Click to view Image Gallery Click to view

Irish Historical Mysteries: A Centenary Report on the

Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels in 1907

Introduction

The theft of the Irish Crown Jewels by a person or persons unknown in 1907

is one of the most famous and puzzling mysteries of Irish history, and has been the

subject of numerous books and articles. (1) The Jewels were worn during functions

of the Order of St Patrick and were entrusted to the care of Ulster King of Arms,

Ireland’s chief herald and genealogist. Many and various are the theories which

have been advanced over the years to explain what happened to the Jewels, with

allegations that they were stolen by insiders, or by Unionist conspirators eager to

derail Home Rule, or by Republican plotters seeking to embarrass the British

government. On the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the issue of the report

of an official commission of investigation into the loss of the Jewels, (2) it might be

worthwhile to revisit the affair.

As an historian, genealogist and heraldist the present writer has taken upon

himself the task of compiling this centenary report, and the following were set as the

terms of reference:

(1) To examine as much as possible of the surviving documentary evidence relating to the theft of the Irish Crown Jewels in 1907.

(2) To review the proceedings of the Viceregal Commission of investigation into the circumstances of the theft of the Jewels which was published in 1908.

(3) To evaluate various theories advanced over the years as to who might have been responsible for the theft, and in the light of the available evidence to try and identify the most likely culprit or culprits.

The Theft of the Jewels

It should be pointed out firstly that the ‘Irish Crown Jewels’ were not the

equivalent of the English Crown Jewels in the Tower of London, but were in fact the

regalia or insignia of the Order of St Patrick. This was a chivalric order founded by

the government in 1783, designed to be the Irish counterpart of the British Order of

the Garter, and equally a source of honour and patronage. The first Grand Master

was the Third Earl Temple, who was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and the prime mover

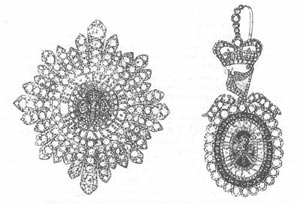

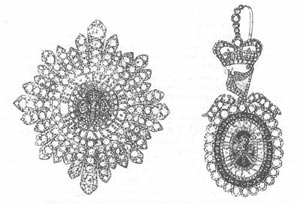

in founding the Order. The Jewels or regalia were presented to the Order by King

William IV in 1831, and are believed to have been made up from diamonds

belonging to Queen Charlotte. The Jewels were crafted by Rundell, Bridge and

Company of London, and consisted of a Star and a Badge composed of rubies,

emeralds and Brazilian diamonds, mounted in silver, which were to be worn by the

Lord Lieutenant as Grand Master on formal occasions. The membership of the

Order was composed of leading peers titled Knights Companions. The Ulster King of

Arms, the state heraldic and genealogical officer in charge of the Office of Arms,

was made responsible for registering the Order’s membership and caring for its

insignia. (3)

The statutes or rules of the Order of St Patrick were revised in 1905, and it

was ordered that the jewelled insignia of the Grand Master and the collars and

badges of the members should be deposited in a steel safe in the strongroom of the

Office of Arms. The Office of Arms was located in Dublin Castle, and in 1903 moved

from the Bermingham Tower to the Bedford Tower. The serving Ulster King of Arms

was Sir Arthur Vicars, who had been appointed in 1893. Other, largely honorary

office-holders under Vicars were Pierce Gun Mahony, Cork Herald, Francis (Frank)

Shackleton, Dublin Herald, and Francis Bennett Goldney, Athlone Pursuivant.

Mahony was a nephew of Vicars, while Shackleton, the brother of the famous

explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, was a housemate of Vicars. After fitting out of the

new premises in the Bedford Tower had been completed, it was found that the

Ratner safe in which the Order’s insignia were to be kept was too large to fit through

the door of the strongroom. By agreement with the Board of Works it was therefore

decided to leave the safe in the Library until a more suitably-sized safe could be

obtained, but this was never done. While seven latch keys to the door of the Office

of Arms were held by Vicars and his staff, there were only two keys to the safe

containing the insignia, both held by Vicars. (4)

The last occasion on which the Jewels were seen in the safe was on 11 June

1907, when Vicars showed them to John Crawford Hodgson, the librarian of the

Duke of Northumberland. On the morning of Wednesday 3 July there was a strange

occurrence, when Mrs Farrell the office cleaner found the entrance door unlocked,

told William Stivey the messenger, who on informing Vicars received the rather

offhand reply, ‘Is that so?’, or ‘Did she?’. On the morning of Saturday 6 July there

was an even more alarming occurrence, when Mrs Farrell found the door of the

strongroom ajar, and on being informed by Stivey, Vicars again replied casually,

taking no further action.

At about 2.15pm on the same day, 6 July, Vicars gave Stivey the key of the

safe and a box containing the collar of a deceased knight, asking him to deposit it in

the safe. This was most unusual, as Stivey had never before held the safe key in his

hand. Stivey found the safe door unlocked and immediately informed Vicars, who

came and opened the safe to find that the Jewels, five Knights’ collars and some

diamonds belonging to Vicars’s mother were all gone. The police were called, and in

the subsequent investigation lock experts established that the safe lock had not

been tampered with, but had been opened with a key. While Mahony was not in the

Office of Arms from April until 4 July, except one day in May, Shackleton and

Goldney appeared not to have visited the premises or indeed been in Ireland

between 11 June and 6 July. (5)

The discovery of the theft of the Jewels caused great concern to government,

and indeed King Edward VII was particularly angered, as he was within days of

visiting Ireland and intended to invest a knight of the Order of St Patrick. Apparently

largely on the King’s insistence, it was decided to reconstitute the Office of Arms and

replace Vicars. Vicars, however, refused to resign, being supported by his

half-brother, Pierce O’Mahony, father of Pierce Gun Mahony and a self-styled Gaelic

Chief titled The O’Mahony. (6) O’Mahony senior became the most prominent figure

in a campaign for a public enquiry which it was hoped would vindicate Vicars.

The Viceregal Commission of Investigation

Lord Aberdeen, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, decided to appoint a Viceregal

Commission of inquiry in January 1908, whose terms of reference were ‘to

investigate the circumstances of the loss of the regalia of the Order of St Patrick’,

and ‘to inquire whether Sir Arthur Vicars exercised due vigilance and proper care as

the custodian thereof’. (7)

The examination of witnesses was led by the Solicitor General, Redmond

Barry. The members of the Commission were Judge James J Shaw, Robert F

Starkie and Chester Jones. The Commission commenced its sittings on 10 January

1908 in the Library of Ulster’s Office, the very room from which the Jewels had been

removed, and would complete its hearings fairly quickly on 16 January. A problem

arose immediately, in that it was found that the Commission was to sit in private and

would not have power to compel the attendance of witnesses or take evidence on

oath. Vicars wanted a sworn public enquiry, and therefore withdrew from the

proceedings with his counsel, so that the Commission had to continue without its

most important witness. However, the Commission was able to use written

statements made by Vicars to the police, as well as oral statements made by him to

the police and various witnesses. (8)

Some twenty-two individuals agreed to give evidence when called. These

included firstly members of the staff of Ulster’s office, including George D Burtchaell,

Vicars’s secretary, the trio of unpaid assistant heralds, Pierce Gun Mahony, Cork

Herald, Francis Shackleton, Dublin Herald, and Francis Bennett Goldney, Athlone

Pursuivant. Then there were various policemen and officials, including M V Harrel,

Assistant Commissioner of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, Superintendent John

Lowe of the same force, Chief Inspector John Kane of Scotland Yard, and Sir

George C V Holmes, Chairman of the Board of Works. Joining Vicars in refusing to

give evidence were Sydney Horlock, his clerk, and Mary Gibbon, the office typist. (9)

Burtchaell was examined on three occasions and his evidence elucidated the

workings of Ulster’s Office, as well as giving the impression that Vicars perhaps was

not as careful as he should have been in his custody of office keys, and that he was

in habit of proudly showing off the Jewels to a wide range of people. Burtchaell also

confirmed that of the three heralds, Goldney had not been in the office since May,

Shackleton since early June, but that Mahony had been present in the period

immediately before the discovery of the loss of the Jewels in July 1908. The

testimony of Peirce Mahony junior was taken at two sittings and was largely taken up

with establishing his role in Ulster’s Office, his access to keys and his attendance at

Ulster’s Office, but was not otherwise very informative.

Goldney was examined at two sessions, and his evidence in contrast was

very lively. The drift of his testimony became evident when Goldney stated that on

one occasion when Vicars was displaying the Jewels to callers there were ‘some

strange gentlemen in the room’. While claiming to have no idea as to who might

have taken the Jewels, Goldney coyly referred to ‘another matter’, which after some

hesitation the Commission decided to enter on the record. This other matter turned

out relate to complicated and strange financial relationships between Vicars,

Shackleton and Goldney. Vicars had guaranteed two bills for Shackleton, which it

was beyond his means to support, and accordingly he persuaded Goldney to take

responsibility, a task which involved dealings with a money lender associated with

Shackleton. This aspect of Goldney’s evidence certainly did not have the effect of

presenting Vicars in a good light.

Of the policemen who gave evidence, Chief Inspector Kane was the most

interesting. Kane stated that he believed that the theft of the Jewels had been

carried out by an insider, and that it had occurred before 5 July. Kane explained the

doors found open in Ulster’s Office as a deliberate device ‘to precipitate an

investigation’. Kane also testified that Vicars and Goldney had stated to him that

they believed Shackleton to have been responsible for the theft, a charge he

rejected emphatically:

I have repeated to Sir Arthur Vicars and his friends over and over again, and I desire to say that now, when they pestered me with not only suggestions, but direct accusations of Mr Shackleton, that they might as well accuse me, so far as the evidence they produced went to justify them. (10)

Unfortunately, Kane’s report on the loss of the Jewels is among the official

documentation now missing, and this might have thrown further light on just why he

was so certain that the man who remains the prime suspect was innocent.

Shackleton was among the final witnesses to give evidence, travelling back to

Dublin from San Remo in Italy for the purpose. Shackleton gave the impression of

being a helpful and composed witness, which of course might not have been the

case had Vicars’s counsel been there to cross-examine him. He candidly outlined

his connection with Vicars, stating that he had made his acquaintance through his

heraldic and genealogical work, that he was a co-tenant with him of a house in

Clonskeagh, that indeed Sir Arthur had guaranteed bills for him when he was in

some temporary financial difficulties. He admitted that he had in the past spoken of

the Jewels as being likely to be stolen, but took every opportunity to claim that the

suspicions against him were groundless. Read into the record was a letter from

Vicars to Shackleton, sent on 25 August 1907 from Goldney’s residence Abbots

Barton in Canterbury, in which Vicars commented:

Now that you evidently know the whereabouts of the Jewels, from what you have said to both Frank [Goldney] and me, I hope that you have told Mr Kane everything calculated to facilitate matters. (11)

Shackleton indicated that this exchange was based on nothing more than his reference to a newspaper report that the Jewels had been recovered, which turned out to be incorrect. In answer to direct questions as to whether he or a confederate had taken the Jewels, Shackleton replied:

I did not take them; I know nothing of their disappearance; I have no suspicion of anybody. . . . . . I had no hand in it, nor do I know anybody that took them, nor have I the least suspicion. (12)

Taking advantage of his social contacts, Shackleton dropped many prominent

names, and referred several times to his poor health and the distance he had

travelled from San Remo to give evidence. At one point Shackleton stated that he

had even been accused of aiding Lord Haddo, Lord Aberdeen’s son, in taking the

Jewels, whereupon the Solicitor General intervened quickly to indicate that he ‘need

not mention that’. (13)

The Viceregal Commission issued its report on 25 January 1908, and the key

finding was as follows:

Having fully investigated all the circumstances connected with the loss of the Regalia of the Order of St Patrick, and having examined and considered carefully the arrangements of the Office of Arms in which the Regalia were deposited, and the provisions made by Sir Arthur Vicars, or under his direction, for their safe keeping, and having regard especially to the inactivity of Sir Arthur Vicars on the occasions immediately preceding the disappearance of the Jewels, when he knew that the Office and the Strong Room had been opened at night by unauthorised persons, we feel bound to report to Your Excellency that, in our opinion, Sir Arthur Vicars did not exercise due vigilance or proper care as the custodian of the Regalia. (14)

While admitting it was not part of their terms of reference, the Commissioners also stated that as Francis Richard Shackleton had been more than once named as the ‘probable or possible author of this great crime’, they though it only due to that gentleman to say that

. . . he appeared to us to be a perfectly truthful and candid witness, and that there was

no evidence whatever before us which would support the suggestion that he was the

person who stole the Jewels. (15)

The Viceregal Commission hearings had in effect been converted into a trial

in absentia of Sir Arthur Vicars, and his own withdrawal together with his counsel

had left the field clear for his accusers. Although the Viceregal Commission’s terms

of reference specified both the circumstances of the loss of the Jewels and the

conduct of Vicars, it would seem that highlighting the latter’s failings took

precedence over trying to establish just who had purloined the Jewels. The

Commission’s findings were couched in terms of allocating most blame for the loss

of the Jewels to Vicars, indeed on making him a scapegoat, and in this the

Commissioners could not really be accused of failing to do what was expected of

them. There can be a level of cynicism attached to official reports, in which while no

palpable untruths are told, certain facts can be manipulated and others ignored in

order to arrive at a predetermined result. While the Commission’s finding that Vicars

was careless in his custody of the Jewels was essentially accurate, the exculpation

of Shackleton seems remarkable when not accompanied by closer analysis of the

alleged exploit of Lord Haddo, or the security failings of other Castle staff, for

example. Another factor explaining the kid gloves with which Frank Shackleton was

treated may have been the status of his brother Sir Ernest as a national hero and

favourite of King Edward VII. Although it would appear that Ernest’s own finances

were in a parlous state due to the expenses of his polar expeditions, he felt obliged

to borrow £1,000 in order to help his brother Frank repay the above mentioned

debts. (16) It would not be unjust to conclude that the Viceregal Commission report

was in essence a whitewash designed to draw a veil over an intensely embarrassing

episode for the establishment and to allocate most of the blame to Vicars.

On 30 January 1908 Vicars was informed that his appointment as Ulster King

of Arms had been terminated, and Captain Nevile Rodwell Wilkinson was appointed

in his place. As the disgruntled Vicars refused to hand over the keys to the Office of

Arms strongroom, Wilkinson found himself obliged to stage another break-in in order

to gain entry! Shackleton too and Goldney were removed, but Pierce Gun Mahony

perhaps unexpectedly was left in place. Pierce Mahony senior responded to the

Commission’s report with an even more robust and public defence of his half-brother

Vicars. In early February 1908 he released to the press copies of his copious

correspondence with members of the Irish administration, in which he alleged that

while officially Vicars was charged only with negligence, graver charges relating to

his character were being circulated in secret. In particular, Mahony alleged that he

had been informed by Lord Aberdeen and the Chief Secretary Augustine Birrell that

Vicars stood accused of introducing into his office ‘a man of very bad character’, and

while the name of the individual was deleted in the press report, it is considered that

this must have been a reference to Frank Shackleton. Mahony and Vicars continued

to press for a full public and judicial enquiry so that the dismissed Ulster could clear

his name. A letter sent to the press by Vicars on 1 February 1908 provided his initial

response to the charges of the Viceregal Commission: he declared that the Board of

Works were responsible for not providing a safe which would fit in the strong room of

his office, and explained his failure to react to the reports of open doors by reference

to his being overwhelmed with work in advance of the royal visit. Government was

unmoved, considering that the matter had been resolved by the report of the

Viceregal Commission and the replacement of Vicars as Ulster. (17)

Shackleton, Goldney and Other Suspects

The Viceregal Commission clearly provided the official view of the Jewels

theft, but a much murkier account of the whole affair found its way into the public

domain in July 1908 via an article in an Irish-American nationalist newspaper the

Gaelic American. Based apparently on information provided by Vicars’s half-brother

Pierce O’Mahony, this article asserted that drunken parties had been held in the

Office of Arms, with an implication of homosexual activity (‘nightly orgies’, ‘unnatural

vice’). It was claimed that Shackleton and a disreputable associate named Captain

Richard Gorges (for some reason disguised as ‘Captain Gaudeons’ in the article),

were responsible for stealing the Jewels, and the two had escaped punishment by

threatening to expose the scandalous conduct in the Castle. The article also alleged

that there had been a secret Dublin Metropolitan Police enquiry operating in parallel

with that of the Commission, which had subjected Shackleton to a less benign

interrogation when he had completed his evidence before the commissioners.

Although the authorities allegedly knew the identities of those who had stolen the

Jewels, they could not secure hard evidence against them or persuade them to

reveal the whereabouts of their booty. In consequence of this, and out of a desire to

avoid further scandal and revelations, it was said that the police contented

themselves merely with ordering Shackleton and Gorges to leave the country. (18)

The author of the Gaelic American article, the Irish Republican Brotherhood

member Bulmer Hobson, had a chance encounter some years later with Gorges,

who essentially verified the main points in the story. Gorges reportedly added some

further details, stating that the Jewels had once been taken as a joke during a

drinking party by Lord Haddo, and returned the next day. This is said to have

inspired Shackleton and Gorges to repeat the theft, but this time there was to be no

return of the Jewels. According to Hobson, Shackleton disposed of the Jewels in

Amsterdam, stipulating that they were not to be broken up for three years, perhaps

indicating that some sort of ransom back of the stolen goods was intended. (19)

This whole account has the merit of plausibility, even though of course it

comes from a biased source and is uncorroborated in its details. It would not be

unreasonable to suggest that Shackleton’s reference to Haddo in his evidence to the

Viceregal Commission was clearly calculated, a scarcely veiled threat that he was in

a position to reveal embarrassing details about prominent individuals if pressed too

hard by his interrogators. The public exculpation of Shackleton by the Viceregal

Commission is at odds with the exploitation of his association with Vicars in order to

blacken the latter’s name, and points to a remarkable degree of cynicism on the part

of the Government.

It is generally agreed that the doors and safe in Ulster’s Office were left open

deliberately in order to force discovery of the robbery. It is possible that it was Vicars

himself who orchestrated these events when he realised that the Jewels were not

going to be returned, and was thus desperately trying to arrange that someone other

than himself should be on record as discovering the theft, as it happened, the

unfortunate Stivey, who was also to lose his job in the Castle.

Of course it should be noted that Shackleton was not in Ireland in the period

leading up to the theft, and it is suggested that Gorges may have been the one who

actually removed the Jewels, acting on a plan conceived by Shackleton, with both

men sharing in the proceeds of the crime. If this is what happened, it is likely that

Shackleton exploited his intimacy with Vicars to borrow temporarily one of the keys

to the safe, and either the original or a copy may have been used by Gorges to

remove the Jewels. Vicars kept one key on his person and the other concealed in

his house in Clonskeagh, which as already noted he shared with Shackleton. It is

only fair to record that members of the Shackleton family today are not convinced of

Frank’s guilt, pointing to his absence from the country at the time of the theft of the

Jewels and to Chief Inspector Kane’s declaration that no evidence could be found to

show that he was involved. (20) If Shackleton and Gorges were guilty, then they got

clean away with the theft, although both men were later to end up in prison for

unconnected cases involving fraud and manslaughter respectively. Following his

release from prison Shackleton changed his surname to Mellor and died in 1941 in

Chichester, while Gorges appears to have boasted about his role in the Jewels theft

in prison but was not believed, and after his release survived until 1944, when he

lost his life after being struck by a train in London. (21)

Understandably embittered and believing that he had been made a

scapegoat for the theft of the Jewels, Vicars retired to County Kerry, and spent the

remainder of his life in Kilmorna House, which had been made available to him by

his sister, Mrs Edith de Janasz. Vicars married Gertrude Wright in 1917, and on 14

April 1921 he was shot dead by a local IRA unit after it had set fire to Kilmorna. (22)

It is not known whether Vicars was just an incidental victim of the Troubles, or

whether he had actually been providing intelligence on the IRA in an effort to win

back official favour, but it is believed that the killing was a local initiative rather than

an act sanctioned by Republican headquarters. While Shackleton and Gorges were

relatively long-lived, others involved in the Jewels affair came to premature ends:

Pierce Gun Mahony was found shot through the heart in 1914 what appears to have

been a hunting accident, although suspicions of murder were voiced, while Francis

Bennett Goldney died in France in 1918 as a result of a motoring accident. (23)

The full text of Vicars’s last will and testament was not released for public

examination until 1976, as the following rather sensational passage was obviously

considered too incendiary:

I might have had more to dispose of had it not been for the outrageous way in which I was treated by the Irish Government over the loss of the Irish Crown Jewels in 1907, backed up by the late King Edward VII whom I had always loyally and faithfully served, when I was made a scapegoat to save other departments responsible and when they shielded the real culprit and thief Francis R Shackleton (brother of the explorer who didn’t reach the South Pole). My whole life and work was ruined by this cruel misfortune and by the wicked and blackguardly acts of the Irish Government. (24)

It is not usual to employ a will to make such serious accusations effectively from

beyond the grave, and this rather sad and bitter document has certainly helped to fix

the idea of Shackleton’s guilt in the minds of many, without of course providing any

conclusive evidence that he was the culprit.

It should be noted that Francis Bennett Goldney has also come under

suspicion in relation to the Jewels theft, in that after his death in 1918 he was

discovered to have been something of a thieving magpie, and among his

possessions were found ancient charters and documents belonging to the City of

Canterbury, as well as a painting by Romanelli which was the property of the Duke

of Bedford. (25) Goldney’s opportunities and inside knowledge were much less than

Shackleton’s, but we are now aware of his track record, and the theft of the Jewels

occurred just five months after his appointment as Athlone Pursuivant in February

1907. Goldney’s testimony to the Commission is certainly a masterpiece of

deflection and obfuscation, although it is not possible to say whether this proceeded

from elements of his character or a desire to hide something sinister. It must be

pointed out as well that like Shackleton, Goldney was not in Ireland for some months

before the discovery of the loss of the Jewels, but again this does not rule out a

possible organisational involvement in the crime.

Something of Goldney’s style can be seen in an episode when he borrowed

two silver communion cups from Canterbury Cathedral supposedly for exhibition in

America, and on being asked about their return after some months, he claimed

coolly that he been given them to sell, and they are now to be found in the

possession of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. (26) Audrey Bateman,

the principle chronicler of Goldney’s misdeeds, has located Canterbury lore which

shows that there was local suspicion that the mayor had been involved in the theft of

the Irish Crown Jewels. J A Jennings, proprietor of the Kent Herald, recalled that he

had been told by the chauffeur of an American millionaire staying with Goldney in

the Autumn of 1907 that a bigger petrol tank had been fitted to his car before he and

his employer travelled via Dover to Amsterdam, and he was convinced that this

provided the means for the Irish Crown Jewels to be smuggled away. While

Jennings declined to reveal the name of the American, Bateman noted that the

famous and fabulously wealthy art collector John Pierpont Morgan attended Cricket

Week in Canterbury with Goldney in early August 1907. (27) Again it must be

stressed that while there are good grounds for suspicion, there is no conclusive

evidence that Goldney was responsible for stealing the Jewels. Neither should we

hastily convict Morgan, even though there is an indication that he may have been

involved with the export of looted antiquities in the early 1900s, as it has recently

been alleged that he purchased and shipped to New York an Etruscan chariot, which

interestingly is now also in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and whose return to Italy

has been demanded. (28)

The fate of the stolen Crown Jewels remains a subject of speculation and

controversy to the present day. In 1976 an intriguing Irish Government memorandum

dated 1927 was released, indicating that ‘the Castle Jewels are for sale and that

they could be got for £2,000 or £3,000'. (29) Gregory Allen has interpreted these

words to mean that the stolen Jewels were still intact in 1927 and that the thieves or

their agents were effectively endeavouring to ransom them to the Irish Government.

Allen then proceeded to put forward a rather implausible theory that the Jewels may

have been stolen by patriots intent on furthering Arthur Griffith’s plan to secure Irish

independence through the device of a ‘dual monarchy’. (30) Some commentators

have followed Allen in believing that the 1927 memorandum was referring to the

stolen Jewels, (31) but the present writer is not so sure. Might not the reference

have been to the elements of the regalia of the Order of St Patrick not stolen in

1907, the last remnants of which were returned to England as late as the 1940s?

(32) If this interpretation is correct, the belief that the stolen Jewels survived intact

for many years after 1907 appears to be unsupported. As against this, Myles

Dungan has written that a Dublin jeweller, James Weldon, was contacted in 1927 by

Shackleton offering to provide information on the location of the Jewels in return for

money, but this story is based only on Weldon family recollections and is not

documented. (33)

Of course facts or the absence of same should not be allowed to get in the

way of a good yarn, and rumours and legends have abounded over the years, with

claims that the Jewels may still be hidden in Ireland, or somewhere in England, or

alternatively are in the possession of a wealthy collector in America or elsewhere

abroad. The theft of the Irish Crown Jewels has been made the subject of a sexually

graphic novel, which concludes with a mischievous hint that diamonds from the

Jewels may have been incorporated in a magnificent brooch worn by Queen

Elizabeth II. (34) A field in the foothills of the Dublin Mountains was dug up in 1983

by the Gardaí, acting on information received from the granddaughter of an old

republican who had claimed to have been involved in stealing the Jewels, but

nothing was found. On a visit to Listowel some years back the present writer was

shown a clearly forged letter referring cryptically to the Jewels and allegedly written

by Vicars, and an account of strange nocturnal activities among the ruins of

Kilmorna appeared in a newspaper in 1998. (35) The latter shenanigans appear to

have been organised by local jokers for the benefit of two researchers working on

the case, whose account of the Crown Jewels affair has since been published. The

authors claim that the 1907 theft was organised by a Unionist conspiracy in order to

undermine attempts to introduce Home Rule, and that the Jewels were eventually

secretly returned to King Edward. While the authors have uncovered some hitherto

unknown or little used documentation, the present writer does not find the evidence

presented in support of this interpretation of events to be convincing. (36)

Sir Arthur Vicars’s brother, Harry Vicars, featured very little in the story of the

Irish Crown Jewels, and then only in the context of supporting his brother in trying

times. It has recently been suggested to the present writer that Harry Vicars also

should be a suspect in the case, in that there is family lore that he was basically a

crook who cheated his wife Edith Long of her possessions, including having stones

in her jewellery replaced by paste copies. (37) This is interesting information which

deserves further investigation, but again nothing has been proven.

Missing Documents

Reconstructing the story of the Irish Crown Jewels is rendered more difficult

by the fact that a good part of the relevant documentation is wanting or difficult to

access. Thus it is recorded that eight British Home Office files relating to the theft

were officially destroyed, and there is a gap in Ulster’s Office official correspondence

between 1902 and 1908. (38) As noted above, the key report of Chief Inspector

Kane cannot be located. Ulster’s Office actually survived the achievement of Irish

independence in 1922 by some decades, until it was transferred to the College of

Arms in London in 1943 and replaced in the twenty-six counties by the Genealogical

Office/Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland. The surviving records of Ulster’s Office

and the Office of the Chief Herald are combined in a series titled Genealogical

Office Manuscripts in the National Library of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin. (39)

Although permitted to other researchers, access to the unsorted elements of Ulster’s

Office records was refused to the present writer until the intervention of the

Ombudsman resulted in the opening of a proportion only of the material in 2006.

Bamford and Bankes wrote in 1965 of the ‘cloak of secrecy and evasion’ then still

surrounding the Irish Crown Jewels case, (40) and while most officials approached

were glad to assist the present writer’s research, it seems that old attitudes have not

entirely died out in certain quarters. (41)

From my necessarily constrained research in Ulster’s Office records, I can

confirm that there may well have been contemporary official weeding of material

relating to the theft of the Jewels, which tends to support the view that this was no

ordinary crime, but a wider scandal drawing in members of the establishment and

their connections. One is also struck by the disorder in which the surviving Ulster’s

Office correspondence of the period remains, which problem is complicated by the

chaos into which some of the records of the Office of the Chief Herald collapsed in

the course of the Mac Carthy Mór scandal, a more recent event which bears not a

few passing similarities to the Irish Crown Jewels affair. (42) Thus the volumes of

copies of Ulster’s outward correspondence are not all clearly dated and numbered,

while files of inward correspondence are very disordered (the writer was intrigued to

find inserted among correspondence of the early 1900s a 1983 letter to Chief Herald

Donal Begley from the bogus Irish chief Terence MacCarthy!). (43) All of this puts

National Library staff to considerable trouble to produce specific material, as well as

multiplying the number of visits which a researcher must make. The writer has

recommended to the Library Board that it should remedy without further delay the

long-standing problem of the inadequately catalogued and sometimes disordered

state of Genealogical Office manuscripts. These are important records historically as

well as in relation to heraldry and genealogy, and until they are properly arranged

and catalogued one cannot be certain that they do not contain any additional

information relating to the theft of the Irish Crown Jewels in particular.

It is a commonplace observation that the relentless development of Dublin in

recent decades, and particularly during the Celtic Tiger boom, has seen the

destruction of much of the old fabric of the city. Yet remnants and relics of the past

sometimes surprisingly survive, and this is certainly true in the case of the Irish

Crown Jewels. For a start, despite the internal reconstruction of the Bedford Tower

in Dublin Castle as a conference centre, still effectively intact is the old Ulster’s

Office Library in which stood the safe from which the Jewels were stolen in 1907.

The Ratner safe itself was transferred to Kevin Street police station in 1908,

remaining there until returned in December 2007 to Dublin Castle, where it may be

viewed in the Garda Museum now occupying the Bermingham Tower (ironically this

was where the safe was first located before Ulster’s Office moved to the Bedford

Tower in 1903). The house shared by Vicars and Shackleton still stands in St

James’s Terrace, Clonskeagh. There was formerly a display case containing a

police reward poster and other items relating to the Irish Crown Jewels in the State

Heraldic Museum in the National Library in Kildare Street, but the Museum was

removed during the very centenary of the theft in 2007 to make way for a new

National Library exhibition on the Irish in Europe, and it has not been possible to

clarify the fate of the display case. Of the Irish Crown Jewels themselves no trace of

course can be found, and the writer inclines to the view that whoever stole them,

they would have been broken up and sold on at some point subsequent to the theft.

Conclusions

In the light of the foregoing analysis of documentary evidence relating to the

theft of the Irish Crown Jewels in 1907 and study of various accounts of the crime,

the conclusions of this report are as follows:

(1) While considerable documentation relating to the loss of the Irish Crown Jewels survives, certain key official records appear to have been deliberately destroyed, making it difficult if not impossible to establish exactly what happened.

(2) The Viceregal Commission of investigation into the loss of the Irish Crown Jewels was more concerned with scapegoating Sir Arthur Vicars than uncovering the full facts relating to the affair, and was in essence a whitewash.

(3) Those accounts of the theft of the Irish Crown Jewels which postulate that it was probably an inside job are most likely correct, and while the identity of the mastermind behind the crime has not and may never be proven conclusively, the prime suspect remains Francis Shackleton, with Francis Bennett Goldney a strong suspect number two.

Sean J Murphy

25 January 2008, last updated 29 April

References

(1) The present report is a development of the author’s Irish Historical Mysteries series article, ‘The

Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels’, which it now replaces. Thanks are due to the staffs of the National

Library of Ireland, the National Archives of Ireland, Dublin Castle, the Garda Museum, the National

Archives (Kew) and other individuals mentioned in the notes below. The best general chronicle of the

affair remains Francis Bamford and Viola Bankes, Vicious Circle: The Case of the Missing Irish Crown

Jewels, London 1965, and the author has also made use of other accounts as cited below.

(2) Report of the Viceregal Commission Appointed to Investigate the Circumstances of the Loss of the

Regalia of the Order of St Patrick, London 1908, hereafter cited as Crown Jewels Commission

(Ireland). The National Archives of Ireland has placed online copies of the Commission’s report

(excluding the appendices) and a range of official records relating to the Irish Crown Jewels affair at

http://www.nationalarchives.ie/topics/crown_jewels/gallery.html. The most important National Archives

file is CSORP/1913/18119, portions of which are included in the online reproductions.

(3) Peter Galloway, The Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick 1783-1983, Chichester, Sussex, 1983,

page 96.

(4) Crown Jewels Commission (Ireland), Report, page iv.

(5) Same, pages vi-viii.

(6) Séamus Shortall and Maria Spassova, Pierce O’Mahony: An Irishman in Bulgaria, [2002].

(7) Crown Jewels Commission (Ireland), Report, page ii.

(8) Same, page iii.

(9) Same, Appendix, Minutes of Evidence.

(10) Same, page 79.

(11) Same, page 70.

(12) Same, page 76.

(13) Same, page 77.

(14) Same, Report, page xi.

(15) Same.

(16) Roland Huntford, Shackleton, London 1996 edition, page 184.

(17) Irish Times, 1 and 3 February 1908, retrieved from http://www.ireland.com/search, 17 January

2008.

(18) ‘Abominations of Dublin Castle Exposed’, Gaelic American, 4 July 1908.

(19) Bulmer Hobson, Ireland Yesterday and Tomorrow, Tralee 1968, pages 85-88.

(20) Communications from two members of the Shackleton family, January 2008. It was not long

before the reputations of Shackleton and Gorges came to the attention of the authorities, for example,

the Earl of Kilmorey sent Lord Aberdeen a letter (undated, pre-December 1907?) in which he

described the two as ‘unspeakable scoundrels’ of ‘filthy character’, accusing them of responsibility for

the theft (Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, D2638/D/46/4, copy courtesy of Kevin Hannafin).

(21) David Murphy, Letter to History Ireland, 10, Number 1, 2002, page 11; death certificate of Richard

Gorges 1944 (copy courtesy of Kevin Hannafin).

(22) Bamford and Bankes, Vicious Circle, pages 189, 197-201.

(23) Audrey Bateman, The Magpie Tendency, Whitstable, Kent, 1999, page 80.

(24) Will and Probate of Sir Arthur Vicars, 1922, National Archives of Ireland.

(25) Bateman, Magpie Tendency, pages 82-83, 85 and generally.

(26) Same, page 85.

(27) Bateman, An account by J A Jennings, proprietor of the Kent Herald at the time the Irish Crown

Jewels were stolen, unpublished, 2004 (copy courtesy of Arthur Evans).

(28) ‘Umbrian Umbrage: Send Back That Etruscan Chariot’, New York Times, 5 April 2007,

http://www.nytimes.com, visited 24 January 2008; it has since been claimed that the chariot is in fact a

fake.

(29) Portion of Memorandum 1 June 1927, National Archives of Ireland, S 3926 A.

(30) Gregory Allen, ‘The Great Jewel Mystery’, Garda Review, August 1876, pages 16-22.

(31) Tomás O’Riordan, ‘The Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels, 1907', History Ireland, 9, Number 4,

2001, page 27.

(32) Galloway, Illustrious Order of St Patrick, page 72.

(33) Myles Dungan, The Stealing of the Irish Crown Jewels: An Unsolved Crime, Dublin 2003, pages

250-51.

(34) Robert Perrin, Jewels, London and Henley 1977, page 269.

(35) The Kerryman, 21 August 1998.

(36) John Cafferky and Kevin Hannafin, Scandal and Betrayal: Shackleton and the Irish Crown Jewels,

Cork 2002, pages 216-234 and passim.

(37) Information of Ian Macalpine-Leny, November 2007.

(38) Susan Hood, Royal Roots, Republican Inheritance: The Survival of the Office of Arms, Dublin

2002, pages 62-63. The surviving documentation on the Irish Crown Jewels in the English National

Archives is substantial but clearly weeded , for example, HO 144/1648/156610, marked ‘Closed until

2022', yet inspection now permitted (copy of file ordered online at http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk).

(39) Of particular interest is Ulster’s Office Correspondence, bound volumes (outward) and files

(inward), Genealogical Office Manuscripts, National Library of Ireland, not fully sorted or referenced.

GO MS 507, a useful scrapbook of newspaper cuttings and correspondence relating to the loss of the

Irish Crown Jewels, compiled by J C Hodgson and presented to Ulster’s Office in 1942, compensates

in some measure for removed or misplaced official documentation. See also Fuller Papers 1904-15,

NLI microfilm POS 4944, which contains correspondence of Vicars, some of it relating to the Irish

Crown Jewels.

(40) Bamford and Bankes, Vicious Circle, page 202.

(41) While National Library desk staff have been consistently helpful in relation to the writer’s Irish

Crown Jewels research, e-mail queries sent on 17 December 2007 to the Office of the Chief Herald

and on 14 January 2008 to the Director of the National Library and the Chairman of the Library Board,

have not been dealt with (as of April 2008).

(42) Sean J Murphy, Twilight of the Chiefs: The Mac Carthy Mór Hoax, Bethesda, Maryland, 2004;

see also ‘The Mac Carthy Mór Hoax’,

http://homepage.eircom.net/%7Eseanjmurphy/irhismys/maccarthy.htm.

(43) The writer’s initial examination of the newly released Ulster’s Office material among the

Genealogical Office manuscripts has uncovered evidence that the removal of records may have been

unauthorised as well as official, in that one volume of correspondence dated 1901-02 has a note

attached to the flyleaf which reads, ‘Bought from Townley Searle, 30 Gerrard Street W I for 10s,

10.10.1941'. Searle appears to have been a London author and bookseller, and his possession of this

volume and perhaps other records simply adds another layer of mystery (one might point to the

coincidence that 1941 was also the year of Frank Shackleton’s death).