Irish Historical Mysteries: The Trade in Joyce Manuscripts

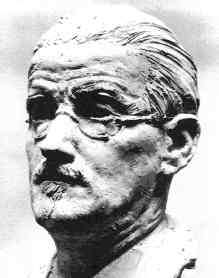

James

Joyce (1882-1941)

(Sculpture

by Jo Davidson, photograph by François

Kollar, © Mission de Patrimoine Photographique)

Part 1: The Léon Cache

Why

did he desist from

speculation?

Because it was a task for a superior intelligence to substitute other

more acceptable

phenomena in place of the less acceptable phenomena to

be removed.

James Joyce, Ulysses,

1922 Text, page 650.

James Joyce's Ulysses,

modelled on Homer's Odyssey

and describing the wanderings and encounters of Leopold Bloom and

assorted characters in Dublin on 16 June 1904, is perhaps the

most acclaimed, but not necessarily actually read, novel of our

time. While Joyce has a number of informed devotees among the

general reading public, there is a perception that his works have

in general been captured by an enclosed, academic elite or church

which spends its time jargonising and theologising over the

deeper significance of the author's every word. Consider for

example the following: 'In effect, Joyce's writing exacerbates

the question of materiality by reaching constantly beyond the

assumes limits of signifying probability, and by situating the

"nexus" of semio-linguistic structure in its

materiality and not in some form of anima or agency

"deposited in it"-as Frederic Jameson, among others,

suggests when he states that the "pure temporal movement of

signification itself, as it deposits itself in object or letter,

is retained, without any ultimate sense of the direction or

meaning of that movement."' (1) Come again?

Notwithstanding the excesses of

his

exegetists, the stock of James Joyce has never been higher, as

demonstrated by the huge sums fetched by manuscripts and first

editions of his works in recent years. Thus in December 2000 the

National Library of Ireland purchased from Christie's in New York

a 27-page draft of the Circe episode in Ulysses,

at a

cost of US$1.4 million. (2) The name of the vendor was not

released, but it was stated to be a relative of John Quinn, a

wealthy New York lawyer who had acquired material from Joyce.

There was a general welcome for the purchase of the Circe

manuscript, and it was clear that thanks to the 'Celtic Tiger'

economy, the National Library was no longer starved of the funds

necessary for such major purchases. Yet there was also some

surprise expressed that the Circe manuscript had surfaced, as it

had been considered that there was no longer any such material

remaining to be discovered.

Flushed with this success, the

National

Library took the opportunity in July 2001 to purchase from

Sotheby's of London for £55,000 what it thought was an

original

death mask of Joyce. Unfortunately, it was brought to the

attention of the National Library and its Director, Brendan O

Donoghue, that all surviving original Joyce death masks were

accounted for, and that the mask on offer was in fact a copy. The

Library immediately cancelled the sale, but the affair was a

considerable embarrassment and revealed a worrying deficiency of

expertise. (3) Another unexpected Joycean find, a notebook

relating to the Eumaeus episode in Ulysses,

was also

sold by Sotheby's at the same auction session for US$1.5 million,

but the National Library decided not to join the bidding for this

item.

It would later emerge that the

Library

was

in any case at this time engaged in top secret negotiations for

the purchase of a collection of Joyce manuscripts much larger

than any of those which had hitherto come to light. A

considerable international sensation was created when on 29 May

2002 the then Minister for Arts and Heritage, Síle de

Valera,

stepped from the Government jet at Dublin Airport carrying a

suitcase containing Joyce papers which had been acquired for

€12.6 million. The immediate charge to the public purse was

leavened by the fact that half the cost was to be paid by Allied

Irish Banks, taking advantage of the so-called Section 1003 tax relief

procedure. At a

press conference in the National Library on the day following, 30

May, the full extent of the acquisition was revealed: notebooks

from the author's early period, preparatory notebooks for and

drafts of episodes of Ulysses,

and proofs of Finnegans

Wake. (4)

The vendors of the material were

a Mr

and

Mrs Alexis Léon of Paris, with Sotheby's acting as their

agents.

Alexis Léon is the son of Paul Léon, a close

friend of

Joyce

who donated his own personal correspondence and papers to the

National Library as a free gift before his death at the hands of

the Nazis in 1942. (5) Joyce had left Paris with his family in

1939 and then moved to Switzerland, dying of a perforated ulcer

in Zurich on 13 January 1941. Despite the danger that Paul

Léon

faced from the Germans on account of his Jewish faith, he bravely

made several trips to Joyce's Paris flat to remove material for

safe keeping on the family's behalf. Characteristically, Joyce

had departed his flat hurriedly leaving rent arrears, so that the

landlord was planning to auction off his effects, and there was

also a danger that possessions would be looted by rapacious

Nazis.

The present writer was concerned

about

certain aspects of the May 2002 purchase, particularly how the

manuscripts sold by the Léons could be differentiated from

material Joyce had left behind in his flat. For example, a series

of Joyce's notebooks for Ulysses,

numbered 1, 2, 4, 6, 7

and 8 are in Buffalo University and can be acccounted for in that (as

the writer has been informed) 1, 2, 4 and 7 were sold on by Sylvia

Beach, while 6 and 8 were among material sold by Joyce's family to the

university after the war, which material had earlier been duly returned

to

its possession in accordance with Paul Léon's instructions. The missing

notebooks numbered 3, 5 and 9 are among the manuscripts acquired from

the Léons by

the

National Library, and the question arises as to whether these might

have somehow become detached from the material Paul Léon had rescued on

Joyce's behalf, or whether they could have been an earlier gift to him

from Joyce. (6) Alexis Léon was quoted at the time of

the

2002 sale as insisting that the manuscripts had nothing to do with

the documents which his father had rescued from Joyce's flat. Yet one

Internet commentator observed, 'The way this is

phrased suggests to me that Alexis Léon knows he's on shaky

ground in claiming ownership'. (7)

As a long-time user of the

institution,

the

present writer felt entitled to make a Freedom of Information Act

application to the National Library, and documents released in

October 2002 showed that the sale of the manuscripts had not in

fact gone entirely smoothly. It emerged that the Joyce Estate,

headed by Joyce's grandson Stephen James Joyce, had heard of the

planned sale on the grapevine. The Estate's solicitors, McCann

FitzGerald, made its own FOI application on 18 April 2002 to

Minister de Valera, in an effort to find out what was happening.

On 29 April National Library Director O Donoghue advised that the

solicitors' FOI application should be refused on the grounds that

it might compromise ongoing negotiations, and furthermore that

such refusal should be couched 'in terms which do not even

acknowledge that such a purchase is being contemplated'. The

Library's FOI release to the present writer was minus a

substantial proportion of documents relating to the sale,

including the sale contract. These documents were withheld on the

rather startling grounds that they could be used in a legal

challenge which could 'call into question the whole transaction

with possible significant exposure to the State and the National

Library'. (8

The first public airing of the

controversy

over the Joyce manuscripts was in the edition of Phoenix

magazine dated 17 January 2003. Stephen James Joyce went on the record

with his concerns in the Irish edition of the Sunday

Times

on 16 February 2003, challenging Alexis Léon to produce

proof

that the manuscripts were in fact his mother's property. Joyce

stated that the Estate did not have 'any strong wish to get

involved in litigation', but added ominously, 'If we feel we have

to take action, we will'. Also subject to criticism were the

National Library and the Government, on account of the secrecy

surrounding the purchase, and the failure to keep the Estate

informed, 'as it was in the past under similar circumstances'.

The writer understands that prior to the sales of the 'Circe' and

'Eumaeus' materials, the Joyce Estate was fully briefed, and it

is hard to understand why this courtesy was not observed in the

case of the Léon cache sale.

While Alexis Léon

resolutely

refuses to

comment further, National Library Director Brendan O Donoghue

merely repeated that 'the vendors asserted that they were the

legal and beneficial owners of the materials and were entitled to

sell them'. Alas, that does not constitute proof of ownership or

evidence of due diligence in establishing the provenance of the

disputed materials. Indeed courts internationally have been

taking a more critical view of secrecy and failure to inquire

before purchase in the case of assets whose ownership is in

dispute as a result of the dislocation of war. Appeals to the

Statute of Limitations and attempts to transfer the burden of

documentary proof to the plaintiffs are not being regarded in a

legally favourable light. Those who consider

that passage of time renders

restitution a moralistic irrelevance might ponder the case of a

collection of paintings by Gustav Klimt,

stolen by Nazis in 1938 and now valued at £170 million, which

by

court

order were restored by a Viennese gallery in March 2006 to an heiress

resident in California (Guardian, 21 March 2006).

The publicity concerning the

Joyce

manuscripts also led to the matter being the subject of

parliamentary questions in the Dáil. Fine Gael spokesman

Jimmy

Deenihan asked the present Arts, Sport and Tourism Minister John

O'Donoghue to state if the sellers Mr and Mrs Alexis Léon

had

'proper legal title' to the manuscripts. Minister O'Donoghue

replied on 13 February 2003, repeating the by now familiar line

that the vendors 'asserted that they were the legal and

beneficial owners of the materials', and that the 'contract for

sale entered into with the vendors reflects this position'. Emmet

Stagg for Labour followed up with a question about the 'potential

legal case' which may be taken against the State in connection

with the manuscripts purchase. In his reply on 26 February

Minister O'Donoghue merely referred back to his earlier answer.

(9)

Full colour digital images of the

Joyce

manuscripts in question have now been made available to scholars

on a high resolution computer screen in the National Library

Manuscripts Reading Room in Kildare Street, Dublin. (10)

Reflecting the fact that while ownership of the manuscripts may

lie with the Library, the copyright remains with the Joyce

Estate, it is necessary to sign a declaration agreeing to abide

by legal conditions of use. The speed with which copies of the

Joyce manuscripts have been made accessible is to be commended,

but there should be no question of access to the originals being

decided on the basis of grace and favour, as alas is the case

with certain uncatalogued Library manuscripts. (11) The writer

also cannot help drawing a contrast between these colour digital

facsimiles and the semi-legible half-century old microfilm and

scratched and indistinct microfiche via which some other records,

particularly of a genealogical nature, must still be viewed in

the Library.

In the Irish

Times of 30 April

2003 journalist and Joycean expert Terence Killeen wrote a fairly

lengthy and impassioned piece decrying attempts to unravel the

mystery of the provenance of the Joyce manuscripts. Accepting

that 'some of the manuscripts have clearly been separated from

others of which they once formed part', Killeen hypothesised

lyrically to the effect that 'Joyce's life was an odyssey without

an Ithaca', and that 'in the course of his many wanderings, items

might well have become separated from each other'. Killeen also

effectively justified the National Library's 'reticence' about

dispelling the cloak of secrecy enveloping the transaction, on

the grounds of threatened legal action.

Killeen's piece was overtaken by

events,

in

that in contrast to the National Library's refusal, the

Department of Arts, Sport and Tourism had decided on 29 April

2003 following a Freedom of Information appeal to release the

Joyce manuscripts sale contract, albeit with significant

deletions. The contract is dated 22 May 2002 and is between the

vendors Mr and Mrs Alexis Léon, their agents Sotheby's, and

the

purchaser, Minister de Valera, with the latter authorising

Library Director O Donoghue to sign on her behalf. Payment for

the manuscripts was scheduled in three instalments, due on 30 May

2002, 28 February 2003 and 28 February 2004, at which latter date

all the goods became the property of the purchaser. The contract

includes a clause allowing for the sale to be rescinded in the

event that evidence raising doubts as to the authenticity or

attribution of the items is presented, a sensible precaution in

the light of the earlier unfortunate Joyce death mask transaction

between the Library and Sotheby's. While the manuscripts were

closely scrutinised by Joycean literary experts, it does not appear that they were examined by a

qualified forensic documents expert with regard to handwriting, ink

and paper.

The contract states that the

vendors are

'the full legal and beneficial owners of the property', but

section 6, 'Warranties by the Vendors', has been subjected to

severe pruning. This is unfortunate, as this is the very portion

of the contract which might have been expected to allay doubts

about the vendors' title to the manuscripts. The Arts Department

justifies the deletions on the grounds that 'premature disclosure

of the contents of these clauses could reasonably be expected to

result in undue disturbance of the ordinary course of business,

and in this context could result in an unwarranted financial cost

to a person or persons and/or to a public body'. The withholding

of the vendors' warranties was again appealed to the Information

Commissioner, who ruled in favour of the Department in December

2003 on the somewhat enigmatic grounds that 'the disclosure of

the information would, of itself, be an unauthorised use of that

information to the detriment of the party communicating it'.

While a statement by Alexis

Léon dated 24

April 2001 had thus been withheld, certain documents appended to

it were released. Because Alexis Léon has consistently

refused

to make further comment, these documents provide the only

available clues as to the possible nature of his case for

ownership. The documents include firstly extracts from the

published memoir of Alexis's mother Lucie Léon (aka Noel),

in

which she describes how her husband Paul had rescued materials

from Joyce's Paris flat during World War II and arranged for them

to be held safely for the benefit of Joyce's family. Lucie

Léon's account also mentions 'a suitcase with important

Joyce

papers in our apartment', and there is an inference that this is the

collection now sold to the National Library. Yet

the context clearly raises questions concerning such a

connection, as Lucie also recorded that she had attempted to

deposit the suitcase with the Swiss Legation, on the grounds that

'Mr Joyce carried a British passport' and the Swiss were

protecting British interests, implying that the material was

being held in trust for the Joyce family and was not in fact her

property. (12)

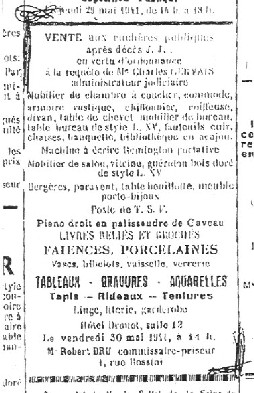

Notice in Gazette Hôtel Drouot, 24 May 1941

Secondly,

the appended documents include

a

published notice in French concerning a sale on 30 May 1941 at

the Hôtel Drouot in Paris of goods of the deceased 'J. J.',

presumably James Joyce (see copy above). The sale is stated to be

at the request of the 'administrateur judiciaire', which would

indicate that it was legally authorised, although in the

confusion of war all the niceties may not have been observed.

Lucie Léon referred to an apparently earlier sale arranged

by

Joyce's landlord and held in the Hôtel Drouot on 7 March, but

the writer is informed that this is a misstatement as there was

only one sale. The goods on offer at the May sale included

furniture, miscellaneous items and books, with no apparent

mention of any manuscripts as such. Yet the inclusion of the sale

notice as an appendix to the 2002 contract might tend to suggest

that the Léons' title to at least some of the disputed

manuscripts may be based on a claim of specific purchase.

If this is the case, why continue

to

withhold the vendors' warranties, and why not produce more firm

evidence such as a bill of sale? Why the continuing secrecy, and

the frankly provocative decision to refuse the Joyce Estate

information which might allay its concerns? In short, why prolong

a controversy unnecessarily by refusing to be more transparent in

relation to the expenditure of a sum of public money as large as

€12.6 million? At a time when fiscal rectitude has resulted

in cuts in health and education, and inevitably also restrictions

in cultural spending, these questions take on an even greater

urgency.

The plot thickened further with

the

revelation that James Joyce's will was probated

belatedly in Ireland in September 2003. The

probate was taken out on behalf of the Joyce Estate, an action

obviously designed to protect its legal interests. (13) Meanwhile, the trade

in Joyceana continued, and Sotheby's concluded another spectacular sale

in July

2004, which included an explicit three-page letter sent by the

author to his wife Nora in 1909. This letter had supposedly lain

for the best part of a century 'hidden in the pages of an old

book' complete with its stamped envelope, and was purchased by an

anonymous bidder for the staggering sum of £240,800. A play had actually been written in 2001, entitled Her Song be Sung,

and performed in Dublin in 2004 before the sale, which imagined just

such a discovery of an erotic Joyce letter in an old book

(http://www.abc.net.au/rn/arts/bwriting/stories/s1196227.htm). It is

true that fact can be stranger than fiction, but sometimes fiction

masquerades as fact . . .

The National Library and the

Irish State staked a lot on the 2002 purchase of Joyce manuscripts,

these forming the centrepiece of a Bloomsday Centenary

Exhibition which opened in the Library in June 2004. In order to

circumvent feared objections from the Joyce Estate to this

exhibition, the Government put through a special amendment to the

Copyright Act 2000 which allows for public display of artistic or

literary works without reference to the creators or rights

owners. (14) It would have been preferable if the Joyce Estate

and the Irish Government had arrived at a mutually acceptable

resolution of their differences before the Centenary of

Bloomsday, but the National Library and the Department of Arts

decided on a hardball approach which exacerbated rather than

eased tensions. The controversy over the Léon cache of Joyce

manuscripts has been in some respects akin to a game of high-stakes

poker, with the winning hand not fully shown. The Joycean community in

general appears not much

troubled by the doubts surrounding the origin of the manuscripts,

perhaps because it is considered that the successful capture of

such an important element of Joycean heritage for Ireland renders

ethical objections petty or irrelevant. The current position is

that some years after the purchase of the Léon cache of

Joyce

manuscripts, we are still pretty much stranded in the dark of

Nighttown, with outstanding questions concerning the collection's

provenance and ownership unanswered and likely to remain so

indefinitely.

Part 2: The Barnes Cache

Who can

say how many pseudostylic shamiana, how few or how many of the most

venerated

public impostures, how very many piously forged palimpsests slipped in

the first place by

this morbid process from his pelagiarist pen?

James Joyce, Finnegans Wake,

1939, Penguin Edition 1992, pages 181-82.

In the light of the various finds of

Joyce manuscripts

outlined above, it seemed to the present writer that it was a question

not of if but when the existence of a new cache would be revealed

to the world. I wondered to myself whether controversy

would again follow the announcement of a new find, and if this

time the materials might relate not to Ulysses,

but to Joyce's last and

most difficult work, Finnegans Wake.

So exactly it came to pass when in March 2006 the

National Library announced that

it had paid €1.17 million for more Joyce manuscripts,

consisting of six large sheets containing 1923

drafts of portions of the work which would become Finnegans Wake. (15)

The Library did not immediately release

the name of the individual

from whom it had purchased the Finnegans

Wake manuscripts, but

there were indications that he or she was based in France. However, in

response to questions, the Library eventually revealed that the vendor

was a certain

Laura Barnes. Following further enquiries, the Library confirmed that

this individual was also known as Laura Rosenfeld and Laura Weldon.

Under the latter name, she had been co-ordinator of the above mentioned

Bloomsday

centenary celebrations, ReJoyce 2004, and was very well known to the

Library. (16) A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Rosenfeld is her birth

name, but

in her professional work as a rare book dealer and proprietor of Araby

Books she generally uses the name Laura Barnes. In 2006 Ms Barnes was

appointed acting director of

the government-funded James Joyce Centre in North Great

George’s Street in Dublin.

Laura Barnes

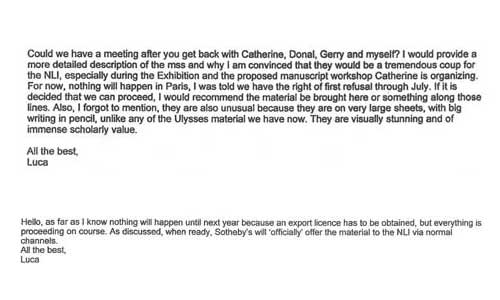

Freedom of Information applications uncovered more detailed information concerning the background to the Finnegans Wake manuscripts deal. In particular, it appeared that in mid-2004 the National Library had an opportunity to acquire the manuscripts from a rare book dealer in Paris, Jean-Claude Vrain. The Library’s Joyce Research Fellow, Dr Luca Crispi, stated on 29 June 2004 that the Library would have ‘right of first refusal through July’. However, in a sequence of events which still remains obscure, Ms Barnes/Rosenfeld/Weldon managed to acquire the manuscripts from Vrain, and then moved to negotiate their resale to the Library via Sotheby’s of London. (17) The FOI releases contain no documentation whatsoever concerning the manuscripts between 29 June and 5 October 2004, in itself a remarkable hiatus, and making it difficult to explain how the opportunity to acquire the manuscripts from Vrain was lost. On 12 October 2004 Dr Crispi stated that nothing would happen until 'next year', but that everything was 'proceeding on course' and that Sotheby's would 'officially' offer the manuscripts to the Library 'via normal channels'. It is reasonable to ask whether Sotheby's was acting for Vrain or for Barnes at this point? Library Director Ó hAonghusa has been quoted as stating that Sotheby's could provide reliable warranties as to provenance and ownership which a small Parisian book-dealer could not. This overlooks two facts, firstly, that Sotheby's was mentioned as a potential agent as early as June 2004, and secondly that the fallibility of this firm's judgement was demonstrated during the affair of the Joyce death mask recounted above.

Extracts

from e-mails

from Dr Luca Crispi, 29 June and 12 October 2004

(National Library of Ireland FOI

releases)

How the Finnegans

Wake manuscripts slipped from the National Library's grasp in

2004 and into the hands of Laura Barnes remains therefore something of

an unresolved

mystery. While serious negotiations to purchase the manuscripts got

under way with Ms Barnes's agent Sotheby’s

in

December 2004, it was not until June 2005 that the Library was in a

position to sign a contract of sale, having secured funding support

from Allied Irish Banks via the Section 1003 tax relief provision. The

identity of the vendor Ms Barnes was stated not to have been revealed

to the Library until as late as May 2005, and in February 2006

Sotheby’s informed National Library Director Aongus

Ó hAonghusa that

‘she would obviously prefer it if her name did not come out

at all’.

The contract described the vendor of the manuscripts as

‘Laura

Rosenfeld (also known as Laura Barnes)’, but contained a

confidentiality clause stating that the details of the contract should

not be released, save as might be required legally or in response to an

FOI application. (18)

There was a further remarkable

revelation in May 2006, when

it was

reported that Ms Barnes had purchased the manuscripts

for €400,000, meaning that the Library may have paid in the

region of €700,000 more than it needed to, had it acted to

acquire the

material from its Paris owner. It was also claimed that a Finnegans

Wake notebook had been on

offer with the manuscripts, but that this

had been sold to a buyer whose identity remains unknown and therefore was lost to the Library.

(19)

The provenance of the Finnegans

Wake manuscripts is

problematic as well, arising from mystery over the fate of possessions

left in Joyce’s Paris flat when he departed it in 1939. As

outlined in the first section of the present article, it is

known

that some

assorted goods of Joyce were seized by his landlord in lieu of

outstanding rent and auctioned in the Hotel Drouot in 1941. No evidence

has been produced to confirm that any substantial manuscripts were

involved in this

auction, and indeed, as noted above, it is recorded that

Joyce’s friend, Paul

Léon, had

removed manuscripts from the flat for safe keeping and eventual return

to Joyce’s heirs. It is claimed that the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts

were purchased in 1945 or 1946 at an auction in the Hotel Drouot by a

book dealer, Maurice Bazy, from whose estate they were acquired by

Jean-Claude Vrain some years ago. However, Joyce Fellow Dr Crispi, one

of the world’s leading authorities on Joyce’s

manuscripts, advised

Director Ó hAonghusa in May 2005 that ‘there is no

way of knowing

precisely when these materials were bought’, adding nevertheless,

'I think we are on safe ground here'. (20) What is to be said therefore

about the provenance details supplied by Sotheby's?

The Finnegans Wake manuscripts acquired

by the National Library consist of 6 large large sheets containing 11

pages of text, written between April and August 1923, comprising drafts

of the sketches called 'Tristan and Isolde', 'Mamalujo' and 'St Kevin'.

These manuscripts appear to be the earliest surviving drafts of the

work which would be published sixteen years later as Finnegans Wake,

and are alleged to

have survived unnoticed for half a century, 'interleaved' in a book,

recalling the above mentioned mode in which Joyce's erotic letter of

1909 was discovered.

Two further remarkable features of the manuscripts are the fact that a

significant portion of the text was never published by Joyce and is therefore

unknown, and that 6 of the pages are in the handwriting

of Nora Barnacle at the author's dictation, demonstrating a

hitherto undocumented degree of collaboration between husband and wife.

The Joycean scholar Danis Rose

has claimed controversially that Joyce first

conceived Finnegans Wake as a

distinct work to be called Finn's

Hotel, which he did not complete, and at first sight this

new

manuscripts find seems to fall in with his theory.

As in the case of

the Léon cache of manuscripts, it does not appear that the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts were

double checked by a forensic documents examiner in addition to

examination by Joycean experts, and in view

particularly of the problematic provenance and quantity of hitherto

unknown

text, this would be a prudent precaution (which the present writer has

in fact recommended to the Director and Board of the National Library,

without receiving any response on the issue). Having several times

examined digital copies of the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts in the National Library the present writer retains a

distinct sense of unease concerning their authenticity, while

acknowledging that he is neither a Joycean specialist nor an expert in

forensic document examination (although his work in discovering

falsified documentation in the cases of the spurious chiefs Mac Carthy

Mór and Akins of That Ilk entitles him to claim some measure of skill in

regard to the latter). A running joke in Finnegans Wake

is the use of '1132' as an absurd catch-all date, for example, 'the

official landing of Lady Jales Casemate, in the year of the flood

1132', and an appearance 'round about the freebutter year of Notre Dame

1132' by 'Motham General Bonaboche' (Penguin Edition 1992, pages

387, 388). The Finnegans Wake drafts

feature recognisable versions of both these sequences, firstly,

'the capture of Sir Arthur Casement in the year 1132', and secondly,

'the dispersal of the French fleet under General Boche in the year

2002' (Joyce 2006 Papers, National Library of Ireland Manuscripts

Reading Room, on computer). I was admittedly pulled up short by the

sudden appearance of '2002' where '1132' might have been expected, and

wondered what Joyce (if it was he) was about in suddenly pointing to

the future rather than the past, and why '2002' does not feature in the

final edition of the Wake. Noted also was the fact that the computer on which I was viewing the Wake

manuscript also contained images of the Léon cache, titled 'Joyce

Papers 2002'. Perhaps, you may say, Joyce was clairvoyant as well as

mischievous, or possibly this is a matter of absolutely no import, or

perhaps again there is a more peculiar game in play . . . (The Joycean Sam Slote has now endeavoured to explain the dating differences between the draft and final versions of Finnegans Wake,

noting that 'additional dates were eliminated and 1132 became general

over Ireland, thereby imposing another lattice of intercorrespondence

and inter-connection between elements on the list', going on to suggest

a 'fungibility of historical events', asking 'what is the mish and what

the mash?' and identifying a 'realm where the onerous category of error

could well be erroneous'. Quite.)

The covert aspects of the Finnegans

Wake manuscripts deal and the slow release of information

resulted in the story remaining in the news in the months following the

National Library's announcement in March 2006. By early June 2006 it

had

emerged that close connections

existed

between Laura Barnes, Dr Crispi and his wife, Dr Stacey Herbert. (21) Barnes

has worked with Crispi and Herbert on Joycean projects in the United States.

Barnes and Herbert acted as curators

of a Beckett exhibition in the National

Library

in 2006, and

Herbert has also been associated with Barnes’s Araby

Books. Interestingly, the signatures of both Laura Rosenfeld and Luca

Crispi appear on the June 2005 contract of sale of the Finnegans Wake manuscripts.

Credits for Joyce Exhibition at Buffalo University 2000

In the light of all these circumstances, it seemed

reasonable

to

pose certain questions. Was Jean-Claude Vrain able to provide

documentary

evidence that the Finnegans Wake manuscripts were

purchased at

auction in Paris in the 1940s? Were the manuscripts subjected at any

stage to the

analysis of what they term in the USA a ‘questioned

documents’ expert?

On what date did Laura Barnes agree the purchase of the manuscripts

from Jean-Claude Vrain, and what became of the National

Library’s right

of first refusal? Is it true that the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts were resold to the National Library for a profit of about

€700,000? Were there formal or informal discussions

concerning the Finnegans

Wake manuscripts between

Laura Barnes, Dr Luca Crispi, Dr Stacey

Herbert and National Library Director Aongus Ó hAonghusa in

the period

January-December 2004? Unfortunately, no answers to these questions have been

forthcoming to date. (22)

While Laura Barnes has declined

to reply to any of the present writer's correspondence, she was the

subject of a pre-Bloomsday 2006 Irish

Times interview which touched on the Finnegans Wake manuscripts

controversy. (23) Ms Barnes declared that 'if you connect the dots in

an inappropriate way, you come out with an inappropriate picture'.

Unfortunately, far from answering questions already posed, this

interview raises further questions concerning the Finnegans

Wake material. For example, Ms

Barnes was quoted as follows in the Irish

Times of 15 June 2006: '. . . the

decision I made was that the

institution I wanted to approach first was the National Library of

Ireland, because I thought it belonged there'. In contrast, she was

quoted earlier in the Sunday

Times, Irish Edition, of 7 May

2006:

'There were multiple balls in the air. To suggest I knew the National

Library would buy it is a pipe dream. Nobody could know that.' Ms

Barnes is

also quoted in the Irish Times of 15 June 2006, 'I wasn't trying to

hide anything'. The Finnegans

Wake manuscripts sale contract of

June 2005

contains a confidentiality clause which prevented the National Library

from releasing her name unless legally obliged to do so, and as already noted, in

February 2006 her agent Sotheby’s informed National Library

Director Ó hAonghusa that ‘she would obviously prefer

it if

her name did

not come out at all’.

The affair unexpectedly came back

into public view in late 2006, arising from Dáil questions put

down by opposition Fine Gael Party representative Paul McGrath in

December. McGrath asked Arts Minister O'Donoghue about the purchase of

the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts, and sought details of consultancy payments to Laura

Barnes. Remarkably, and before the Minister had actually answered the

questions, McGrath received an early morning phone call from Ms Barnes,

who objected to what she claimed were personal questions, and

reportedly also threatened legal action. McGrath lodged a formal

complaint with the Ceann Comhairle of the Dáil, seeking to

establish if there has been any breach of protocol in relation to the

handling of his questions by the Arts Department. In mid-January 2007 a

Sunday newspaper raised further concerns over a possible conflict

of interest arising from Ms Barnes's personal relationship with an

Assistant Secretary General in the Arts Department, Niall Ó

Donnchú. The upshot is that Minister O'Donoghue ordered

a departmental enquiry into the purchase of the Finnegans Wake manuscripts, and

the affair was also referred to the Comptroller

and Auditor General and the Oireachtas Committee on Procedure and

Privilege. (24)

The Joyce Estate has been

embroiled in a major legal battle arising from an attempt by Professor

Carol Loeb Shloss, a biographer of Joyce's troubled daughter Lucia, to

reverse refusal of permission to cite certain manuscripts whose

copyright remains in the possession of the Estate. (25) In a settlement

agreed with the Estate in March 2007, Shloss 'won the right to publish

her scholarship on the literary work of James Joyce online and in

print'. (26) One may

sympathise with a scholar who wishes to cite sources without

restriction in order to support an argument, whether or not one agrees

with their conclusions. However, all the interests endeavouring to

wrest control of an extremely valuable commodity from the Joyce Estate

may not be entirely pure in their motivations. Certainly, the

mysterious not to say murky circumstances in which Joycean manuscripts

of doubtful provenance have been traded in recent years at inflated

prices continues to be a cause of concern. Having reviewed some recent

Joycean commentaries, the writer also wonders how intellectually

honest it is to give extensive coverage to the Shloss suit while

remaining mute about the ongoing controversy surrounding the Finnegans Wake manuscripts?

At this stage the writer admits

that it is just not possible to connect all the contradictory dots in

relation to the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts purchased in 2005

by the

National Library of Ireland

from Laura Barnes, aka

Rosenfeld, aka Weldon. Furthermore the picture remains blurred in regard to the earlier cache of Joycean

manuscripts acquired in 2002 from Alexis Léon. Since 2000 the

National Library has spent approximately €15 million of public funds acquiring manuscripts of James Joyce. Such a

large expenditure on literary manuscripts requires the highest levels

of transparency and accountability, and it is not acceptable that

questions should remain unanswered with regard to provenance

and cost, as well as relations between a vendor and National

Library staff.

As Bloomsday was officially

expanded to 'Bloomsweek' in June 2007, the Department of Arts enquiry into the Finnegans Wake manuscripts

acquisition was believed to have been largely completed although still to be

published, and there were increasing difficulties obtaining documents

under

the Freedom of Information Acts. However, one interesting document

which the writer did receive as a result of repeated FOI requests is an

invoice dated 3 August 2004, from Ms Laura Weldon, aka Barnes, to the

National Library of Ireland, in respect of a Joycean postcard purchased

on its behalf at a Sotheby's sale in London on 8 July 2004. It would be

reasonable to state that this document shows that Ms Barnes was acting

as an agent of the National Library during this period, and to ask

whether it might have been advisable for her to step aside from the

purchase of the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts, in order to allow the Library to acquire them under the

most advantageous and cost effective terms.

Invoice to National Library of Ireland 2004 (FOI release 2 July 2007)

In November 2007 the Department of Arts report into

the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts affair, compiled by former Secretary General Philip

Furlong, was at last released by Minister Séamus Brennan.

Furlong exonerated Laura Barnes (and Niall Ó Donnchú),

stating that all the available evidence 'offers overwhelming support

for the proposition that her acquisition of the Finnegan's (sic) Wake manuscripts was a genuinely

arms-length transaction'. Yet it was conceded that the phone call to

Paul McGrath constituted 'an unacceptable intrusion on the exercise of

a core responsibility of the Dáil Deputy'. Unfortunately,

there are certain serious flaws in the Furlong report.

For example, Mr Furlong did not interview the Joycean expert Danis Rose

in relation to his statement that he alerted Luca Crispi of the

National Library to the availability of the mansucripts at a lower

price early in 2004 (see copy of Rose's letter dated 27 March 2006 obtained via a Freedom of Information application). Mr Furlong rather glosses over Ms Barnes’s

status as an agent and advisor of the National Library, then overseen

by the Arts Department, when she acquired the Finnegans Wake manuscripts in

2004, and most surprisingly he omits to list the above illustrated

invoice in a table of payments to Ms Barnes appended to his report. The

Furlong report also includes a claim that Ms Barnes did not as hitherto

indicated acquire the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts in December 2004, when her Arts Department contract had

terminated, but rather that she entered into an agreement with Mr Vrain

to purchase the manuscripts as early as 28 April 2004, when her

contract was still very much operative. (27)

In April 2008 a further report on the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts affair was issued by the Comptroller and Auditor

General, the State's public expenditure overseer. The Comptroller

firstly reviewed the process by which the National Library came to

acquire the manuscripts in 2005, basing his account primarily on the

contents of the Furlong report. The Comptroller accepted that the

Library 'obtained the manuscripts at market value', but did indicate

that they may have originally have been on offer by their French owner

at considerably less cost. The Comptroller took account as well of

the fact that the vendor Ms Barnes had also acted as an agent of the

National Library, listing the above mentioned July 2004 transaction

overlooked by Furlong. While the Comptroller found that Ms Barnes's

purchase of the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts did not appear to 'explicitly contravene' the terms of

her contract with the Arts Department, nevertheless 'it would have been

clear to informed members of the Joycean community that the Library

would have been particularly interested in acquiring the manuscripts to

supplement its collection of Joycean material purchased for €13.5

million between 2000 and 2004, since those purchases had been widely

publicised'. The Comptroller

concluded by observing that while the State ultimately acquired the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts at market value, 'the circumstances surrounding the

sourcing of the material and the level of interaction that is

inevitable within a limited community of persons in a specialised field

strongly suggests that more robust contractual and ethical arrangements

may be required to protect the State's interests where such factors

come into play'. (28)

The

Comptroller's report was considered by the Public Accounts Committee on

9 October 2008, and was the subject of an Irish Times article the following day. Members of the Committee were reported to

have expressed concern that there had been 'collusion' between Arts

Department and National Library staff, and that the Finnegans Wake

purchase represented bad value for money, in that the collection had

been available for one-third the final price of €1.17 million a year

earlier. Committee Chairman Bernard Allen TD was quoted as stating that

there was evidence of a 'serious sting', while Tommy Broughan TD

referred to 'sharp practice', going on to identify for the record the

former National Library employee as Luca Crispi and the former Arts

Department employee as Laura Barnes. Jim O'Keeffe TD asked why 'the

price of a Rynair flight was not spent sending someone to check out if

the €400,000 price was correct'. National Library Director Aongus Ó

hAonghusa was in attendance as the committee deliberated, and defended

his institution's conduct of the deal, declining to make any apologies

and claiming 'our hands were already full . . . we didn't have the

staff resources'. (29)

Legal proceedings were commenced in the High Court against a blogger 'Ardmayle' who commented on the Finnegans Wake

manuscripts affair in 2007,

even though he removed the comments and apologised unreservedly.

(30) In January 2010 it was reported that 'Ardmayle' had agreed to pay

€100,000 damages in a settlement, and it was noted that the cost of

defending the case in a full court trial would be in the region of

€700,000-800,000, (31) coincidentally not far off the amount of profit

believed to have been made from the sale of the Finnegans Wake manuscripts. For his part the present writer feels obliged to reiterate that he has raised

issues of public concern and has put certain

questions to the principals involved in the Finnegans Wake manuscripts

transaction which they have declined to

answer. At all stages I am ready to correct any demonstrably

incorrect statements on my webpages, for the content of which I alone

am responsible.

However, it remains the case that of all the recent aquisitions of Joycean manuscripts, the Finnegans Wake

transaction remains the most troubling in terms of the provenance of

the material, the ethical blurring of the lines of private and public

interest in the case of contracted state employees, and the sheer size

of the €700,000 profit made by one individual at public expense. To put

the matter further in perspective, the said profit represents nearly 6%

of the

National Library's total allocation from public funds of €12 million in

2008, a matter rendered even more serious by the sudden collapse in

state revenues as Ireland's economic miracle proved to be based on

reckless banking practices and an unsustainable property bubble.

Finally,

it remains to be seen whether there are more discoveries of

lucrative caches of Joycean manuscripts of uncertain

provenance waiting to be discovered, will additional early Finnegans

Wake

material resurface, have the sources now

been

exhausted, or more pertinently, will the ending of the profligate

expenditure which characterised Celtic Tiger Ireland make the lucrative

Joycean transactions we have been describing a thing of the past?

Sean J Murphy

Commenced Bloomsday 2003, last revised 21 January 2012

References

(1) Louis Armand, 'From

Hypertext

to Vortext: Notes on Materiality and Language', Hypermedia

Joyce Studies, 4, Issue 2,

2003-4, http://www.geocities.com/hypermedia_joyce/armand4.html.

(2) Irish

Times, 15

December 2000.

(3) Same, 13 July 2001;

Phoenix, 31 August 2001.

(4) Irish

Times, 31 May

2002.

(5) Catherine Fahy, The

James

Joyce-Paul Léon Papers in the National Library of Ireland: A

Catalogue, Dublin 1992.

(6) Statement of

Professor Michael

Groden, 30 May 2002; National Library of Ireland, News

Extra,

Summer 2002.

(7) 'Genuinely thrilling

Joyce-news', posting to alt.books.james-joyce, rec.arts.books, 31

May 2002.

(8) FOI Request Manager,

National

Library of Ireland, to author, 17 October 2002.

(9) Phoenix,

14 March

2003.

(10) The National

Library has also

placed a detailed listing of the Joyce Papers 2002 on its website

at http://www.nli.ie/.

(11) Susan Hood, Royal

Roots,

Republican Inheritance: The Survival of the Office of Arms,

Dublin 2002, page vii.

(12) Lucie Noel, James

Joyce

and Paul Léon: The Story of a Friendship,

New York 1950,

pages 36-40, 52.

(13) Last Will and

Testament of

James Joyce, 5 August 1931, Probate Office copy 2004; Phoenix,

16 July 2004; Sunday Business

Post, 5 October 2003.

(14) Copyright and

Related Rights

(Amendment) Bill 2004, http://www.oireachtas.ie/viewdoc.asp?fn=/documents/bills28/bills/2004/2004/document1.htm.

(15) National

Library of Ireland, New

Joyce

manuscript accession

March 2006, http://www.nli.ie/new_news.htm

(press release). The

title of Joyce's novel,

although not in fact a great deal of its bewildering content, was

inspired

by an American music hall ballad written by one John F Poole (Jane S

Meehan, 'Tim Finigan's Wake', A Wake

Newslitter, 13, no 4, 1976, pages 69-73).

(16) Phoenix,

10 and

24 March 2006.

(17) Phoenix,

5 May 2006, and Sunday

Times, Irish Edition, 7

May 2006.

(18) National Library of

Ireland, Contract 28 June 2005 and other FOI releases in relation to Finnegans

Wake manuscripts acquisition.

(19) 'Rare Joyce papers

delay cost €800k', Sunday

Independent, 21 May 2006.

(20) Luca Crispi to Aongus

Ó hAonghusa, e-mail 5 May 2005, NLI FOI release.

(21) Phoenix,

2 June 2006.

(22) E-mails and letters to

Aongus Ó hAonghusa, Luca Crispi and Laura Barnes, April-June

2006, unacknowledged or refusal to reply to points raised.

(23) 'A business head on

Joyce shoulders', Irish Times,

15 June 2006.

(24) 'Conflict of Interest?', Irish

Mail on Sunday, 14 January 2007; Phoenix, 26 January 2007.

(25) D T Max, 'The Injustice Collector: Is James Joyce's grandson

suppressing scholarship?', New Yorker,

19 June 2006, http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content/articles/060619fa_fact.

(26) 'Stanford Scholar Wins Right to Publish Joyce Material', http://www.law.stanford.edu/news/pr/55/.

(27) Phoenix, 14 December

2007.

(28) Comptroller and Auditor General, Special Report: General Matters Arising on Audits, April 2008, http://audgen.gov.ie/viewdoc.asp?DocID=1100.

(29) Irish Times, 10 October 2008; the full transcript of the Public Accounts Committee debate on 9 October 2008 can be read at http://debates.oireachtas.ie/DDebate.aspx?F=ACC20081009.xml&Node=H4&Page=3.

(30) 'Apology', 13 February 2007, http://ardmayle.blogspot.com/2007/02/apology.html;

'Blooming Joyceans', Phoenix,

15 July 2007.

(31) 'Blogger must pay €100,000 for libel', Sunday Times, Irish Edition, 1 February 2010, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/ireland/article7009820.ece.