Irish Historical Mysteries: The MacCarthy Mór Hoax

Terence

MacCarthy 'Mór' (right) with President Mary Robinson

and Mr Nicholas Robinson, Cashel 1996

Ireland currently has a series of official tribunals enquiring into corruption in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly in relation to payments to politicians and perversion of the planning processs. It would appear that 'The times that were in it', as the saying goes, permitted the wealthy and powerful to circumvent normal procedures and controls in order to further their own interests. Now genealogy may be comparatively small beer in the general scheme of things, but it too has suffered from the decline in standards which has afflicted so many areas of Irish life. Ireland has been transformed from the underdeveloped but friendly society which so charmed visitors, to the roaring 'Celtic Tiger' where making a buck is the bottom line and values do not rise above the merely monetary. On the face of it, the above picture represents the happy co-existence of the old Ireland and the new Ireland: a Gaelic Chief posing side by side with the President of the Irish Republic. Alas, we shall see that all was not as it appeared.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s the present writer was still struggling to establish himself as a professional genealogist and educationalist, but he could see that all was not well in the business of roots tracing. It was clear that demand for genealogical services, particularly from descendants of Irish emigrants abroad, was on the increase, but Government and relevant authorities were not acting to improve facilities for research or to support the training of competent professionals. The writer made his views about standards known to all and sundry, including the President of Ireland, government ministers, opposition politicians, civil servants, tourism executives, academics, librarians, archivists, fellow professional genealogists, but to little or no avail.

One area which caused the writer particular concern was that of spurious 'Clans' and bogus 'Chiefs'. In the first place, as Edward MacLysaght and other authorities were at pains to point out, Ireland never had a clan system like that of Scotland, and MacLysaght advised that the term 'sept' is more appropriate in the Irish context. (1) In the second place, the thorough destruction by the English of Gaelic political structures in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, allied with the loss of so many Irish records over the centuries, mean that only a handful of families can truly trace their lineages back to a duly inaugurated Chief. Nevertheless, Government and tourism interests required that Irish 'Clan' organisations should be brought into being, and that new 'Chiefs' should be found. Thus although it regularly pleaded lack of resources adequate to perform basic genealogical tasks, in 1989 the State's Genealogical Office/Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland found space in its new premises in Kildare Street, Dublin, for the organisation known as the 'Clans of Ireland'. It would be fair to say that most Irish genealogists acquiesced in the face of this tourism-driven 'clansterism', or indeed actively supported it. (2) For his pains in opposing the march of pseudo-genealogy and pseudo-heraldry and attempting to assert some kind of standards, the writer found himself isolated from most of his professional colleagues and effectively barred from contract work in the Genealogical Office from 1993.

Some fifteen Chiefs of the Name had been afforded courtesy recognition by the State in 1944-45, primarily on the initiative of Edward MacLyaght, the first Irish Chief Herald and administrator of the Genealogical Office. (3) These were MacDermott, MacGillycuddy, O Callaghan, O Conor Don, O Donoghue, O Donovan, O Morchoe, O Neill, Fox, O Toole, O Grady, O Kelly, O Brien, MacMurrough Kavanagh, O Donnell. MacLysaght had the lineages of these Chiefs checked carefully, accompanying his acceptance with reservations in some cases, and indeed there were a few claimants to chiefly titles who were not accepted on grounds of lack of genealogical evidence. MacLysaght's criterion of recognition was based on an applicant being able to prove primogenitural or senior male line descent from the last inaugurated Chief.

MacLysaght's was not a perfect system, but at least it served to sort out those who had properly documented pedigrees from those who had not, and provided a means of affording the courtesy of recognition to the senior representatives of old Gaelic families, consistent with our republican system. Certainly, there was no practical possibility of reviving the Gaelic system of Tanistry, whereby the decision on appointing a new Chief supposedly was made collectively by the derbfine, or male descendants of a common great-grandfather. In any case, scholars are increasingly indicating that so-called Tanistry is a retrospective attempt to simplify a much more complex reality, where seniority in the dominant kingroup, political skill and military strength were all in play in deciding succession to kingships and chiefships. (4) But after MacLysaght's passing from the scene, the Office of the Chief Herald ceased to trouble itself with such academic niceties. In or about 1989, the then Chief Herald Donal Begley decided to begin a process of recognising additional Chiefs, and between that year and 1995 seven new Chiefs were recognised, namely, O Doherty, O Long, Maguire, MacCarthy Mór, O Carroll, O Rourke, MacDonnell. (5) In time it would become clear that not all these new additions to the list of recognised Chiefs had been evaluated with the same care as those approved by MacLysaght, and that in some cases, the criterion of primogenitural descent had been abandoned in favour of what we might call pseudo-Tanistry, or indeed outright genealogical fabrication.

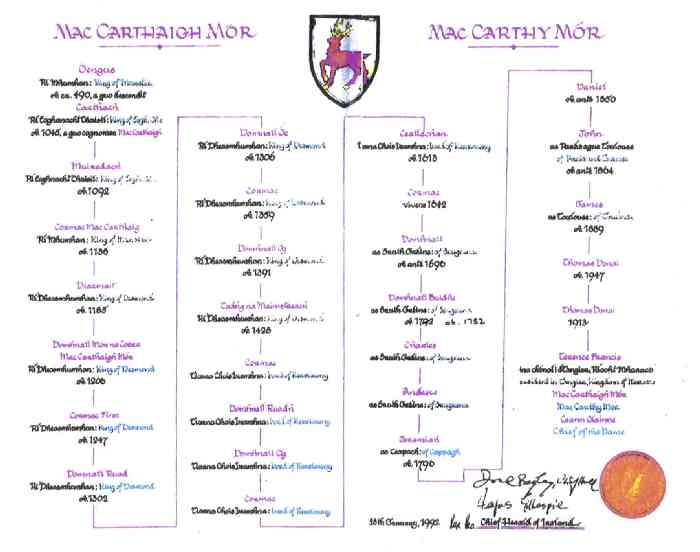

1992

Certificate recognising Terence MacCarthy as MacCarthy Mór,

signed by Chief Herald and Deputy Chief Herald

Of the newly recognised Chiefs, the one who attracted the most attention and publicity was Terence Francis MacCarthy, styled The MacCarthy Mór, Prince of Desmond. Born in Belfast in 1957 and a graduate of Queen's University in that city, MacCarthy presented via voluminous publications and a large Internet site what appeared at first sight to be an unassailable array of genealogical, heraldic, historical and juridical data in support of his claims. Not only was he Chief of the MacCarthy Clan, but also a Royal Prince of Munster with the power to bestow titles and honours, and all this with the approval of the Irish State. Indeed, in 1996 MacCarthy succeeded in having himself photographed with President Mary Robinson and her husband, to which memorable image we have already referred. MacCarthy also managed to persuade the Cashel Heritage Centre to incorporate in its displays a case containing 'Heirlooms' of his family, which tourism interests promoted as a 'must see' attraction. As a result of a civil action taken by MacCarthy against a certain Dr Marco Horak, an Italian court in Casale Monferrato issued judgments in 1998 in favour of MacCarthy's right to use royal arms, bestow titles and confer the Order of the Niadh Nask. (6) MacCarthy's supporters also included the well-known author Peter Berresford Ellis, who published a book in 1999 containing a foreword by and eulogistic coverage of MacCarthy. (7)

The website maintained on MacCarthy's behalf listed a dazzling array of titles and decorations: Headship of the Eóghanacht Royal House of Munster, Grand Officer of the Royal Albanian Order of Scanderbeg ('conferred by His Majesty King Leka I of the Albanians'), Knight of Justice of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George of Naples, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Seal of Solomon, and so on. In addition, MacCarthy publicised his personal dynastic order, the Niadh Nask, which he claimed had existed for centuries. The membership roll of the Niadh Nask included two former Irish Prime Ministers, Haughey and Reynolds, a number of Irish Chiefs, Peter Berresford Ellis, the academic Dr Katherine Simms, two former American state governors, an Assistant Secretary General of the United Nations, and General William Westmoreland. In all about 450 individuals, mostly Americans, were persuaded to join, those who were not admitted gratis on account of their prestige paying a fee of $850. The titles of lordship sold by MacCarthy ranged in price from $6,000 to $20,000, and an undetermined number of these, perhaps up to 20, were disposed of. There were also 'charitable appeals', sale of books and regalia, as well as subventions towards travel and accomodation, so that the total revenues raised by the MacCarthy Mór enterprise may have been in the region of $1,000,000.

Because he had been removed from professional work in the Genealogical Office and had trouble accessing its records, the writer's doubts about the propriety of developments relating to Chiefs took some time to crystallise and initially had to remain untested. Yet the writer's general concerns over the manner in which the Genealogical Office was being administered were to a considerable extent vindicated by the early retirement of the Chief Herald in June 1995. Across the Irish Sea, the College of Arms in London had been thrown into turmoil the previous month by the retirement of Garter King of Arms Sir Conrad Swan, following allegations of serious irregularities in relation to a grant of arms to his son-in-law. National Library of Ireland Director Dr Patricia Donlon was appointed as the new Chief Herald of Ireland, and one consequence was the lifting of an effective embargo on the writer's employment as a consultant. Despite resistance by vested interests, a process of fully integrating the Genealogical Office into the National Library of Ireland was begun by Dr Donlon. However, following Dr Donlon's retirement in 1997, the writer found himself frozen out once again.

Fortunately, one important reform instituted by Dr Donlon could never be completely overthrown, namely, improved access to the manuscript holdings of the Genealogical Office, including those relating to the recognition of new Chiefs. For the first time in his career, the writer began to understand better the compact but important range of records held by the Genealogical Office, and from 1995 onwards he spent many hours viewing them in the Manuscripts Reading Room of the National Library of Ireland, situated above the Genealogical Office in Kildare Street. The contrast in record keeping beween MacLysaght and his successors soon became painfully clear, but more than that, doubts concerning the authenticity of certain recognised Chiefs soon began to be converted into a belief that they might in fact be bogus.

The case of MacCarthy Mór seemed to be the most problematic, and indeed by 1998 if not before, the ever-active genealogical grapevine in Ireland was buzzing with allegations that all was not well with his pedigree, and anonymous papers had begun to circulate. Some, including the writer and others mostly located abroad, preferred to confront the issue more directly, and in particular serious questions began to be raised on the Internet Newsgroup rec.heraldry. One irregularity was that Terence MacCarthy was the second son of a living father who had 'abdicated'. Terence MacCarthy justified this by rejecting MacLysaght's primogenitural requirement and insisting that he acquired the title through 'Tanistry', claiming that his grandfather was appointed Chief by a 'Pact de Famille' in Nantes in 1905. As he approached closer to the truth, the writer began to experience renewed difficulties in accessing Genealogical Office manuscripts in a timely and convenient manner, so much so that he had to appeal to the Office of the Ombudsman. Notwithstanding obstructions, it was eventually established that the Genealogical Office had accepted MacCarthy's fabulous pedigree descending from Aongus, King of Munster in the fifth century, through Carthach in the eleventh century, down to his grandfather Thomas Donal, allegedly appointed MacCarthy Mór by the 'Pacte de Famille' of 1905, continuing with his father, also Thomas Donal, who 'abdicated' in 1980, and concluding with the great man himself, who allegedly 'succeeded' his father in 1980. (8)

In fact, MacCarthy's pedigree, as researched by the present writer and others, is much plainer:

Bernard MacCarthy

m Mary -

d pre-1876

|

James MacCarthy/MacCartney

b c1853, labourer, dealer

m Mary Anne Early 15 May 1876 Belfast

d 11 June 1889 Belfast

|

Thomas MacCarthy/MacCartney

b 15 February 1880 Belfast, labourer, soldier

m Anne Major, mill worker, 26 February 1906 Belfast

d 26 December 1943 Belfast

|

Thomas Daniel MacCarthy

b 29 May 1913 Belfast, professional dancer

m Harriet Maguire, typist, 20 July 1955 Belfast

styled MacCarthy Mór until 'abdication' 1980

|

Terence Francis MacCarthy

b 21 January 1957 Belfast, resident in Tangier, Morocco

styled MacCarthy Mór until 'abdication' 1999 (9)

It would not be unjust to observe that the two versions of the pedigree give radically different impressions, MacCarthy's account painting a picture of a genteel, primarily French-domiciled family, with no hint of any Belfast connection. The second and properly documented account conveys an image of a Belfast-based family of modest means and only recent aristocratic pretensions. Additionally, MacCarthy has persistently misstated the name of his great-great-grandfather as John instead of Bernard, and the date of death of his grandfather as 1947 instead of 1943. Furthermore, many if not most Ulster MacCarthys are really MacCartneys in disguise, as MacCarthy was used as a synonym of the latter surname. (10) The fact that Terence MacCarthy's grandfather was registered as a MacCartney at birth would tend to confirm that his family were of this stock, and were not connected either with the Munster MacCarthys or any French emigré branches.

By the summer of 1999 it seemed to the present writer that the MacCarthy Mór farce had gone on long enough, that fear or cynicism seemed to have paralysed most of those Irish genealogists who knew what was going on, and that the Office of the Chief Herald in particular would take no action unless prodded. Hence the writer completed a report on the affair on 16 June 1999, signed his name to it and put it in circulation. (11) As it happened, the Irish Office of the Sunday Times had also been making its own enquiries into the MacCarthy Mór affair, and on 20 June 1999 the Irish edition of the paper contained a memorable and hard-hitting article by John Burns entitled 'Irish Clan Chief's reign may be over', which laid bare the basic facts of the case and cited the writer's report. The article also revealed that Terence MacCarthy's close associate Andrew Davison, the so-called Count of Clandermond, had been sentenced to two years' imprisonment for blackmail in Northern Ireland in 1986, and that MacCarthy's elder brother had died in the course of an Irish National Liberation Army feud in 1987. MacCarthy and Davison were living in royal style in Tangier, Morocco, and if any stories concerning their colourful pasts found their way to that exotic location, it does not appear that the authorities or the expatriate community there paid much heed to them.

Events moved swiftly after the issuing of the writer's report and the Sunday Times exposé, and on 19 July 1999 Chief Herald O Donoghue issued a statement declaring that: '(i) the 1992 decision to grant courtesy recognition to Mr McCarthy as MacCarthy Mór is to be regarded as null and void; (ii) the decision in 1979 to ratify and confirm arms to Mr McCarthy must be regarded as invalid; and (iii) the pedigree registered for Mr McCarthy in 1980 is without genealogical integrity.' It later emerged that the Office of the Chief Herald had been in possession of most of the facts relating to MacCarthy for some time, begging the question as to why action had been so long delayed, and indeed rendering implausible the claim that the timing of its action was uninfluenced by the writer's report.

As some critics of Terence MacCarthy's royal pretensions had already received threats of legal action, the writer braced himself for the inevitable backlash, which in the event took a perhaps unexpected form. MacCarthy's large retinue of devoted courtiers included a group known as the Royal Eóghanacht Galloglas Guard, members of which had taken an oath of loyalty to their royal master. On 20 July 1999 the Galloglas Guard issued a statement, published on the Internet against an ominous black background, which promised that its 'G2 Branch', ie, intelligence division, would place the present writer, staff of the Genealogical Office and of the Sunday Times under surveillance.While we can laugh at the absurdity of all of this now, a threat from a paramilitary group connected to a Belfast personage always needs to be taken seriously, and indeed Chief Herald O Donoghue felt it necessary to call in the police. The present writer also took certain security precautions, and in the months following he slept very lightly indeed, fancying several times that he could hear the sound of Galloglas warpipes advancing through the furze and heather on Bray Head! It is also ironic that the abuse emanating from the Office of the Chief Herald was even more venomous than that of the MacCarthyites, so that for example, in a letter dated 5 July 1999 the Chief Herald himself derided the writer as 'the self-appointed saviour of Irish genealogy' and spoke of 'his extravagant claims, his attempts at self-promotion'.

After a period of denial, most of Terence MacCarthy's supporters came to accept the truth that his pedigree and titular claims had been fabricated. Peter Berresford Ellis, Dr Patrick O'Shea and other leading courtiers publicly renounced their former champion, while David Wooten, who had published many of MacCarthy's books through his Gryfons Publishers imprint, admitted ruefully that he was 'among hundreds duped by one of the greatest con men of this century'. The MacCarthy 'Heirlooms' were quietly removed from Cashel Heritage Centre and eventually returned to MacCarthy's representatives. As the Cyber-Kingdom of Desmond collapsed in ruins, MacCarthy's website was dismantled, and the threatening Galloglas Guard notice disappeared. Members of MacCarthy's main power base, the Niadh Nask Order, met in solemn conclave in Atlanta, Georgia, and on 2 October 1999 withdrew support, effectively delivering an ultimatum to MacCarthy that he should resign as Chief within a week. On 9 October 1999 MacCarthy bowed to the inevitable and 'abdicated' as MacCarthy Mór, citing loss of support but not admitting any guilt or wrongdoing.

What is it exactly that drove Terence MacCarthy to perpetrate such an outrageous hoax? Perhaps like Patricia Highsmith's character the Talented Mr Ripley, he thought it would be better to be 'a fake somebody than a real nobody'. The tragedy of the affair is that MacCarthy is clearly a genealogist and heraldist of some ability, but he chose to deploy his talents to take advantage of those in Ireland and abroad whose enthusiasm for Irish heritage was alas greater than their knowledge of same. In February 2000 a brother of MacCarthy, Conor, made a claim to have 'succeeded' as MacCarthy Mór, but this has largely been greeted with derision and is of course equally baseless. The writer has also established that Terence MacCarthy was not the only bogus Chief recognised by the Office of the Chief Herald in the period 1989-95, as the pedigrees of Maguire and O Long are also essentially fabricated, and there are serious questions concerning other recognitions. The Minister for Arts and Heritage promised in September 1999 to establish a committee to review procedures for granting courtesy recognition to Chiefs, but no such review body has been established, and the current official position has been that certain unspecified 'legal issues' raised by Maguire's solicitor mean that no action can be taken. (12)

Despite the relatively limited concern evidenced in Ireland, there is no doubt that the MacCarthy Mór Hoax is the most brazen and extensive of its kind ever to be mounted in this country, and it has caused untold damage to the reputation of Irish genealogy and heraldry internationally. The writer has spent hundreds of hours investigating the MacCarthy case, in the face of obstruction, abuse and threats both legal and otherwise, but he finds that there are still some unsolved mysteries and unanswered questions relating to the affair. The most serious and indeed the most puzzling aspect of the scandal has been the fact that the Office of the Chief Herald/Genealogical Office actually validated the hoax in 1992, ignoring warnings concerning declining standards given by the present writer, and, it has now been established, specific warnings from others concerning MacCarthy. There is of course an unanswerable case for the MacCarthy Mór and associated bogus Chiefs scandals to be made the subject of a thorough official enquiry, and if found necessary, to follow through with appropriate legal proceedings.

There are remarkable parallels between the MacCarthy Mór Hoax and the 1907 Irish Crown Jewels Affair (chronicled elsewhere on this site), as in both episodes a State office dealing with heraldry and genealogy was infiltrated by undesirable elements and used as a theatre of corruption and illegality, in the one case fraud and in the other theft. In July 2003 the Office of the Chief Herald 'solved' the chiefs problem by the simple expedient of terminating the system of courtesy recognition, walking away from its responsibilities, dumping chiefs both good and bad and leaving corrupt records of spurious pedigrees, arms and titles uncorrected. (13) National Library Director/Chief Herald O Donoghue retired in September 2003, and while a new Director was apointed, the post of Chief Herald remained vacant for two years due to fall-out from the Mac Carthy Mór affair, until in August 2005 former Deputy Chief Herald Gillespie was appointed to the position. Visitors to the State Heraldic Museum in Kildare Street, Dublin, can view a display case relating to the Crown Jewels Affair, and while unsurprisingly there is no similar official commemoration of the current scandal, if they cast their eyes upwards they may spot the vacant spaces on the walls where hung until recently the banners of the disgraced MacCarthy Mór and the other recognised chiefs. As to Terence MacCarthy's circumstances today, we learn from humorous author Pete McCarthy's latest bestseller that he still resides in Tangier with his partner Andrew Davison, in a 'pink-walled villa' on a hillside on the outskirts of the city. (14) The effects of the Mac Carthy Mór hoax will be felt for many years to come, and as yet there is little apparent realisation of the need to remedy the problem of abysmally low standards in Irish genealogy and heraldry which facilitated its progress.

Sean Murphy

References

(1) Edward MacLysaght, Irish Families, Irish Academic Press, Dublin 1985 Edition, page 12.

(2) John Grenham, Clans and Families of Ireland, Gill and Macmillan, Dublin 1993, and The Little Book of Irish Clans, John Hinde Ltd, Dublin 1994; Ida Grehan, Irish Family Histories, Town House, Dublin 1993.

(3) Edward MacLysaght, More Irish Families, Irish Academic Press, Dublin 1982 Edition, pages 15-20.

(4) See for example Donnchadh Ó Corráin, 'Irish Regnal Succession: a Reappraisal', Studia Hibernica, 11, 1971, pages 7-39.

(5) Register of Chiefs, Genealogical Office MS 627.

(6) A New Book of Rights, Royal Eóghanacht Society, Clonmel 1998, passim.

(7) Peter Berresford Ellis, Erin's Blood Royal: The Gaelic Noble Dynasties of Ireland, Constable, London 1999, Foreword by Terence MacCarthy, pages 1-7; a 'revised' edition of this work was published by Palgrave, New York, in 2002, in which the author concedes that MacCarthy was an impostor, but continues to promote so-called 'Tanistry'.

(8) Commentary to Samuel Trant MacCarthy Mór, The MacCarthys of Munster, Facsimile Edition, Gryfons Publishers, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1997, pages 521-24. Other publications by Terence MacCarthy, some co-edited or co-written with his associate Andrew Davison, styled the Count of Clandermond, include the following: Historical Essays on the Kingdom of Munster, Irish Genealogical Foundation, Kansas City, Missouri, 1994; Ulster's Office 1552-1800, Gryfons Publishers, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1996; An Irish Miscellany, Gryfons Publishers, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1998.

(9) Registrations of births, marriages and deaths, General Register Office, Dublin (pre-1922),and General Register Office, Belfast (post-1922); baptism and marriage certificates, St Patrick's Church, Belfast.

(10) Robert Bell, The Book of Ulster Surnames, Blackstaff Press, Belfast 1988, page 138.

(11) Sean Murphy, 'A Report on the Pedigree of Terence Francis MacCarthy, Styled the MacCarthy Mór, Prince of Desmond', 16 June 1999, published on Internet at http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/chiefs/maccarthy.htm.

(12) Reports on other bogus and questionable Chiefs and updates on developments can be found at http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/chiefs/.

(13) Sunday Times, Irish Edition, 27 July 2003.

(14) Pete McCarthy, The Road to McCarthy, Hodder and Stoughton, London 2002, page 97.