Home

View

Guileen

Photos

20th Century

19th Century

Guileen S.A.C fixtures

Fishing &

Bait

Anglers and Catch

Anglers and Species

History of the Guileen Arms

Guileen Tackle Shop

A

Gem of Guileen

A Trip Down

Memory Lane

Residents past and present

Poem's and Song's

Ship wrecks

Video gallery

Links

View

Guestbook

Sign

Guestbook

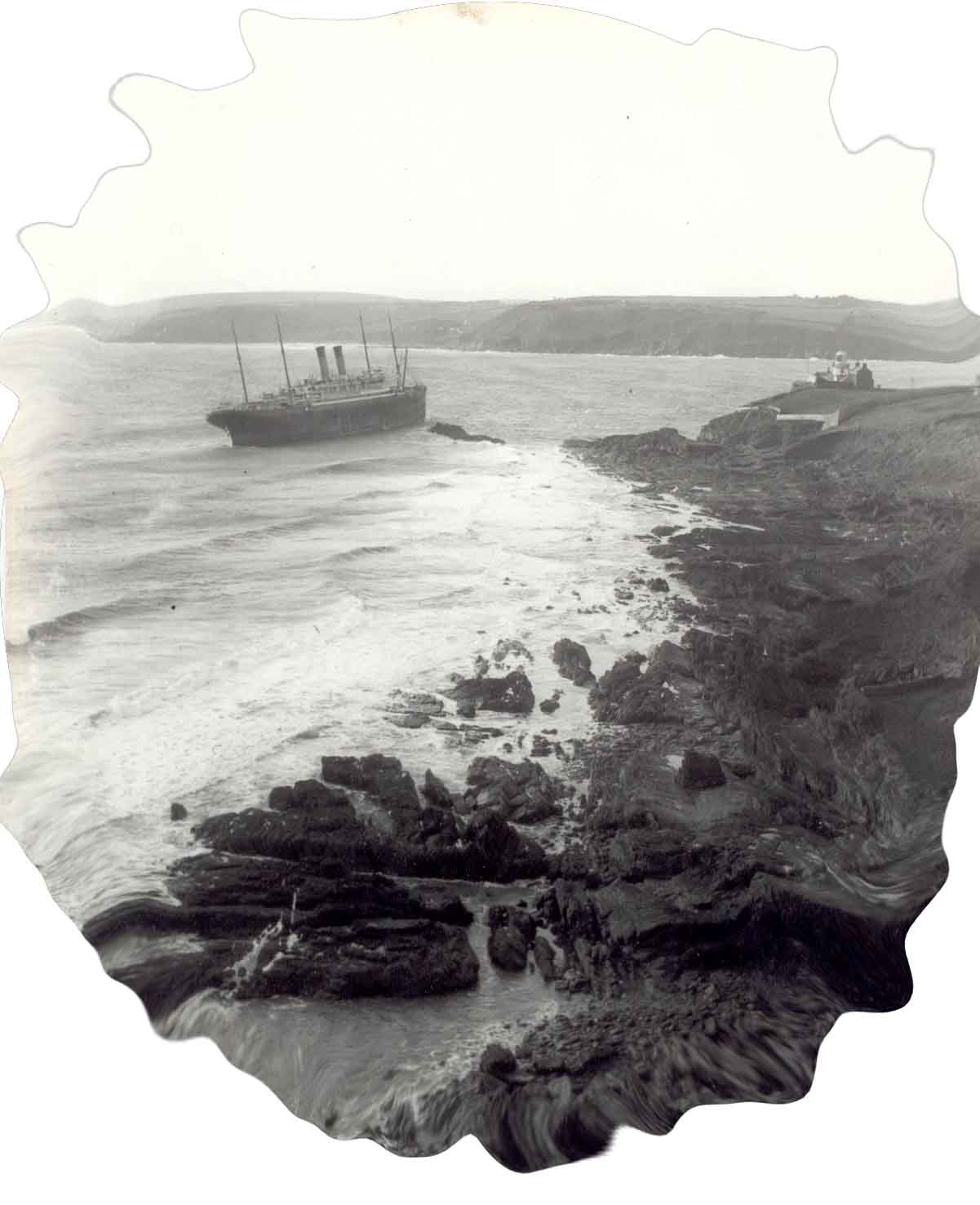

Drama at Roches Point 50 years ago

By

Barry Collins

Fifty years ago, on December 10, 1928, the great transatlantic liner, Celtic, ran aground near Roches Point, at the entrance to cork Harbour, and became a total loss. The Celtic was a luxury liner plying the Liverpool/Cobh/New York run.

On board were more than 500 people and a cargo of grain and fruit for the Christmas market. The stranding of the liner is firmly established in the folklore of the harbour area, and every Christmas memories of the event - particularly the salvaging of the cargo - are recalled and embellished.<

The Celtic had an amazing history. Launched in 1901 for the white Star line, she was the largest ship in the world at the time of her construction. Commandeered by the British Admiralty in 1914, she was converted into an armed cruiser. In 1916 she became a troop ship and a year later hit a mine and was badly damaged. Back in service, she was torpedoed in the Irish sea.

After the war the Celtic collided with a coaster in 1925 and two years later crashed into another ship. Finally, in 1928 she went on the rocks in controversial circumstances at Roches Point. It took five years to dismantle the vessel and as recently as two summers ago skin divers were still collecting bits and pieces of her.

Salvaging the wreck provided work for 50 Cobh men. The contractors were the Dover firm of A.O. Hill in partnership with Copenhagen firm of Peterson and Albeck. Mr. Hill wanted to refloat the Celtic and tow the vessel to Haulbowline Dockyard to be scrapped but the cork harbour board opposed the plan, on the grounds of danger to the harbour channel being blocked. The liner was dismantled on the spot. It is worth noting that the operation. Which was completed in 1933, eventually resulted in the formation of Haulbowline Industries Ltd. whose scrap yard was later set up in passage west.

Apples invasion

The ordinary people of Cobh also benefited from the wreck. Part of the cargo was made up of apples that floated in, in there thousands to the town. Like manna from heaven, they were collected at the shore. Some were sold in shops as "Celtic Apples" a penny each", at an unreserved Salvage Auction" of the ships fittings, local men bought some of the lifeboats at a very reasonable price. They brought the boats into Cobh and celebrated their good fortune in a Public house. A storm blew up and wrecked the boats. When the men left the pub and saw their smashed boats they realized that the "ill star" that had followed the liner had also cursed their purchases

Another man who had "salvaged" the purser's pet linnet boasted of having the most travelled bird in the world. He had argued that the bird had clocked up thousands of miles on the Liverpool/New York journey. The linnet, which was the wonder of the local hostelries, eventually died of exhaustion .

A crate load of shoes also "floated" ashore, but to the disappointment of its finders, fitted only the left foot. The create for the foot, that would have matched the shoes ashore, was never discovered.

People living at Roches Point soon tired of having a liner on there door step when the rats from the ship began invading there dwellings.

TRAGEDY

As well as bringing work to Cobh, the ship also brought tragedy. On November 30, 1929, four work men where poisoned by toxic gas generated in a hold containing maize. The first to die was Jeremiah Burke who had gone down into the hold to repair a leak in a pump. John Wilmot and Michael Carmichael tried to save him but died in the attempt. A fourth man, John Finley, was rescued in an unconscious state and subsequently died in Cobh Hospital. Their bravery is still remembered in Cobh. Thousands attended the burial of the four victims and, it is said, during the funeral the keening of the dead was heard for the last time in the town.

A curious aspect of the stranding of the ship is that the British Board of Trade never held an inquiry. The findings of the private inquiry held by White Star Line were never published. Never the less, the owners of the Celtic did not do to badly out of the accident. The vessel was insured for £230,000. Most of the cargo valued at £160,00 was salvaged. Since the ship had seen 27 years of service, the owners considered it to old to be worth repairing. Such facts led to accusations that the Celtic had been deliberately stranded but no evidence of this was ever produced. Conflicting reports exist, however, as to the manner in which the Celtic ran aground. On the night of December 8, 1928, the master sent a radio message to Liverpool stating that he was bypassing Queenstown (Cobh) and going on to liver pool. The pilots in Cobh considered he had made a wise decision in view of the heavy sea and bad winds. Early in the morning of the 10th the vessel was passing the Daunt Lightship and was off Ballycotton then, inexplicably, it turned and made back for Cork Harbour. The special pilot of the Whit Star Line who operated out of Cobh in a whaleboat. Just in side the mouth of the Harbour, the vessel stopped and appeared to be backing out. This resulted in the stern of the vessel being thrown to the southeast and eventually being driven onto the rocks at Roches Point.

NO PANIC

Once the wind moderated a tender, the Morsecock, was able to get alongside and take off all the passengers and crew. There was no panic on board. After the first excitement had died down, the passengers went back to bed. They had a hearty breakfast before boarding the tender. Ironically the liner, was carrying passengers who where passengers of another shipwreck Vessels, the Vestris.

Mr. Donovan, the pilot of the White Star Line pilot boat, reported that he signalled to the liner and was answered. He became alarmed when he saw the liner getting closer to the shore and obviously going off course. He was of the opinion that the cause of the accident was a heavy southwest sea and might have been avoided if the captain had kept the ship more to the west.

The Celticís master Captain G. Berry, in his testimony made know mention of the ship changing course form Liverpool nor did he mention reversing his decision and making for Cobh. Form his sworn statement, it would appear Capt. Berry blamed the weather and the pilot. The cause of the accident he said was due to the strong winds and the heavy sea, and the elements had reduced the grandeur of the ship to a rusting heap of scrap. When the work men where dismantling the vessel they came across pieces of iron embedded in her keel plates - remains of another liner the Chicago, wrecked in the same spot in January 1868.

___________________________________________

Do not change subject line used for filtering spam

© 2001-2007John

McCormack

Web Design by Janine

McKeon

Free Web Counters & Statistics |