to have been provoked by one Dr Marco Horak, who, it was

alleged, had both publicly and privately denied firstly

MacCarthy’s right to bear the more elaborate coat of arms of the

‘Eóghanacht Royal House of Munster’, as opposed to

the version registered by the Chief Herald of Ireland, and secondly

that he could bestow feudal titles without the consent of the Chief

Herald of Ireland. On 15 July 1997 it was stated that MacCarthy wrote

to Horak, warning him to desist from making such claims, which warning

was claimed to have gone unheeded.

Italy is a republic, and while

its constitution does not recognise titles, it has been claimed that

its legal system

nonetheless provides a method for the trial of issues relating to coats

of arms, taking account of pedigrees, titles and orders as

well. However anomalous it might seem, it would appear that a mechanism

(Lodo Arbitrale) was available to

establish in Casale Monferrato an Arbitral Court of Peers, whose

members were required to be of suitable rank and qualification. This

civil court of arbitration was intended to hear matters in dispute

between parties, and to render a judgment which would be binding

on both. MacCarthy and Horak agreed to bring their dispute before this

court, and the case commenced on 4 December 1997.

Marco Horak was described as a

member of the Union of Nobility of Italy, a Knight of the Constantinian

Order of Saint George, an expert scholar and author of numerous works

on heraldry, genealogy and nobiliary rights. MacCarthy and Horak agreed

to the appointment of three judges, all of noble status, namely,

Dr Roberto Messina, again a Constantinian Knight and expert scholar,

who presided, together with the Marchioness Dr Bianca Maria Rusconi, a

Constantinian Dame and expert scholar, and Dr Riccardo Pinotti, a

Constantinian Knight, official of the Republic of San Marino, and of

course expert scholar.

It is notable that the judges and

the defendant were associates of Dr Pier Felice degli

Uberti, sometimes styled Count of Cavaglià, Chairman of the

International Commission for Orders of Chivalry, and indeed Dr Pinotti

was his father-in-law. The International Commission had been

established at the Fifth International Congress of Genealogical and

Heraldic Sciences at Stockholm in 1960, and was chaired for many years

by the Scottish chief, heraldist and nobiliary law expert Lieutenant

Colonel Robert Gayre of Gayre and Nigg. Gayre had aroused

considerable opposition by having the Commission recognise the revived

Order of St Lazarus, and the body thereafter became heavily Lazarite in

composition. Through the Secretary General of the Commission,

Lieutenant Colonel Patrick O’Kelly de Conejera, Terence MacCarthy

became acquainted with Gayre and in 1984 succeeded in having his

controversial Niadh Nask order added to the register. More than that,

after Gayre’s death MacCarthy came to dominate the Commission, so

that by 1998 he was President, with O’Kelly de Conejera

Vice-President, degli Uberti Chairman, Charles McKerrell of Hillhouse

Deputy Chairman, and Dr Maria Loredana Pinotti Secretary General. It is

clear therefore that Casale Monferrato was chosen as the location for

the trial of the case largely as a result of Terence MacCarthy’s

International Commission connections.

The

First Verdict

The Arbitral Court reportedly

convened at Casale Monferrato on 9 December 1997 in order to

consider the pleas and evidences of both parties. The plaintiff

MacCarthy produced a massive quantity of documentation in support of

his case, which totalled some 2,500 pages and included the following:

certificate recognising MacCarthy as Mac Carthy Mór, dated

28 January 1992, signed both by Chief Herald Donal F Begley and his

then acting deputy Fergus Gillespie; a copy of MacCarthy’s Irish

passport in which he was described as ‘The MacCarthy Mór,

Prince of Desmond’; a letter from the Standing Council of Irish

Chiefs and Chieftains confirming that MacCarthy had been a member since

its ‘reconstitution’ in 1991; a certificate issued 19 April

1993 by Cashel Urban District Council confirming that it had granted a

civic reception to MacCarthy; a copy of the manuscript Genealogie de la

Royale et Serenissime Maison de MacCarthy; extracts from Who’s Who in Ireland and Debrett’s People of Today;

copies of Chief Herald Begley’s letters of 18 June and 3 November

1988 confirming there was no objection to MacCarthy’s disposal of

titles; the whole completed with copies of publications by MacCarthy

and his partner Andrew Davison, ‘Count of Clandermond’, and

some other miscellaneous published material.

The Court commenced its review of

the evidence by considering sections 1 and 2 of Article 40.2 of the

Irish Constitution, which declare respectively, ‘Titles of

nobility shall not be conferred by the State’, and ‘No

title of nobility or of honour may be accepted by any citizen except

with the prior approval of the government’. It was noted that

while the Republic of Ireland had chosen to recognise the existence of

Gaelic Royal Houses, under international law a successor state had no

right to alter the status of heads of non-ruling royal houses. It

appeared to the Court that lordships of the Kingdom of Desmond were

listed in a St Leger Tract of 1588 and in the Genealogie de MacCarthy

Manuscript. The Mac Carthy Mór’s ‘prerogatives over

those feudal lordships’ had been recognised by the Chief Herald

in his letter of 16 June 1988. Furthermore, such titles were a form of

‘incorporeal property’, and Article 40.3.2 of the Irish

Constitution guaranteed citizens full enjoyment of their property. The

Chief Herald in his letter of 16 June 1988 had conceded that Mac Carthy

Mór had ‘under our Constitution . . . the right to

beneficial disposal of such property’.

The Court then turned to consider

the arms claimed by MacCarthy, briefly reviewing firstly the history of

heraldry in Ireland and the Anglo-Norman and Gaelic traditions thereof.

It was noted that while as in the case of other Gaelic ruling

families the MacCarthys had only adopted ‘true heraldry’ in

the sixteenth century, the main device of a Red Stag had been

associated with the Eóghanacht Monarchy for centuries. The arms

of Donal Mac Carthy Mór, Earl of Clancare, were recorded in

their basic form as ‘Argent, a stag trippant gules, unguled and

armed or’(meaning, ‘on a silver shield a red stag hooved

and antlered gold’), which was the form of the arms registered by

the Chief Herald. However, there was stated to be evidence from other

sources, and particularly from folio 99 of the Genealogie de MacCarthy

Manuscript, that the shield should be ‘surmounted by the ancient

five-pointed gold crown of the Kingdom of Desmond, surrounded by a

Niadh Nask Collar, and supported by two Angels’, with the motto Lámh Láidir Abú

(‘Strong Arm Forever’). Leading branches of the MacCarthys

in exile in France had borne this more elaborate version of the arms,

and the current Mac Carthy Mór was therefore following the

example of his predecessors in displaying these arms.

The Court further examined the

question of the sovereignty which can be exercised by a deposed prince.

While the rights of commanding and enforcing obedience may be limited,

the Fons Honorum or

prerogative of bestowing titles is maintained complete and may be

transmitted to successors. In the case under examination, the Court

observed that although ‘deprived of the exercise of effective

authority over those territories once included within the Kingdoms of

Munster and Desmond’, the Mac Carthy Mór enjoyed within

his clan ‘what could be considered to be a non-territorial

sovereignty over more than half a million people dispersed throughout

the world who bear his surname’.

The judges Messina, Rusconi and

Pinotti arrived at a verdict on 19 December 1997, which was in favour

of the plaintiff MacCarthy and against the defendant Dr Marco Horak.

The Court declared that MacCarthy was entitled to bear his various

titles, to exercise the prerogative of Fons Honorum, to dispose

according to his own wishes of those Gaelic feudal lordships vested in

the Eóghanacht Royal House of Munster, and to bear the full coat

of arms of the said Royal House. In view of the ‘special

nature’ of the case and the ‘free services’ of the

judges, it was ruled that the expenses of the trial were considered

paid. On 20 December, the verdict or ‘arbitration ruling’

was filed in the Records Office of the Magistrate Court of Casale

Monferrato, and on 12 January 1998 the said Court declared the

arbitration to be final and conferred on it the legal effect of a

judgment.

The

Second Verdict

This was not the end of the

proceedings, for the Arbitral Court at Casale Monferrato had deferred

consideration of other differences between MacCarthy and Dr Marco Horak

until the following year. On 22 June 1998 the Court, presided over by

the same judges Messina, Rusconi and Pinotti, was stated to have

convened again to adjudicate in the matter of the right of Mac Carthy

Mór to surmount the coat of arms of the Niadh Nask or Military

Order of the Golden Chain with the ancient Crown of Munster. Horak was

alleged to have stated on many occasions that there was no historical

evidence of the existence in Gaelic Ireland of knighthood or the Niadh

Nask itself, and that MacCarthy’s conferral of such an Order was

therefore illicit. It was stated that on 30 August 1997 MacCarthy had

written to Horak warning him to desist from these allegations, but

without effect.

Again the plaintiff MacCarthy

produced to the Court voluminous evidences in support of his case,

including the verdict of 19 December 1997; the Chief Herald’s

certificate of 28 January 1992; the Genealogie de MacCarthy Manuscript;

the plaintiff’s Irish passport; the letter from the Standing

Council of Irish Chiefs and Chieftains; the 1996 edition of the Register of the International Commission

for Orders of Chivalry listing the Niadh Nask; South African

letters patent dated 23 March 1983 recording the arms of the Niadh

Nask; documentation recognising the name and arms of the Niadh Nask

issued by government agencies in Canada and the United States of

America; and various publications by MacCarthy, the ‘Count of

Clandermond’ and others.

The Court commenced by

considering whether there was historical evidence for the existence of

knighthood in Gaelic Ireland before the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169.

It was noted that both Selden and Froissart had stated that the Gaelic

Irish had their own distinctive forms of knighthood, and that the

defendant’s assertion to the contrary was based on

ignorance. In relation to historical evidence for the existence

of the Niadh Nask, the Court referred to sources cited in a work

submitted by the plaintiff. Among the sources and authorities cited

were the Annals of Clonmacnoise,

Geoffrey Keating, Comte O’Kelly d’Aghrim, Canon U J Burke,

P W Joyce, whose combined weight allegedly proved that there existed an

ancient Irish order called the Niadh Nask or Knights of the Golden

Collar. Though it was indicated that the reputed founder of the Niadh

Nask, King Muinheamhoin, who reigned about 691 BC, was mythical, the 88

recorded unbroken generations of descent between him and the plaintiff

Mac Carthy Mór were noted by the Court.

The Court then moved to consider

a matter which was apparently not germane to the issues before it, but

which clearly must have been inspired by the recent claim to the title

of Mac Carthy Mór lodged by Barry Trant McCarthy. This was

presented as the ‘hypothetical’ case of a succession

dispute between an incumbent Mac Carthy Mór holding his title by

Tanistry, and a ‘Pretender’ claiming the same title by

right of primogeniture. Such a rival claim, it was asserted, could not

be heard in any court, since Mac Carthy Mór was ‘not

answerable in such a matter to any jurisdiction whatsoever other,

possibly, than his own Derbfine,

or Council of the Princes of the Blood’. If such an hypothetical

Pretender sought recognition from a successor state, ‘the legal

consequences of such an act would amount to treason against his own

dynasty’. Furthermore, it was pointed out that the legal code of

the Republic of Ireland was based on English Common Law, under which

all Gaelic titles had been abolished. The Chief Herald’s

‘administrative procedure’ of granting ‘courtesy

recognition’ to bearers of Gaelic titles was ‘questionable

if not actually illegal’, and certainly gave him no legal

authority to ‘annul their laws of succession’. Accordingly,

the Court held ‘that the only valid laws governing the descent of

the chiefship of the Eóghanacht Royal House of Mac Carthy Mor,

with the Hereditary Headship of the Niadh Nask therein vested, are the

Brehon Laws of Tanistry’. The Court then conducted an historical

review of the descent of the Eóghanacht Crowns of Munster and

Desmond, proving to its own satisfaction that the Brehon Laws of

Tanistry and not primogeniture had been the operative mode of

succession.

After these digressions, the

Court returned to the main matter in hand, the Niadh Nask. The Court

concluded from the evidence presented that such an order had existed

from the remote past without interruption, and stated that it lay

within the Fons Honorum of

the plaintiff MacCarthy ‘to bestow the Niadh Nask as a dynastic

honour’. The Court also noted that the Niadh Nask had been

recognised as ‘an armigerous body corporate’ in the

jurisdictions of South Africa, Canada and the United States of America.

Accordingly, on 19 June 1998 the judges Messina, Rusconi and Pinotti

rejected the plea of the Defendant Horak and once again upheld the

complaints of the Plaintiff MacCarthy, declaring that the Niadh Nask

‘must be considered in international law as a dynastic honour of

the Royal House of Munster’, that the Republic of Ireland had

‘no jurisdiction in any matter determined by Brehon Law’,

and that the plaintiff as chief of the Eóghanacht Royal House

had the right to use the arms of the Niadh Nask, ‘surmounted by

the Ancient Royal Crown of Munster’. As in the first trial, the

costs of the suit were waived. It is not clear whether the second

verdict was filed in the Records Office of the Magistrate Court of

Casale

Monferrato like the first.

Horak does not appear to have

submitted documentation as detailed as MacCarthy’s, and all in

all seems to have been a rather docile or perhaps cowed defendant

throughout the proceedings in both trials. There is no sign of vigorous

questioning of MacCarthy’s evidence on the part of Horak, and in

general the field was left clear for the plaintiff effectively to

dictate the verdicts.

Aftermath

Supporters of MacCarthy were keen

to promulgate the Italian verdicts in his favour, and in November 1998

issued a published account under the title A New Book of Rights (Clonmel,

County Tipperary, 1998), which contained the text of the legal

proceedings and verdicts translated from Italian to English, together

with several essays containing historical and legal commentary. Peter

Berresford Ellis contributed an introduction, in his capacity as

‘Historian to the Royal House of Munster’, wherein he

insisted again that succession to Gaelic titles must be by Brehon Law.

In particular, Ellis claimed that the Casale Monferrato judgements

meant that the primacy of Brehon Law in this regard was now

recognised under international law. John Michael Johnson, an American

military judge and a Niadh Nask, described the first verdict in favour

of Terence MacCarthy as ‘a model of analytical clarity’,

and the second verdict as consolidating ‘the historical,

genealogical and legal framework which underpins the Niadh Nask’.

Captain Mitchell Lee Lathrop,

described as Attorney General of the Niadh Nask, hailed the court

decisions as representing ‘a milestone in clarifying and

harmonising different legal concepts based upon different bodies of

law’. David Victor Brooks, described as Legal Counsel to Mac

Carthy Mór and again a Niadh Nask, rounded on ‘a small,

ill-informed Anglophile and Hibernophobic, Internet-addicted clique of

self-acclaimed experts’ who had attempted ‘to denigrate the

historical status of Irish princes’. The work concluded with an

English translation and the text in Spanish of a certificate of arms

issued to MacCarthy on 8 December 1997 by the Marqués de la

Floresta, Cronista de Armas de Castilla y León, which

specifically cited documents validating his pedigree issued by Chief

Heralds of Ireland. This was preceded by purported observations of one

of the Casale Monferrato judges, Dr Rusconi, who following comment on

the supposed Spanish origins of the Eóghanacht Royal House of

Munster via Milesian descent, allegedly declared that the

Cronista’s certificate constituted a formal act by which the

Crown of Spain, through a certificate issued by a delegated officer,

had ‘recognised the fact that The Mac Carthy Mór, Prince

of Desmond, is the Chief of his Name and Arms and Head of his Royal

House, and possessed of the power of Fons

Honorum’.

When the present writer first

learned of the Casale Monferrato verdicts via Internet reports and the

aforementioned publication, the initial reaction was one of surprise

that an Italian court would presume to make such rulings in favour of

MacCarthy. What would have been the response if a claimant to an

Italian noble title and arms had secured judgments in his favour in an

Irish court? It would be fair to say that the Internet publicity

generated by the case, and in particular online discussions on the

newsgroup rec.heraldry, provided me with the inspiration and indeed

information to commence an in-depth study of the Mac Carthy Mór

affair.

It is of course now clear that

the MacCarthy versus Horak case was completely contrived, a device

which has not been uncommon where a bearer of a questionable title is

seeking to have it validated. Of such cases Enrique Carlos Count

Zeininger de Borja is reported to have written:

In Ireland the Office of the Chief Herald did not react to the

legal proceedings in Casale Monferrato, maintaining a silence on its

role in validating MacCarthy’s claim to chiefship which would

only be broken in the wake of the exposure of the hoax in 1999. To

set the record straight once again, the present writer issued an

independent report on 16 June 1999

exposing the falsity of Terence MacCarthy's claims, and the role of the

Office of the Chief Herald in facilitating same, which was followed by

an exposé in the Irish edition of the Sunday Times on 20 June. The

following month, on 19 July, the then Chief Herald Brendan O Donoghue

announced

that he had nullified MacCarthy's recognition as a chief and

invalidated his confirmation of arms and registered pedigree (taking

time also to bestow gratefully on the present writer the title of

'self-appointed saviour of Irish genealogy').

In February 2004 there was an

admission during a further discussion on rec.heraldry that the Casale

Monferrato case was indeed contrived, but it was claimed that those who

organised and facilitated the proceedings were acting not as

accomplices of MacCarthy but as friends of Dr Horak endeavouring to

protect him from legal ruin, that in effect they were all victims of

MacCarthy’s blackmail (discussion archived at http://groups.google.com).

This explanation bears the merit of plausibility, and invites

acceptance on grounds of charity, but the present writer does not

believe that it tells the whole story. Additionally, the writer was

informed by Dr degli Uberti, now in charge of a reconstituted and

post-MacCarthyite International Commission for Orders of Chivalry, that

the above mentioned article attributed to Dr Rusconi was in fact a

forgery, raising questions as to whether other parts of A New Book of Rights were also

fabricated.

Indeed it is not clear if any

kind of formal court proceedings ever took place in Casale Monferrato,

whether all the participants actually met face to face, and it would

not be unreasonable at this juncture to describe the case MacCarthy

versus Horak as in itself a hoax. Of course it remains a moot point as

to how ethically acceptable it would be under any circumstances to

participate in such a legal sham, which brought no credit at all to the

Italian legal system. Yet some good did come of the preposterous

proceedings in Casale Monferrato in 1997-98, in that in retrospect they

can be seen to have helped trigger Terence MacCarthy’s downfall,

and hopefully they have made it difficult if not impossible for any

other impostor to engineer a similar case in Italy in particular.

I was several times assured that

the verdicts in MacCarthy versus Horak were formally annulled, but

promised documentary confirmation of this claim has not materialised. I

must also admit to disappointment that for some eight years Dr degli

Uberti has left unamended online a charge that I have written about

MacCarthy versus Horak ‘in an incompetent manner’, opining

also that ‘the peoples who attend newsgroups rarely prove their

affirmations by documents and prefer unscientifically expressions and

superficial opinions while avoiding to study the question more

deeply’ (http://www.geocities.com/Paris/Cathedral/4800/IIHG/MCM2.html).

Alas, my main offence is not that I lack the capacity to grasp the

complexities of cases such as that of Mac Carthy Mór, but that I

understand them only too well, and truth is indeed harder to forgive

than lies. While the Office of the Chief Herald was reconstituted in

2005 in the wake of the Mac Carthy Mór scandal, and the second

signatory of Terence MacCarthy's certificate of chiefship promoted to

the post of Chief Herald in 2005, serious questions remain concerning

the office's legal power to grant arms (http://homepage.eircom.net/%7Eseanjmurphy/chiefs/armscrisis.htm). A fully referenced account of MacCarthy versus Horak is to be

found in my book Twilight of the

Chiefs: The MacCarthy Mór Hoax, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004,

pages 87-95. In conclusion, it should be emphasised that MacCarthy

versus Horak was not an authentic law case, its verdicts never had

any legal validity whatsoever and certainly they did not establish any

points of law either nationally or internationally in relation to the

Mac Carthy Mór chiefship, or with regard to pedigrees, arms,

titles and

orders in general.

Sean J Murphy MA

Centre for Irish Genealogical and Historical Studies

12 January 2008, last amended 20 January 2008