| Declan Gorman looks at the role theatre has played in the struggle for social change in history and more particularly in recent years in Ireland. He also offers advice and information on how to get involved in 'playing for change'. |

Theatre and Social Change

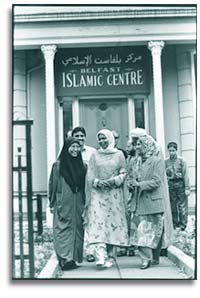

Racism against minority ethnic groups exists in Ireland as elsewhere. In particular it has been endured by the Traveller Community. The production of Charlie O'Neill's play, Rosie and Starwars by Calypso is one very positive action by artists, in dialogue with Travellers and Traveller organisations, to confront and educate people on the issues of racism and prejudice. The choice of subject matter and the manner in which it was researched typifies the issue-based theatre work Calypso has undertaken over the past five years. This, in turn, is located within a long standing tradition of arts practice, where the arts are seen - and theatre in particular - as a force for progressive change.

This web site and the information packs produced for the various shows concentrates not so much on art and anti-racism specifically, as on theatre as a progressive, humanising agent in society. Once it is accepted that theatre has a role to play in bettering and changing society, then the debate about its appropriateness or application to processes aimed at combating racial prejudice becomes simply a matter of how and when.

Ever

since actors first took to the boards, theatre has been used to highlight

the need for social change. But increasingly since the mid-nineteenth

century, theatre has been availed of by advocates of progressive reform

and indeed revolution. From opposition to the evils of colonialism through

to the modern movements against racism, homophobia, social exclusion etc.,

drama has proven a brilliant ally to radical, progressive movements. Ibsen's

play An Enemy of the People and Hauptmann's The Weavers were towering

works of European Naturalist Theatre which highlighted the corruption

and injustice at the end of the nineteenth century. The 1920's and '30's

in Europe and North America was a time of unprecedented social upheaval

and was marked by the emergence of dramatists such as Bertolt Brecht and

Clifford Odets who espoused left wing ideology and were opposed to the

capitalist systems of their day. In the '60's Peter Weiss with his Vietnam

Discourse and Peter Brook with U.S. combined stylistic innovation with

a powerful political message. In the '70's, the feminist movement developed

a theatre voice with, among others, Caryl Churchill's early plays.

Ever

since actors first took to the boards, theatre has been used to highlight

the need for social change. But increasingly since the mid-nineteenth

century, theatre has been availed of by advocates of progressive reform

and indeed revolution. From opposition to the evils of colonialism through

to the modern movements against racism, homophobia, social exclusion etc.,

drama has proven a brilliant ally to radical, progressive movements. Ibsen's

play An Enemy of the People and Hauptmann's The Weavers were towering

works of European Naturalist Theatre which highlighted the corruption

and injustice at the end of the nineteenth century. The 1920's and '30's

in Europe and North America was a time of unprecedented social upheaval

and was marked by the emergence of dramatists such as Bertolt Brecht and

Clifford Odets who espoused left wing ideology and were opposed to the

capitalist systems of their day. In the '60's Peter Weiss with his Vietnam

Discourse and Peter Brook with U.S. combined stylistic innovation with

a powerful political message. In the '70's, the feminist movement developed

a theatre voice with, among others, Caryl Churchill's early plays.

In Ireland, the National Theatre Society was closely linked to the emergence of a liberation movement in the early years of the century. More recently, in the 1950's, Brendan Behan's The Quare Fellow is said to have influenced the decision by the British Government to abolish hanging. In the 1970's Jim and Peter Sheridan pioneered a wave of modern Irish social realism in the Project Arts Centre, cultivating awareness and public outrage at the injustices of urban life with controversial plays on the burning issues of the day. In the '80's it was the turn of Passion Machine and Wet Paint with dramas set amongst the marginalised youth of Dublin. Co-Motion, meanwhile, explored international issues, presenting such work as Peter Weiss' anti-colonial play The Song of the White Man's Burden. By 1989 visual artists and theatre workers from all the main Irish companies were collaborating with advocates of social justice to mount the massive Parade of Innocence street theatre campaigns, highlighting miscarriages of justice.

This selective list of examples helps illustrate the tradition into which the work of Calypso Productions can be placed. There has, however, been one major development in recent years. Where once it fell to the altruistic or revolutionary visionary to mediate the experience which she or he observed, it is now very common to see community groups collectively creating and telling their own stories. This is taking the form of community arts projects, youth drama, art in development education and creative public demonstrations and protests.

The role of the campaigning artist has changed. The relationship between the politically awake artist and the community has become in many cases a collaborative, mutual learning one. Socio-political productions as exemplified by the current Calypso show are now part of the greater mosaic of story-telling and often involve extensive in-community consultation and research.

Community

art and the notion that artists might readily be found among the Traveller

community, refugees, illiterate people, prisoners, inner-city young people,

young farmers and other groupings outside a certain power-holding elite,

often elicits its own prejudiced reaction among those who control and

retain power and possession in the world of arts. And then there are also

those supposed purists who see art as a pursuit of excellence which only

'real artists' can attain. Such views, however, seem increasingly misplaced

these days when one views the natural alliances and commonality of purpose

which have developed between some of the most prominent artists in the

country and the communities in which they live.

Community

art and the notion that artists might readily be found among the Traveller

community, refugees, illiterate people, prisoners, inner-city young people,

young farmers and other groupings outside a certain power-holding elite,

often elicits its own prejudiced reaction among those who control and

retain power and possession in the world of arts. And then there are also

those supposed purists who see art as a pursuit of excellence which only

'real artists' can attain. Such views, however, seem increasingly misplaced

these days when one views the natural alliances and commonality of purpose

which have developed between some of the most prominent artists in the

country and the communities in which they live.

Furthermore, the notion of excellence has come under much scrutiny in recent times. Who defines it? How do you know you have witnessed or experienced it? And, after all, one of the most established norms of modern art is that there is no norm.

In fact, some of the greatest theatre experienced in Ireland in recent years has been presented in community halls by so-called non-artists, who arrived at crystals of truth that were temporarily as befits the theatre as important as the great moments of Irish stage genius recorded in the Abbey.

Another idea that the Guardians of Art in its Own Disconnected Float Chamber find controversial is the now widely held belief that not all art needs to be shared with a paying audience in order to live and be excellent. The very process of involvement in collective creative activity in workshops can alter individuals and communities and enable them to transform society. But is it art? I think so. I recently led a workshop with a mixed group of young people from Drogheda and five of Ireland's leading professional actors, based on Hauptmann's nineteenth century play about oppression of cottage weavers in famine-time Germany. The passion it evoked among the participants - not about that particular long-forgotten episode specifically, but about the propensity of humanity to exploit its weaker members - was remarkable. Perhaps one day we will develop this work in a full production. If not, it is already art in my head, art in their heads, art in the heads of a small number of people who looked on for part of the process. It is art because we dreamed ourselves anew and it is community art because it changed us collectively, just a little. Drama can create instant empathy. Once you empathise, you can no longer turn your back. Drama is essentially about this energy - it is a dynamic artform - and it sits comfortably with other means and methods and reasons for aspiring to change, to improve, such as education, community action, protest etc...

Groups, school teachers, campaigners and individuals concerned with arresting the rise of racism are increasingly looking to the arts as a means of communication and learning - the key to breaking down prejudice. The Cities Against Racism Project (under the auspices of the Irish Refugee Council) was a specific example. So too are the many projects undertaken in recent years by Pavee Point and the Irish Traveller Movement, alluded to in an excellent essay by Fran McVeigh in a book called A Heritage Ahead, (Pavee Point 1995). Comhlamh, the organisation of returned development workers runs courses that include a drama and media element and so on.

There is no right way or fixed way of using the arts in combating the dark forces in our society. All that is needed is the proverbial two planks and a passion. Nonetheless, there is a body of excellent practice which might one day be recorded in an alternative history: the Irish National Organisation of the Unemployed's hilarious street theatre piece called Juggling the Statistics (1992); the Gay Pride and Disability Pride Parades of recent years; the moving concert / performance in 1996 at the Temple Bar Music Centre to remember Ken Saro Wiwa and the Ogoni people, dying at the hands of the Nigerian government with the Shell Oil Corporation in the wings. The list is long.

So if you are concerned and want to make a difference, go for it! Get a group of people together. Contact C.A.F.E. or the National Association of Youth Drama (NAYD): Tel 01 - 8721938 regarding recommended lists of professional drama leaders in your area (they're not expensive to hire). Contact Pavee Point, the ITM, the Irish Refugee Trust (see addresses) or a similar reputable campaign organisation and ask for an introductory input from their information officer.

Then leave it up to the drama worker and the group to make magic and play for change.

South Great George's St.

Dublin 2, Ireland

T (353 1) 6704539

F (353 1) 6704275

calypso@tinet.ie

— Welcome -

About - Productions - Funding

- Theatre and Social Change -

— Racism - Refugees and Asylum

Seekers - Prisons -

![]()