Statue of Molly Malone in seventeenth-century dress

by Jeanne Rynhart, Grafton Street, Dublin

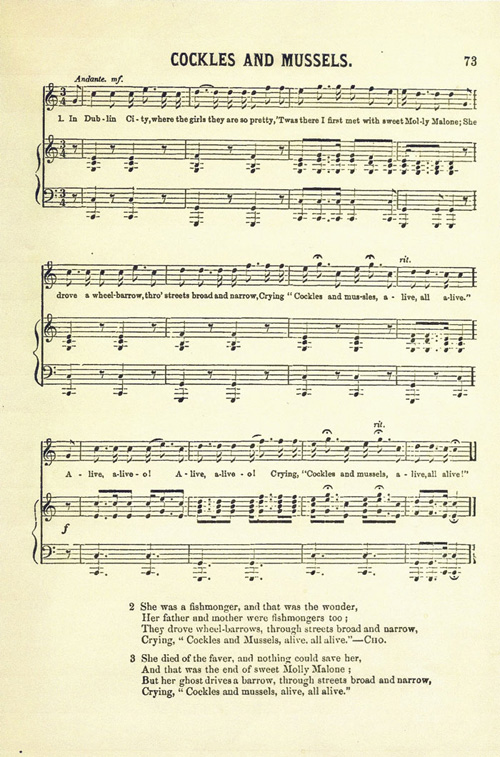

Waltons' Victorian-style image of Molly Malone

for sheet music of 'Cockles and Mussels'

Irish Historical Mysteries: Molly Malone

Statue of Molly Malone in seventeenth-century dress by Jeanne Rynhart, Grafton Street, Dublin |  Waltons' Victorian-style image of Molly Malone for sheet music of 'Cockles and Mussels' |

Reverie

As well as being known and sung internationally, the popular song 'Cockles and Mussels' has become a sort of unofficial anthem of Dublin city. The song's tragic heroine Molly Malone and her barrow have come to stand as one of the most familiar symbols of the capital. In addition, Molly's international pulling power is shown by the fact that she scores hundreds of thousands of 'hits' on the Internet, many of them relating to Irish pubs and restaurants bearing her name. It seems perfectly natural therefore that Molly should have been commemorated by erecting a statue to her in Dublin, which monument has become a familiar landmark at the end of Grafton Street. Let us now travel back in time to see what we can find out about the real Molly Malone.

Picture the scene: it is Dublin city 300 years ago, on a balmy summer evening on 12 June 1699 to be precise. The city then was not as we know it now, and in place of spacious, straight thoroughfares there was a warren of narrow, winding streets, through which it would be difficult if not impossible to drive a motor car. We walk down one of these streets on that summer e'en in 1699, when suddenly our attention is attracted by a small crowd gathered around a figure on the ground.

Moved by a mixture of curiosity and concern, we join the crowd to discover what is amiss. We see that the object of attention is a young woman, no longer of this world but with a strange look of peace on her ravaged features. She is dressed in a full-length, full-sleeved, lined chemise, an overshirt and basque of wool, and Spanish zapota shoes. Despite the pallor of death, we can see that she was a fine strong and attractive girl, with an especially well-developed bust.

'Who is it?', someone asks. 'Tis Molly Malone the fishmonger, and she is no more', replies a young lad. 'God's judgment has come upon her', adds a plump housewife, probably the lad's mother, 'for as well as her trade of fishmonger she was a part-time hussy also'.

'Be charitable and speak ye not ill of the dead, woman!', interjects another voice. We turn to identify the newcomer, and from his dress and demeanour it is clear he is a medical man, a chirurgeon or apothecary perhaps. Bending down, he examines the dead girl, and after a minute or so rises and addresses the gathering: 'If this unfortunate female has not been taken by the typhoid fever, then has she succumbed to a disease of venery, and in either case ye had better step back lest ye be contaminated by noxious vapours!'.

We disperse quickly like the rest, making our way back to our lodgings in a nearby tavern. There the talk is all of the dead Molly Malone, and of her short and tragic life. The tavern keeper informs us that Molly's parents are also in the fish-selling business, and reside near Fishamble Street, where the trade is mostly carried on. 'In a city full of pretty girls, she was one of the prettiest, and that is how she came to ply another trade as well', our host tells us sadly.

We learn that Molly had wheeled her wheel barrow from the Liberties to the more fashionable Grafton Street, crying 'Cockles and Mussels' as she went. At nights another and less admirable Molly appeared, as her chemise, basque and zapotas were replaced by an even more revealing dress, fish-net tights and stillettoes. Thus provocatively attired, she sallied forth looking for clients, who tended to include students of Trinity College, a place renowned for its debauchery. Yet, we reflect, in all probability Molly was more sinned against than sinning.

Our fascination with Molly brings us next morning to the church of St John, off Fishamble Street, where her funeral is to be held. We join her grief-stricken parents, relatives and friends as the minister begins his sermon. 'Thirty-six years ago with my own hands I baptised Molly Malone in St Andrew's Church, and today it falls to me to perform the sad duty of her obsequies', intones the parson. Having reflected on the godliness of the fish trade - 'For were not Peter and several of the Apostles fishermen?' - the minister concludes with an impassioned plea to the congregation: 'Do not judge too harshly this poor, abused Magdalene who has now herself been hauled in on the net of God's love'. Afterwards we stand discreetly at the edge of the circle of mourners as Molly's coffin is lowered into the ground in St John's Churchyard, writing the saddest and final chapter in her short life.

The years pass, but Molly is not forgotten in her native city. The ballad mongers commemorate her in a song entitled 'Cockles and Mussels', which begins, 'In Dublin's fair city, where the girls are so pretty, I first set my eyes on sweet Molly Malone'. On dusky evenings you may still hear the eerie sound of a handcart traversing Dublin's cobbled streets, wheeled 'tis said by the unquiet spirit of Molly Malone.

During Dublin's Millennium in 1988, which was held to celebrate the discovery by historical experts that the city had been founded 1,000 years before, it was decided to erect a statue of Molly. This monument now stands appropriately enough at the end of Grafton Street, around the corner from St Andrew's Church where she was baptised, and in an area where she plied her trades. A thought occurred on the 300th anniversary of her death in 1999: what better way to commemorate her than by declaring 13 June to be International Molly Malone Day, accompanied by a Molly Malone Summer School. Stand in front of Molly's statue, look into her sad eyes, see almost the tremulous heaving of her bosom, and marvel at the City of Culture where heritage is kept so alive, alive o! (1)

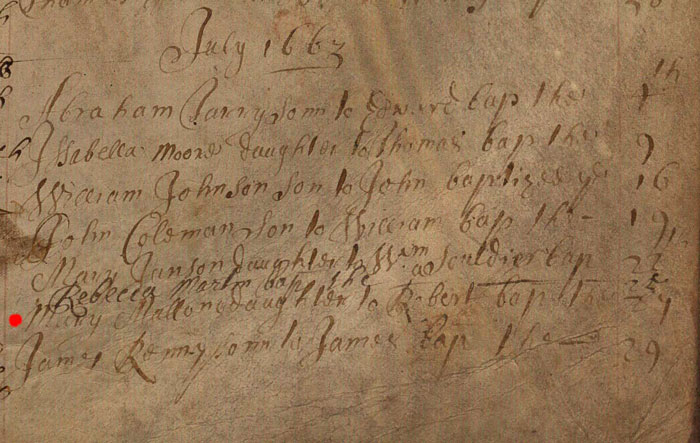

Purported baptism record of Molly Malone, 27 July 1663,

St John's Church of Ireland Parish, Dublin

The Facts

Discerning readers will have noticed by now that the substance of the above reverie is even fishier than the contents of Molly Malone's barrow. But if there are those so partial to legend and impatient of fact that they have swallowed the whole thing hook, line and sinker, then they might prefer to surf on out at this point if they wish to avoid disillusionment. Perhaps though the parody has been too broadly drawn? Not at all, as will now be demonstrated. (2)

Sometime in the last thirty years or so, a modestly anonymous individual seems to have decided without any supporting evidence that Molly Malone was a real person who lies buried in St John's Graveyard near Fishamble Street. This incipient legend was dignified by being committed to print in a serious work exposing the disgraceful destruction of the site of the Norse settlement at Wood Quay, in order to make way for new Civic Offices. (3) It is ironic that such a worthy book should have contributed to the developing Molly Malone legend, and if it was thought that a little white lie would help to protect the remnants of St John's Graveyard (also on the controversial Civic Offices site), then it was to be of no avail. In fact, Dublin Corporation bulldozed its way through the graveyard, at one point leaving human bones scattered about St John's Lane, and today there are only about six mostly cracked tombstones left on the site.

Contemporaneous with, or sometime prior to the emergence of the unsupported St John's Graveyard burial yarn, a visiting American academic apparently raised the possibility that Molly Malone might have died of typhoid fever contracted from consuming infected Dublin Bay cockles and mussels. Thus did the legend begin to grow, and it was positively to snowball during the Dublin 'Millennium' of 1988. While the title of this event gave the misleading impression that it celebrated the foundation of Dublin 1,000 years before, in fact the incident commemorated was the capture of the city by Maol Sechnaill II in 989 (not 988), as Dublin of course was founded by the Norse about 841.

The 'Millennium' thus encouraged an atmosphere where frothy fantasy could supplant historical truth, and historians and others who objected were dismissed crudely as cranks and party poopers. On 22 January 1988, at a press conference in St Andrew's Church held to launch the 'Dublin's Fair City' video show, it was solemnly announced that the baptism and burial records of Molly Malone had been discovered in the registers of St John's Church. (4) The entries in question relate to the baptism on 27 July 1663 of a Mary Mallone daughter of Robert (see image above) and to the burial of a person of the same name on 13 June 1699. St John's Church was Church of Ireland in denomination and formerly located behind Christ Church off Fishamble Street, but was demolished in the last century. St John's registers were published in 1906, the originals are held in the Representative Church Body Library and they are now conveniently also available online. (5)

While it is true that Molly is a form of the name Mary, no evidence was produced to show that the Mary or Marys listed in St John's registers were known as Molly. Furthermore, there are quite a few Mary Malone entries in the Church of Ireland baptism registers of Dublin city, with many more again in the Roman Catholic registers (which date from the eighttenth century only), and there is no logical reason to choose the St John's entries over the others. Finally, just as it was unwarranted to assume that Molly Malone was Church of Ireland and not Roman Catholic, so too was it capricious to assign her to the seventeenth instead of the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries.

Such doubts did not trouble the partisans of the evolving Molly Malone legend, and the supremo of the Dublin Millennium celebrations, Matt McNulty, decided to commission a statue of the fishmonger. The contract to sculpt the statue was won by Jeanne Rynhart, who 'researched the historical background of the statue'. The 'research' in question incorporated most of the elements of the Molly Malone legend as it then stood, but added a few new ones as well. Thus not only was Molly portrayed as a 'Restoration citizen' in seventeenth-century dress, but with blithe disregard for the poor girl's reputation, it was also claimed that she was 'a prosperous trader who freelanced as a prostitute'. More than this, Molly's 'sales path' was identified as extending from the Liberties to Grafton Street and St Stephen's Green, and it was claimed 'she would have had clients in Trinity College, which was renowned for its debauchery at the time'. Molly's statue was also clad with an extremely low-cut dress, on the grounds that as 'women breastfed publicly in Molly's time, breasts were popped out all over the place'. (6)

All this was obviously an avalanche of pure and unrestrained fantasy, but the worst blunder was yet to come. In 1989 the completed statue of Molly was placed at the junction of Grafton Street and Suffolk Street, on the stated grounds that this was around the corner from St Andrew's Church where her baptism had taken place. It will be recalled that the original version of the legend had claimed that Molly was baptised in St John's Church in 1663, while the new claim seems to have been based on nothing more than a careless reading of the newspaper account of the press conference announcing the 'discovery' of the St John's baptism entry, which conference just happened to have been held in St Andrew's Church. In any case, St Andrew's Church of Ireland parish was recreated by act of parliament in 1665 only, and its registers dating from 1672 were destroyed in 1922.

This then is the legend in all its glorious implausibilty, but what of the facts, so far as they can be ascertained? As is frequently the case with research problems of this kind, no definitive or final solution can be offered, but what has been discovered is extremely significant. In the first place, no version of 'Cockles and Mussels' predating 1850 was found, nor was it included in, for example, Colm O Lochlainn's collections of Irish ballads, (7) indicating that it does not fit the mould of a conventional traditional song. The earliest versions of 'Cockles and Mussels' complete with music which have been traced to date were published firstly in Boston, Massachusetts, in a collection of college songs in 1876, (8) secondly in another collection of student songs published in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1883 and thirdly in London in 1884 by Francis Brothers and Day. (9) While the 1876 Boston version lists no author, its inclusion in a section entitled 'Miscellaneous Songs, and English and German Student Songs' indicates that it was most likely a European import. In contrast, the 1884 London version describes the piece as a 'comic song' written and composed by James Yorkston and arranged by Edmund Forman. The latter version further acknowledges that the song was reprinted by permission of Messrs Kohler and Son of Edinburgh, so there must have been at least one earlier edition published in Scotland, which may well have been the original.

Another song entitled also 'Cockles and Mussels' was published in 1876, attibuted to the music hall singer and composer Joseph B Geoghegan, and while its lyrics contain the refrain 'Fresh cockles and mussels alive, alive o!', it is set in London, its hero is 'Jim the Mussel Man' and the melody is different. (9a) Geoghegan was a fascinating character who was born in Salford about 1816 and died in Bolton in 1889, his father James being from Dublin, and the substantial list of songs attributed to him includes originals and possible adaptations of the work of others. (9b) There is a connecting link between Yorkston and Geoghegan, in that Edmund Forman, the above mentioned arranger of the 1884 edition of 'Cockles and Mussels', also arranged a piece by Geoghegan published in 1886, entitled 'England is England still'. (9c) A London women's magazine dated 1882 featured a reply to a query about the song 'Cockles and Mussels', beginning 'For dear Dublin City, Where the girls are so pretty' and ending 'Cockles and mussels, alive O', which stated that it was 'by Mr Geoghegan, published by B Williams, 60 Paternoster Row'. (9d) While this places Geoghegan in contention for authorship, it is not impossible that his above mentioned 'Jim the Mussel Man' song was being confused with the Molly Malone version. Two variant verses of the classic song, beginning 'Twas in Dublin's sweet city, Where the girls are so pretty', have been found in the 'gagbook' of the Victorian clown Thomas Lawrence, noted as having been provided by John Gee at Cheltenham on 20 February 1871, without any attribution to a specific composer, and this is the earliest sighting of the song lyrics. (10) As indicated above, the 1876 Boston edition of 'Cockles and Mussels' currently stands as the earliest published sheet music version of the song discovered to date, and although an imperfect version in comparison to the 1884 London edition it is reproduced here for interest sake (the time signature should read 6/8 not 3/4).

Earliest sheet music version of 'Cockles and Mussels' traced

to date, published in Boston in 1876

The name 'Molly Malone' also features in the title or text of other Irish songs, the oldest discovered to date being in a volume published in Doncaster in 1790, which has been advanced as rather shaky evidence for the authenticity of the Grafton Street statue and was presented by Dublin Tourism to the Dublin Writers' Museum in 2010. This particular song is set by the 'big hill of Howth' in County Dublin, and in decidedly substandard verse the anonymous author declares his love for 'Sweet Molly Malone', making no references to cockles and mussels, Dublin City or the fish trade. (11) Referring to this song, which featured in various compilations published in the early decades of the nineteenth century, a contributor to an Edinburgh journal observed in 1831, 'Our old acquaintance Molly Malone is also redolent of the Emerald Isle'. (12) Molly Malone was clearly widely known as an Irish song character by the early decades of the nineteenth century in England and Scotland, and this could explain why the name was chosen for the heroine of the classic 'Cockles and Mussels'. Some later editions continued to attribute the song to Yorkston into the twentieth century, and indeed he is credited as the composer on the soundtrack to Kubrick's Clockwork Orange (1971). However, as the song became naturalised in Ireland the attribution of 'Cockles and Mussels' to Yorkston was generally omitted in published versions, encouraging a general assumption that it was an ancient folk song.

At this stage we are in a postion to come to some conclusions, necessarily tenatative as more information may yet come to light. It would appear that the version of 'Cockles and Mussels' sung today is not in fact 'traditional', in the sense that it does not predate the 1870s and has been credited to the Scottish-based composer James Yorkston (although as noted above Joseph B Geoghegan is another possible composer). The composer of the song may well have been influenced by earlier tunes featuring a Molly Malone, such as the 1790 piece identified above, and indeed many songwriters have borrowed themes and even lyrics and melodies from other composers and anonymous traditional ballads. It is not inconceivable that a real barrow girl in Dublin or even Edinburgh could have played a part in inspiring the composer, but it is more likely that the Molly Malone portrayed was merely a type and not an actual person. The song attributed to Yorkston was a 'comic song' replete with mock pathos, and having been performed in music halls, parlours, convivial gatherings and elsewhere it must have gained such popularity and been so widely dispersed that its origins were lost to memory and it was assumed to be just another anonymous folk song. As it was set in Dublin, obviously it would be of special interest there, and indeed in time it evolved into a sort of unofficial anthem of the city, being sung at sports and social gatherings and becoming a staple of 'traditional' ballad groups such as the Dubliners.

Before the creation of the bizarre legend that Molly Malone was a real person who lived in the seventeenth century, the writer, and no doubt many others, had an image of the fishmonger as an imaginary figure in a nineteenth-century Victorian setting. The evidence outlined above indicates that this impression is basically correct, and indeed this is the Molly Malone portrayed on the cover of Waltons' twentieth-century sheet music edition of 'Cockles and Mussels'. (12) This picture is reproduced above, and it can be seen that Molly is set amid a Victorian Dublin scene, with a silhouette of the now sadly destroyed Nelson's Pillar in the background. Compare the illustration with the adjoining photograph of the statue and note the details of Molly's dress, as well as the fact that she wheels a barrow and not a handcart as in Rynhart's sculpture.

It is submitted that this nineteenth-century image of Molly Malone, backed up by research into period details and of course an intensive study of the origin of the song 'Cockles and Mussels', would have formed a better basis for a statue of the fishmonger. Furthermore, it would have been more appropriate to site such a statue in the Moore Street area, where Molly's present-day successors, the fruit- and fish-sellers, now ply their trade, or if a more fashionable location were deemed necessary, somewhere in O'Connell Street or near the Halfpenny Bridge would have sufficed. Though it might be considered not unattractive in a quaint, kitschy sort of way, the Grafton Street sculpture of Molly nevertheless is utterly false both in its form and in its setting.

But sure what matter is it to take a few liberties with the truth, and isn't it nice to have attractive fakes when so much of the real heritage of Dublin has been destroyed? Unfortunately, there is a deadly linkage between the kind of pseudo-heritage and disregard for historical truth represented by the Molly Malone promotion, and the continuing neglect and destruction of Dublin's archaeological and architectural heritage. Faced with criticisms concerning the razing of Norse remains, the destruction of Georgian houses, the dereliction of churches or the desecration of old graveyards, the powers that be can dismiss the criticism as carping, and point for example to investment in public sculpture such as that of Molly Malone as evidence of care for heritage and culture in the city.

So entrenched has the fake legend of Molly become that there was an actual call for the commemoration of the 300th anniversary of her death in June 1999! A pair of contributors on an RTE radio programme of 7 June 1999 suggested that Molly was in fact a Dublin-born mistress of Charles II, and that cockles and mussels should be read as symbols of female genitalia! What we have here is a continuously evolving urban legend, with each new uninformed commentator compounding the errors of those who have gone before. In the course of publicity surrounding the auction of a 'spare' Molly statue head in July 2011, the sculptress Jeanne Rynhart revealed that she had originally considered that her subject was Victorian, but that purported 'new research' had caused a rethink and a move back to the seventeenth century. (13) The saddest part of the whole muddle is that what we might call the 'authentic myth' of the Victorian Molly Malone has been supplanted by a misdated, misplaced and sexually crude image concocted by heritage fabricators who exhibit complete disregard for careful historical research.

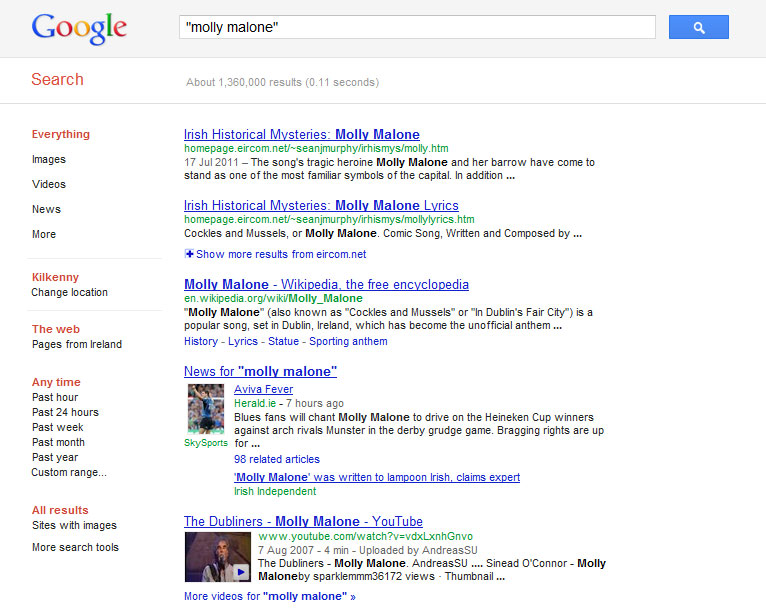

Results of Google search for 'Molly Malone' 2011

Just how internationalised Molly Malone has become is demonstrated by the fact that in 2011 a Google search for her name returned over a million hits, over 100,000 images and a couple of thousand YouTube links. Most of these relate to the Dublin statue, to lyrics, music, audio and video files of 'Cockles and Mussels', to recurring media coverage and of course to a growing empire of Molly Malone 'Irish' pubs and/or restaurants located in places as far apart as London, Glasgow, Paris, Madrid, Amsterdam, Helsinki, Stockholm, Prague, Kentucky, Los Angeles, New York, Cambodia and Singapore. In truth the Molly Malone statue is now too well established as a Dublin icon, with all that she says about our attitudes to historical fact, socialising and perhaps womanhood, to be changed, and for good or ill the 'Tart with the Cart' at the end of Grafton Street will continue to be photographed by passing tourists and to give her name to 'Irish' pubs and restaurants around the world. Never far from debate and controversy, extension works on Dublin's Luas tram system will require the temporary removal of Molly's statue from the end of Grafton Street. Some northside local politicians have taken the opportunity in 2013 to press for Molly's permanent relocation to its supposed 'rightful home' in Moore Street, where the present-day fish and fruit street traders are concentrated, although southside representatives have predictably resisted such a move. (14) While both sides show little awareness of or interest the myths and fabrication which underlie the statue of Molly Malone, its present location was based on a particularly foolish blunder, as explained above, so that a new home north of the Liffey would bring just a little more authencity to the monument. However, take a look again at Messrs Waltons' illustration above for their version of 'Cockles and Mussels', where Molly is in Victorian dress, wheeling a wheel barrow rather than a cart, and with a silhouette of the now destroyed northside monument Nelson's Pillar in the background. This is how the statue of Molly Malone should have been represented and located, but alas it was decided otherwise as we have explained in the current article.

In conclusion, it may be asked just what exactly is the Mystery of Molly Malone? In the writer's opinion, it lies in how so many supposedly intelligent people could accept uncritically the farrago of invention and misconception encapsulated in the Grafton Street statue, and to this conundrum he confesses he can offer no solution.

Sean Murphy

Last updated 16 May 2013

References

(1) Fertile imagination and ignorance of history and genealogy alike.

(2) This webpage is a development of the writer's The Mystery of Molly Malone, Dublin 1992, now out of print.

(3) John Bradley Editor, Viking Dublin exposed, Dublin 1984, page 103, where the alleged date of Molly's burial is given as 1734.

(4) Irish Times, 23 January 1988.

(5) Registers of Church of Ireland Parish of St John, Dublin, accessed 17 July 2011 via Irish Genealogy, http://www.irishgenealogy.ie/.

(6) Irish Times, 30 September 1989.

(7) Colm O Lochlainn Editor, Irish Street Ballads, Dublin 1939, and More Irish Street Ballads, Dublin 1965.

(8) 'Cockles and Mussels', in Henry R Waite, Editor, Carmina Collegensia, Boston, Massachusetts, 1876, page 73.

(8a) 'Cockles and Mussels', in William H Hills, Editor, Students' Songs, Moses King Publisher, Cambridge, Massachusetts, [1883], page 55 (reference kindly provided by Cynthia Cathcart of Silver Spring, Maryland).

(9) Cockles and Mussels, or Molly Malone, Comic Song by James Yorkston, Francis Bros & Day, London [1884]; the British Library copy is reproduced in Murphy, Mystery of Molly Malone, pages 19-24 (see note 2 above).

(9a) Cockles and Mussels, Comic Song by J B Geoghegan, H d'Alcorn & Co, London [1876], British Library, accessed at http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/vicpopmus/c/015hzz00001778ou00026001.html 4 November 2011.

(9b) 'Joseph Bryan Geoghegan, travelling singer, 1800s', The Mudcat Café, http://mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=129312, accessed 4 November 2011.

(9c) England is England Still, National Song by J B Geoghegan, Francis Bros & Day, London [1886], British Library Integrated Catalogue, http://catalogue.bl.uk/, accessed 4 November 2011.

(9d) The Ladies' Treasury, London 1882, page 237, snippet at Google Books http://books.google.ie, accessed 17 November 2011.

(10) 'Cockles and Mussels', in Jacky Bratton and Ann Featherstone, The Victorian Clown, Cambridge University Press 2006, pages 246-47, accessed at http://books.google.ie 9 July 2010.

(11) Maev Kennedy, 'Tart with a cart', Guardian, 18 July 2010, accessed at http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/jul/18/molly-malone-earliest-version-hay, 5 July 2011; same, 'Oldest known version of ballad of Molly Malone finds new home', Guardian, 11 August 2010, accessed at http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/aug/11/oldest-version-molly-malone, 4 November 2011.

(12) Review of The Shamrock: A Collection of Irish Songs, 1831, The Edinburgh Literary Journal, January-June 1831, page 43, accessed at http://books.google.ie 4 November 2011; see also 'Molly Malone', in The Pocket Encyclopedia of Scottish, English and Irish Songs, volume 2, Glasgow 1816, pages 194-95, accessed at http://books.google.ie 9 July 2010

(12) Waltons' Piano and Musical Instrument Galleries, Souvenir Album of Irish Music, Dublin, no date, possibly 1930s-50s.

(13) Interview with Jeanne Rynhart, 'Mooney', RTÉ Radio 1, 4 July 2011; Michael Parsons, 'Head of Molly Malone to go under the hammer', Irish Times, 20 June 2011, accessed at http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/ireland/2011/0620/1224299226780.html 5 July 2011.

(14) 'Sorry, Moore Street, you can't have Molly Malone', Evening Herald, 16 May 2013, accessed at http://www.herald.ie/news/sorry-moore-street-you-cant-have-molly-malone-29232503.html

16 May 2013.