|

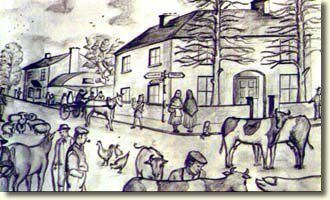

THE FAIR OF THE CROSS

-

O'DORNEY 1/12/1941 The bawling of cattle and the barking of dogs wakened him that morning. He crawled to the end of the bed and parted the curtain. It was barely light,but they were there already -cattle and men and dogs,shuffling and shouting, striking and barking, heaving and pushing, driving blindly this way and that.To him they seemed a wild and wildly exciting congregation, an invasion almost of his quiet street from some half-dark, primitive world where knuckle and horn and hoof fought savagely with fierce men for mastery of the earth. He dragged himself from the window, dressed hurriedly and ran down stairs. They had been up for some time and the fire in the kitchen stove was crackling brightly. He gobbled the breakfast he was forced to eat and reluctantly put on the black oil-cloth coat and the southwester hat that they insisted he wear. He wished that he didn't have to wear that coat and hat. They marked him out from the other lads, the lads with whom he went to school and played hurling and fished for 'kishauns'. The others didn't wear clothes like that, so why should he, just because he was the teacher's son? However, he was too eager to be gone to resist for long. As he left by the back door, he picked up the stick he had cut the day before and ran around the house and out in to the crowded street. Already it was much brighter. There was no rain so he pushed his hat onto his back, closed the gate behind him and set off down the fair towards the Cross. As he went, walking briskly in and out among the groups of cattle that were everywhere, he tried to look preoccupied, to look as if he were already employed for the day and was intent on getting to work. He reached the Cross and turned west towards the Post Office. He walked more slowly now, hoping that somebody would say, "Hey, young fella! Give us a hand with these cattle, will you?" He reached the Post Office and reached the edge of the fair at that end of the village.

He stood at a corner for a few minutes wondering what he should do next. He didn't want to go up his own road because there was always the chance that some of them from home might be coming down that way and might see him. He didn't want them to see him until he was doing something. He began to walk very slowly down the road towards the station. His hope was begining to ebb, and a kind of mild despair was lapping quietly around his heart. He went as far as the station, but nobody asked him to help them. He came slowly back and leant on the parapet on the bridge that spanned the flooded river. As he watched the muddy water race by, despair turned first to a kind of anger and then to a dull, numb loneliness. He pulled away from the mood. Maybe he could get a job if he waited another while, though by now the fair was clearly thining. Suddenly he knew what he would do, he'd have a mutton pie. Everybody had mutton pies at the fair always - well, all those who had come any distance had anyway, and he knew that they were being served that day in three or four shops in the village. He went into one of the shops and awkwardly ordered one. It cost much more than he had expected, but he had enough money and twopence to spare. The pie was placed in a dish on the counter in front of him and a mug of broth was thrown over it. He was handed a spoon and began to eat. It was awful! The pie was cold and the broth was greasy and luke warm. He tried to pretend to relish it but after a few bites he just couldn't eat any more and quickly left the shop while the proprietor wasn't looking, He went into the shop next door and bought a bar of chocolate with his twopence. Out into the steet he went again, his stick in his hand. There were even fewer cattle around now and none at all on the path where he was walking He swung his stick to hit a pebble near his feet and a man shouted "What the hell do you think you're doin' with that bloody stick, young fella? Is it the way you think I haven't enough to do without you swinging that yoke in front of the cattle! Go on off out of here now about your business, if you don't want fong where you'll feel it". Frightened and humiliated, he walked away. He saw Tom and Sean and Christy, all friends of his, driving animals, their serious faces proclaiming that here were people who had been entrusted with a grave responsibility but who were bearing it bravely and well. He mooched up and down the fair. At last he went into the Chapel, not to pray, but to get away to a place where no one would see him. When he came out the fair was almost over and he decided he would go home. He dreaded it. They'd say, "Well, how'd you get on?" or "Conas d'eirigh leat?" and he'd say - what would he say? Would he pretend that he had had a job? But they'd know. So, should he tell the truth? He tried to find the words that would make light of it, but he knew that in all the words that came to him anyone would hear his hurt, and as well as that, he was afraid that silly tears might come with the words. Just then he heard a man, "Young fella! Hey, young fella!" His heart jumped. Had he once more disturbed someone's cattle? He had almost taken to his heals when he heard the man say, "Will you give us a hand with them cattle up the road a piece?" His heart jumped again, this time with a kind of giddy joy. "Yea! all right", he said "Hup! Hup! Come on our that! How! How! the man shouted at the catttle. He helped him to turn them towards Tralee. "Bloody bad fair!" growled the man. "Oh! You didn't sell anything?" he asked timidly. "I did not, God blast it, nor sell! But I'd keep 'em until Tibb's Eve - whenever the hell that is - before I'd let 'em go at what they were offerin". They passed his own house and as they did, the boy glanced in but saw nobody. On they went, the man continually striking the rump of the animal nearest him and shouting, "How! How! Come up our that! Go on Go on! How! How!" A little more than half a mile from the village there was a fork in the road. As they approached it, the man said, "Young fella, run up there in front of 'em and turn 'em towards Listellick". He ran on ahead of the cattle and did as he was told, then dropped in behind them again. He had scarcely done so when the man said, "Young fella, run up there will you and stand in Dillons gate not to leave 'em in!" he ran past the cattle and stood in the gateway while they passed. As he fell in behind them again, he began to wonder how far they were to bring these animals. He was going to ask but somehow he didn't. Suddenly the man shouted, "Oh great God, there's a heifer gone into Mullins' field. Oh! the bloody gate was open. Oh! God blast it! Hop in there, boy bawn across the ditch and turn her out. I'll stop the rest of 'em. Good man yourself! Sure, you're a dinger!"

The boy climbed over the fence and went running towards the heifer. When she saw him coming, tired though she must have been, she took off at a fast trot away from him. He ran beyond her to turn her towards the gate. Just as he managed to get her turned, he saw two more of the cattle coming into the field. He heard the man shout, "Stop 'em! Stop 'em! Quick!Quick! Head 'em off!" The boy raced towards the animals. When they saw him coming they wheeled towards the gate, and he followed them until they were on the road. "Good man, Good man, yourself", the man said. "Now th'other one, run over like a good boy and bring her and we're right!" The boy looked around and saw the heifer munching ravenously fifty or sixty yards away. By now the hunger was attacking his own stomach pitilessly, and he was leg-weary and dispirited but he forced himself to run a little as he went towards the grazing animal. As he came near her, she glanced over her shoulder and began to trot away from him again. He forced his weary legs to dig into the ground in an effort to get beyond her. They had gone thirty yards before he managed to turn her . At last he got her on the road. By God, you're a great boy! Great entirely!" said the man. "Who would you be now?" The boy told him his name. " A son of the master's? inquired the man. "Yes" "Ah, you're a great boy! Great out! Sure we haven't that far more to go now" The boy, by now desperate with hunger and exhaustion, asked, "How far is it?" "Yerra, only up here a bit! I'll be alright when I get up as far as Paddy Stack's. I'll manage on my own after that. Sure I wouldn't be asking you at all only my bloody dog took poison th'other day and died on me . A great dog he was too". Paddy Stack's was almost a mile away, but despite everything the boy was determined to continue, he had come this far, he had got a job and the anticipation of going proudly in home with his earnings made it all seem worthwhile. They went on for a half a mile without incident. The man still shouted occasionally at the cattle, but even he seemed to have lost much of his enthusiasm and energy. When they reached the top of Fuller's Height the man said, "Run on ahead of 'em now, boy bawn. There's a bohriheen to your right up there and stand in it not to lave 'em up that way". The boy pushed himself past the animals and stood in the mouth of the lane-way. When they passed, he again joined the man behind them. They came to Paddy Stack's but the man said nothing and neither did the boy. Twice more he had to run ahead of the cattle to keep them from going off the road before the man said, "Listen, young fella, I'll manage from here myself. Do you know what I was thinking? I was thinkin' twas a pity you didn't walk in front of 'em instead of behind. You'd have spared us a lot of bother. But, then, you're not that used to cattle. Anyway, listen do you know who I am by any chance?" "No, I don't" said the boy. "Ah, well there you are! Listen, " he said putting his hand in his pocket and pulling out a fist of coins, "We'll have to pay you anyway, I suppose. Here you are now, a penny for yourself for sweets. Run on home now quick for we'll have rain, and 'twill be dark early". He pushed a penny into the boy's hand, shouted at the cattle and moved on up the road. The boy looked at the coin. A penny! A penny! after all that. Tears of anger and misery flooded his eyes. A penny! If it was a shilling itself! Sixpence even! How could he bring a penny in home! How could he! This was even worse than nothing. He began to run, half crying and complaining bitterly and loudly to himself as he ran. Without stopping, he flung the penny across the fence and after it the stick. They'd laugh when they heard, he knew they would; he could see them. He continued to run until he could run no more because of a stitch in his side. Then he walked a while and ran again, and walked and ran alternately until at last he reached his own gate. He walked slowly round the back of the house and opened the door. "Where in God's name were you until this hour?" they said. "Tis nearly dark. Were you working until now?" I brought cows with a man nearly to Listellick", he replied as he hung his coat and hat behind the kitchen door. "To Listellick?" they said unbelievingly. "Well, way past Paddy Stack's anyway". "Great God!" they said, "what kind of a man would drag a child that far!" "I don't know who he was". "Here", they said, "here sit near the fire. You must be exhausted. Here, here's your dinner. We kept it hot for you". He sat at the top of the table beside the fire. "Do you know what he gave me?" he said, his eyes filling again with tears, "A penny". Nobody laughed. They didn't laugh at all, but stood looking oddly at one another. His father, who had been reading the paper and appeared to be only half listening to the conversation, said "Bhuel anois, ta nios mo na sin tuillte agat, pe sceal e. Seo Dhuit". He came and put half-a-crown on the table beside the plate. Somebody brought in a lighted lamp. Somebody else went to draw the curtains. As they were being drawn the boy looked towards the window. Immediately outside a brilliant yellow light filled the garden. Beyond, towards Kilflynn, black clouds rode in tatters across a pale green sky. Soon the rain would begin to rattle on roofs and windows and sheds and would not stop until morning. |

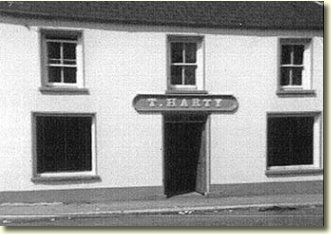

Nobody paid any attention to him so he walked more slowly back towards the Cross. He went through the Cross and east towards Shannow, stopping hopefully every now and then where only one man seemed to be in charge of a number of animals. He reached the edge of the fair in that direction. Still nobody paid any attention to him, so he turned and walked back the way he had come. He reached The Cross and saw one of the lads busily helping a man to keep seven or eight nervous cattle together near Tom Harty's pub. Then he saw another one helping to drive the cattle towards the railway station. He became conscious of the idle stick he was carrying and pushing his hand into his pocket, he held the stick half- hidden inside his arm.

Nobody paid any attention to him so he walked more slowly back towards the Cross. He went through the Cross and east towards Shannow, stopping hopefully every now and then where only one man seemed to be in charge of a number of animals. He reached the edge of the fair in that direction. Still nobody paid any attention to him, so he turned and walked back the way he had come. He reached The Cross and saw one of the lads busily helping a man to keep seven or eight nervous cattle together near Tom Harty's pub. Then he saw another one helping to drive the cattle towards the railway station. He became conscious of the idle stick he was carrying and pushing his hand into his pocket, he held the stick half- hidden inside his arm.