In October 2002 the Northern Ireland power-sharing government collapsed following the discovery by security forces of an alleged IRA/Sinn Féin spying operation at Stormont, the so-called 'Stormontgate' affair. In return for an end to the IRA military campaign, Sinn Féin had been admitted to participation in government, and it was hoped that the era of political violence was coming to an end. The most prominent member of Sinn Féin arrested in 2002 was Denis Donaldson, the party's principal administrator at Stormont, in whose home a cache of incriminating documents was found by police. On 8 December 2005 charges against Donaldson and two co-accused were dropped on the grounds that prosecution was 'no longer in the public interest', an interesting phrase which was interpreted as meaning that an 'intelligence resource' was the actual object of protection. Just over a week later it was revealed that Donaldson had been a long-serving spy for the British, and it was clear that he had in fact been 'outed' and abandoned by his former handlers. (1) Having been debriefed by his former Republican colleagues, Donaldson apparently felt secure enough to go and live in an isolated cottage near Glenties, County Donegal. On 4 April 2006 Donaldson was found shot dead in his cottage, at a time when renewed efforts were being made to restore a power-sharing government in Northern Ireland. Republican sources indicated that Donaldson's killers were probably security agents eliminating a man who knew too much, while security sources for their part stated that he was assassinated by dissident Republicans seeking revenge for his betrayal of comrades. Whoever killed Donaldson, it is clear that he had been employed to serve a murky purpose one last time, and his secrets are now secure in the grave.

Was Molloy Childers a British Spy?

A book published in 2006 on the intelligence war 1919-21 between the British and Michael Collins's IRA, by scholar Michael T Foy, features a claim that Molly Childers, wife of the Irish Republican leader, Erskine Childers, was in fact a British spy. (3) Coming hard on the heels of the recent Donaldson revelations (see above), the claim seemed not entirely implausible, and aside from a denial from the Childers family, it has not been generally challenged. Molly Osgood Childers belonged to a leading Boston family, and married Erskine Childers before his conversion from Unionism to the cause of Irish independence. Childers took the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War which followed the Anglo-Irish agreement of 1921, and he was himself accused unjustly of being a British spy by former comrades on the pro-Treaty side. Captured in possession of a gun presented to him by Michael Collins, Childers was court martialled and executed by the new Irish government in 1922, in what was a clear case of judicial tit-for-tat killing. The claim that Childers's wife was a spy is therefore quite sensational, but of course speculative. Foy is quoted as stating that the mysterious spy had access to top Sinn Féin leaders, used 'American-sounding turns of phrase', and that throughout her life Molly 'displayed intelligence, courage, decisiveness and single-minded determination'. The question arises as to why such a woman would choose to betray all that her husband had come to hold dear. The spy refers in reports to someone called 'Bob', who Foy suggests could have been Molly's husband, his full name being Robert Erskine Childers. This again begs the question as to how someone seeking to avoid detection would risk recording a name of someone so close to her. Furthermore, Foy does not itemise any really high-grade intelligence provided by his spy, and she appears to have been one of those know-all operatives, more inclined to tell her handlers how to fight the war than to provide reliable information. Examples of the spy's style include an implausible claim that Eamon de Valera was 'a red-hot extremist' who wished to have King George V assassinated, and the plainly misinformed advice that peace negotiations with the rebels were a waste of time. (4) After her husband's death, Molly Childers remained the keeper of his memory and a supporter of the Irish national cause, and in short the claim that she was a British spy seems to be a very unlikely one.

The Hunt Museum and Nazi Connections

The Hunt Museum in Limerick holds a compact collection of artefacts and artworks donated to the Irish people by the late John and Gertrude Hunt, who were prominent dealers and collectors. In 2003 it was alleged that the provenance of some of the material in the museum was suspect and that the Hunts had links with Nazis and dealers in material looted during World War II. These allegations were taken up by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, which demanded a full enquiry by the Irish government. The Hunt Museum denied the allegations, but moved to allay concerns by placing a catalogue of its holdings on its website. After a false start when one investigating group folded due to funding problems, in 2005 the Irish government funded an enquiry to be held under the auspices of the Royal Irish Academy. This group was headed by retired civil servant Seán Cromien, and its report was issued in June 2006. (5) Acknowledging gaps in provenance records, the group referred to loss of documents during World War II, and concluded that 'it is probable that most of the objects with gaps do not have problematic pasts'. (6) Because of his research on Joyce manuscripts with similar provenance problems, it seemed to the present writer that the group was being rather optimistic in its conclusion, and had not dug deeply enough. The impression of a whitewash if not a cover-up of the Hunt Museums's unpleasant associations has been confirmed by the revelation that there exists in the Irish military archives a file detailing a close personal and business relationship between John Hunt and Count Alexander von Frey, who had links with Hermann Göring, and recorded as well are Hunt's connections with two traffickers in looted art, Arthur Goldsmith and Emil Buhrle (though it is claimed that the last is a misidentification). (7) All state cultural institutions should have an obligation to check thoroughly and proactively the provenance of material they acquire through purchase or donation. An unfortunate aspect of the Hunt Museum affair is the apparent 'targeting' of the individual who first revealed the possibility of problems with the collection, and indeed the present writer is well familiar with the negative responses of officials whose judgement in such matters is called in question.

Annie Moore

Annie Moore's fame rests on the fact that as a fifteen-year old girl she was the first immigrant to enter Ellis Island in New York in January 1892. She is commemorated by statues sculpted by Jeanne Rynhart at both Ellis Island and Cobh in Ireland from where she sailed. It was obviously a matter of interest to know the details of Annie's life after her arrival in the United States, and she had hitherto confidently been identified as a person of the name who had moved west and ultimately died in an accident in Texas in the 1920s. For genealogist Megan S Smolenyak there was something not quite right about the story, and she set about examining the documentation, also seeking the assistance of other genealogists through the expedient of offering a €1,000 reward for information. The result was that in September 2006 it was revealed that the real Annie Moore had now been identified, that she had in fact stayed in New York, married there, had children and died of heart failure aged 47 in 1924. Annie was buried in an unmarked grave in Calvary Cemetery, and there are plans to erect a memorial to her. (8) As demonstrated in our piece on Molly Malone, it is probably a prudent thing to hire a competent genealogist to do background research before calling in the sculptor!

John Condon, Boy Soldier

The story of John Condon, allegedly the youngest soldier to die in WWI aged 14, has been the subject of much media attention in recent years, and there are plans to erect a statue to him in Waterford. (9) His grave is said to be the most visited in Flanders. However, there are serious questions concerning the accuracy of this tale. A webpage at http://www.cwgc.co.uk/Condonevidence.htm supplies exhaustive documentary evidence to show that John Condon was in fact aged 18 when killed in action on 24 May 1915. In particular, a copy of John Condons's birth record is included, showing that he was born on 16 October 1896 in Waterford. More than that, it is claimed that Condon is not in fact buried in the grave in Flanders, but one Patrick Fitzsimmons of Belfast. As with Molly Malone and Annie Moore, it would appear that a statue may be erected to perpetuate a myth rather than historical truth.

Turkish Aid to Ireland During the Great Famine

In March 2010 President Mary McAleese sparked some debate during a visit to Turkey by claiming in a speech that Sultan Abdul Majid had sent three ship-loads of food to Drogheda during the Great Famine in the 1840s. Furthermore, claimed the President, since that time the coat of arms of Drogheda featured the star and crescent to commemorate Turkey's kindness. (10) It was soon pointed out that there was no record of such aid being received in Drogheda and that the town's arms were ancient, so that it appears that the President's speech was based on a garbled local legend. However, it later emerged that there was at least a grain of truth in what the President had to say, in that a document was exhibited in the European Commission Office in Dublin in June 2010, which was a letter signed by members of the gentry thanking the Ottoman Sultan for generously donating £1,000 to the Irish people in 1847. (11) The Drogheda tale can be traced back via Wikipedia and various Internet incarnations to quotations from the memoirs of Taner Baytok, a former Turkish ambassador to Ireland, and it is claimed that in 1995 the mayor of the town, Alderman Frank Godfrey, 'paid honor to Baytok and erected a plaque in the Westcourt Hotel, which was then the City Hall where Turkish seamen stayed'. Baytok is also reported as citing an article by the historian Thomas P O’Neill in a magazine called The Threshold in 1957, which it would be interesting to locate. (12) There is a need for further research to establish the full truth concerning Turkish aid to Ireland during the Famine, which indeed does point to the potential for good Christian-Islamic relations, but this research will need to go a little beyond copying and pasting uncritically from sources such as Wikipedia.

Was Kennedy's 1963 Dáil Speech Censored?

Irish media personality Ryan Tubridy has written a book, tied in with a television programme, dealing with US President John Fitzgerald Kennedy's visit to Ireland in June 1963, just five months before he was to die by an assassin's bullet in Dallas. (13) It was a remarkably successful visit, during which Kennedy established a special relationship with Ireland unequalled until the time of his successor, Bill Clinton. There was, however, one reportedly slightly jarring note during Kennedy's trip, in the form of an attempted joke which allegedly fell rather flat. On 28 June 1963, Kennedy was addressing the two houses of the Irish legislature, the Dáil and Seanad, in Leinster House, Dublin, the former city residence of the Fitzgeralds, Dukes of Leinster. Whether it was his own devilment, or more likely that of his speechwriter Ted Sorensen, Kennedy quoted from a letter written by a former resident, the 1798 revolutionary Lord Edward Fitzgerald, who had noted that 'Leinster House does not inspire the brightest ideas'. The joke might seem less than funny to us in the wake of the collapse of the 'Celtic Tiger', perhaps because of the terrible truth it enshrines, and it is little ameliorated by Kennedy's rider, 'That was a long time ago, however'. According to Tubridy, 'there was some murmuring and shifting in the seats', and citing recollections of Taoiseach Seán Lemass, President Eamon de Valera was said to have rebuked Kennedy later in the day, stating that 'he had done no service to Irish politicians by this quotation'. More than that, Tubridy quotes Lemass as claiming that de Valera saw to it that the offending comment 'disappeared completely', so that it did not appear 'in any of the records of the speech that have been published', or even in the tape and film records of the speech. (14)

Here are copies of the relevant paragraph of Kennedy's speech to the Dáil and Seanad, respectively from the JFK Library and the Irish legislature's records, both now conveniently available online:

http://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/Archives/JFKPOF-045-036.aspx, page 2, first paragraph

http://www.oireachtas.ie/viewdoc.asp?UserLang=GA&fn=/documents/addresses/28Jun1963.htm

It can be seen that the offending joke about Leinster House is in place, unexpunged, uncensored in the official published record of the Irish legislature. Stranger to relate, the paper of record, the Irish Times, reported that Kennedy's first humorous comment got a 'hearty laugh', but that 'the laughter was even louder' when the President quoted Lord Edward as above, indicating that the assembled TDs and Senators could in fact take a joke against themselves. (15) The story that the most powerful man in the world had died on stage and indeed had even been censored in the land of his ancestors undoubtedly made good journalistic copy, and has now found a berth in Wikipedia and other places online. History is an exacting discipline whose practicioners need to keep critical faculties on full alert and, above all, to take the time and trouble to check relevant records before giving credence to colourful yarns which may have little or no basis in fact.

Wikiplagiarism

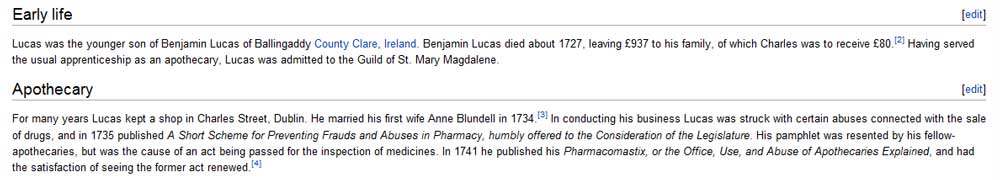

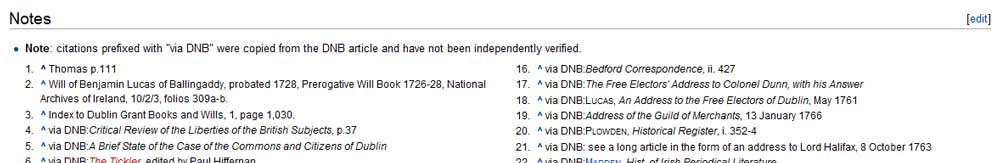

There is no doubt that the Internet is a marvellous method of spreading information throughout the world, opening up unknown or complex subjects hitherto the preserve of experts and scholars. Yet we know only too well that the Internet is also a wonderful means of spreading misinformation. There is another unattractive habit which has been greatly encouraged by the copy and paste-friendly environment of webpages, namely, plagiarism, that is, the presentation of verbatim or near-verbatim transcripts of the words of another without acknowledgement of the source and as though they were one's own composition. Wikipedia may be useful for casual reference purposes, but as students are warned, the free online encyclopedia's mix of information and misinformation means that it cannot be safely relied upon and should not generally be cited in assignments. Wikipedia alas may be adding plagiarism to its existing problems, as I will demonstrate in relation to some of my own online work on the eighteenth-century Irish patriot Charles Lucas. Wikipedia's article on Lucas is composed in the main of a verbatim transcription of an article in the old and presumably out of copyright Dictionary of National Biography, an unsatisfactory approach but one which cannot be called plagiarism in that there is a candid acknowledgement that this is being done. (16) However, some additional text has been added to the Wikipedia article in such as way as to indicate that it is based on the author/editor's own research, as can be seen from the following screen prints:

A comparison can be made with the following extracts from my online booklet on Lucas (17):

relatively generous total of £937 to his wife Mary and large family, . . . . . Charles, the second youngest son, was allocated £80 . . . . .4 . . . . . Lucas married his first wife Anne Blundell in 1734.9

4 Will of Benjamin Lucas of Ballingaddy, probated 1728, Prerogative Will Book 1726-28, National Archives of Ireland, 10/2/3, folios 309a-b.

. . . . .

9 Index to Dublin Grant Books and Wills, 1, page 1,030.

In the process of copying my work the author/editor of the Wikipedia article did make some textual alterations, for example, 'Benjamin Lucas died about 1727, bequeathing . . .' changed to 'Benjamin Lucas died about 1727, leaving . . .'. However, the author then went on to reproduce verbatim the text of two of my footnotes as indicated above. This is what is known as 'sources plagiarism', and if it is wrong to use words and phrases of another author without acknowledgement, then it is even more unethical to present sources cited by another as though one had searched them out oneself.

At this point some readers may be reacting with impatience, perhaps thinking that this kind of thing is done all the time and that most students, authors and indeed journalists steal freely in order to get work done. I do not believe that this is entirely true, but would have to acknowledge that the practice of plagiarism is growing, helped by the easy reproducibility of online text. Plagiarism of work which has itself been plagiarised can now be encountered as well, so that a Google search will sometimes show chunks of text in a suspect work appearing on multiple websites, with the original source identifiable only with a considerable amount of effort. Indeed, it is probably only a matter of time before genuine authors are accused of plagiarising sources like Wikipedia, on the grounds that portions of their writings can be found there, which is why the present writer is putting down a marker. Wikipedia is aware of the problem of plagiarism in its web content, but adopts a non-blame approach which could be interpreted as quasi-tolerance, noting that 'most articles are written by people with no specialist training in the topic, and with no academic or professional background in writing, editing, or researching', so that plagiarism 'is therefore something that can easily happen inadvertently on Wikipedia'. (18) Of course the standard defence to a charge of plagiarism is that it was unintentional, and the problem is indeed probably due as much to laziness as to poor scholarly ethics. Some practical advice for all writers: ensure that most of what you write is in your own words, always give credit to other authors who have provided key information and where you quote verbatim, place the text in inverted commas and cite your source in the form author, title, place and date of publication (publisher as well if you wish), giving page reference(s) and URL if published online.

Genetically Modified Pedigrees

The mapping of the human genome is undoubtedly one of the great advances in scientific discovery, promising many benefits for humankind, particularly in the area of health. DNA analysis is increasingly important in genealogy also, leading to the new term 'genetic genealogy'. When the paper trail has run cold, so the most enthusiastic advocates claim, analysis of DNA can enable researchers to continue tracing their ancestors back into antiquity. In particular, those who hitherto had ordinary lineages running back only a few centuries can now pride themselves on being descended from the likes of Genghis Khan or Niall of the Nine Hostages, acquiring in the process what might be called 'genetically modified pedigrees'.

News in 2003 that 0.5 per cent of the world's male population could be descended from Genghis (19) was followed in 2006 by the revelation that a study by Trinity College Dublin geneticists had suggested that about 3 million men around the world may be descended from Niall. (20) A Google search shows how both stories rapidly entered Internet mythology with only a few voicing caution or scepticism. While Genghis was a real twelfth-century warlord, Niall was a quasi-mythological fifth-century Irish monarch. In both cases it is not at all clear how geneticists could claim to have verified the actual identities of their subjects' common ancestors. One genetic testing firm even for a time issued certificates of descent from Niall of the Nine Hostages!

Genetics is a complex science, history being apparently less complicated and indeed not usually dignified with the title 'science'. However, as a trained historian, the writer confesses that he is appalled by the poor understanding of historical methodology and rules of evidence displayed by some genetic scientists who venture into the field of family history. Whatever about the claim that DNA analysis had established that Scottish comedian Fred Macaulay's lineage was not Viking but southern Irish, it seems absurd to speculate that his 'ancestor was a slave, sold to a sea-lord with the name of Olaf at the great Dublin slave-market some time in the 9th or 10th centuries'. (21) If the DNA analysis is correct, it would be more likely that Fred could be descended from an emigrant bearing the Irish surname MacAuley or even MacAuliffe which became assimilated to the Scottish Macaulay, these names having similar Gaelic origins. Genetic genealogy can be expensive, with DNA tests costing hundreds of Euros, and indeed the American Society of Human Genetics cautioned in 2008 that those who 'undergo ancestry testing often do not realize that the tests are probabilistic and can reach incorrect conclusions'. (22) While acknowledging the potential usefulness of DNA analysis to genealogists, the writer's advice would be not to neglect documentary research and to proceed with the genetic option only if one has the necessary funds and an awareness of its limitations.

Montgomery and Abbeville

In May 2013 the Irish Times announced in connection with the sale of Charles J Haughey's former grand residence, Abbeville, County Dublin, that historical research company Eneclann had discovered the late Taoiseach was not the only 'figure of political interest' to be associated with the estate. According to the newspaper, 'revelatory research' commissioned by estate agents Sherry Fitzgerald showed that General Richard Montgomery, an heroic figure of the American War of Independence who was slain at Quebec in 1775, 'was reared on the estate'. (23)

This rang a bell, and a quick Google search showed that back in December 2002 historian Eugene A Coyle had publicised the connection between Abbeville and Montgomery, whose Irish associations had until then been little studied. Coyle gave a presentation to the Rush Historical Society showing, according to a contemporary newspaper account, that the 'Haughey demesne stands on the spot where Montgomery was born in December 1738'. (24) In 2001 Coyle also published an interesting article on Montgomery, significantly titled 'From Abbyville to Quebec', which is now freely available online. (25) It may be considered eccentric to say so, but this prior research should have been acknowledged. I took it upon myself to draw the matter to the attention of Eneclann on 21 May 2013, but they claimed to be unaware of the earlier research. A single reference to Coyle's article now appears in an online history of Abbeville compiled by Eneclann in relation to the sale of the estate by Sherry Fitzgerald, although in my opinion the weight of the article would have required more prominent acknowledgement. (26) Eneclann certainly fleshed out the details of Montgomery's connection with Abbeville, but the company by no means discovered the fact.